Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

BILLING CODE: 4510-27-P

DEPARTMENT OF LABOR

Wage and Hour Division

29 CFR Part 541

RIN 1235-AA39

Defining and Delimiting the Exemptions for Executive, Administrative, Professional,

Outside Sales, and Computer Employees

AGENCY: Wage and Hour Division, Department of Labor.

ACTION: Final rule.

SUMMARY: The Department of Labor (Department) is updating and revising the regulations

issued under the Fair Labor Standards Act implementing the exemptions from minimum wage

and overtime pay requirements for executive, administrative, professional, outside sales, and

computer employees. Significant revisions include increasing the standard salary level,

increasing the highly compensated employee total annual compensation threshold, and adding to

the regulations a mechanism that will allow for the timely and efficient updating of the salary

and compensation thresholds, including an initial update on July 1, 2024, to reflect earnings

growth. The Department is not finalizing in this rule its proposal to apply the standard salary

level to the U.S. territories subject to the Federal minimum wage and to update the special salary

levels for American Samoa and the motion picture industry.

DATES: The effective date for this final rule is July 1, 2024. Sections 541.600(a)(2) and

541.601(a)(2) are applicable beginning January 1, 2025.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Daniel Navarrete, Acting Director, Division

of Regulations, Legislation, and Interpretation, Wage and Hour Division, U.S. Department of

Labor, Room S-3502, 200 Constitution Avenue, NW, Washington, DC 20210; telephone: (202)

693-0406 (this is not a toll-free number). Alternative formats are available upon request by

calling 1-866-487-9243. If you are deaf, hard of hearing, or have a speech disability, please dial

7-1-1 to access telecommunications relay services.

Questions of interpretation or enforcement of the agency’s existing regulations may be

directed to the nearest Wage and Hour Division (WHD) district office. Locate the nearest office

by calling the WHD’s toll-free help line at (866) 4US–WAGE ((866) 487-9243) between 8 a.m.

and 5 p.m. in your local time zone, or log onto WHD’s website at

https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/contact/local-offices for a nationwide listing of WHD district

and area offices.

SUPPLEMENTARY INFORMATION

I. Executive Summary

The Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA or Act) requires covered employers to pay

employees a minimum wage and, for employees who work more than 40 hours in a week,

overtime premium pay of at least 1.5 times the employee’s regular rate of pay. Section 13(a)(1)

of the FLSA, which was included in the original Act in 1938, exempts from the minimum wage

and overtime pay requirements “any employee employed in a bona fide executive,

administrative, or professional capacity[.]”

1

The exemption is commonly referred to as the

“white-collar” or executive, administrative, or professional (EAP) exemption. The statute

1

29 U.S.C. 213(a)(1).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

expressly gives the Secretary of Labor (Secretary) authority to define and delimit the terms of the

exemption. Since 1940, the regulations implementing the EAP exemption have generally

required that each of the following three tests must be met: (1) the employee must be paid a

predetermined and fixed salary that is not subject to reduction because of variations in the quality

or quantity of work performed (the salary basis test); (2) the amount of salary paid must meet a

minimum specified amount (the salary level test); and (3) the employee’s job duties must

primarily involve executive, administrative, or professional duties as defined by the regulations

(the duties test). The employer bears the burden of establishing the applicability of the

exemption.

2

Job titles and job descriptions do not determine EAP exemption status, nor does

merely paying an employee a salary.

Consistent with its broad authority under the Act, in this final rule the Department is

setting compensation thresholds for the standard test and the highly compensated employee test

that will work effectively with the respective duties tests to better identify who is employed in a

bona fide EAP capacity for purposes of determining exemption status under the Act.

Specifically, the Department is setting the standard salary level at the 35th percentile of weekly

earnings of full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region ($1,128 per week or

$58,656 annually for a full-year worker)

3

and the highly compensated employee total annual

2

See, e.g., Idaho Sheet Metal Works, Inc. v. Wirtz, 383 U.S. 190, 209 (1966); Walling v. Gen.

Indus. Co., 330 U.S. 545, 547-48 (1947).

3

In determining earnings percentiles in its part 541 rulemakings since 2004, the Department has

consistently looked at nonhourly earnings for full-time workers from the Current Population

Survey (CPS) Merged Outgoing Rotation Group (MORG) data collected by the U.S. Bureau of

Labor Statistics (BLS). As explained in section VII.B.5.i, the Department considers data

representing compensation paid to nonhourly workers to be an appropriate proxy for

compensation paid to salaried workers, although for simplicity the Department uses the terms

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

compensation threshold at the annualized weekly earnings of the 85th percentile of full-time

salaried workers nationally ($151,164). These compensation thresholds are firmly grounded in

the authority that the FLSA grants to the Secretary to define and delimit the EAP exemption, a

power the Secretary has exercised for 85 years.

The increase in the standard salary level to the 35th percentile of weekly earnings of full-

time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region better fulfills the Department’s

obligation under the statute to define and delimit who is employed in a bona fide EAP capacity.

Upon reflection, the Department has determined that its rulemakings over the past 20 years, since

the Department simplified the test for the EAP exemption in 2004 by replacing the historic two-

test system for determining exemption status with the single standard test, have vacillated

between two distinct approaches: One used in rules in 2004

4

and 2019,

5

that exempted lower-

paid workers who historically had been entitled to overtime because they did not meet the more

detailed duties requirements of the test that was in place from 1949 to 2004; and one used in a

rule in 2016,

6

that restored overtime protection to lower-paid white-collar workers who

performed significant amounts of nonexempt work but also removed from the exemption other

lower-paid workers who historically were exempt because they met the prior more detailed

salaried and nonhourly interchangeably in this rule. The Department relied on CPS MORG data

for calendar year 2022 to develop the NPRM, including to determine the proposed salary level.

The Department is using the most recent full-year data available for this final rule, which is CPS

MORG data for calendar year 2023. The new standard salary level of $1,128 per week is $12 to

$30 less than the Department estimated in the NPRM. 88 FR 62152, 62152–53 n.3 (Sept. 8,

2023).

4

69 FR 22122 (April 23, 2004).

5

84 FR 51230 (Sept. 27, 2019).

6

81 FR 32391 (May 23, 2016).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

duties test, an approach that received unfavorable treatment in litigation.

7

Having grappled with

these different approaches to setting the standard salary level, this final rule retains the simplified

standard test, the benefits of which were recognized in the Department’s 2004, 2016, and 2019

rulemakings,

8

while, through a revised methodology, fully restoring the salary level’s screening

function and accounting for the switch from a two-test to a one-test system for defining the EAP

exemption, and also separately updating the standard salary level to account for earnings growth

since the 2019 rule.

The new standard salary level will, in combination with the standard duties test, better

define and delimit which employees are employed in a bona fide EAP capacity. By setting a

salary level above what the methodology used in 2004 and 2019 would produce using current

data, the new standard salary level will ensure that, consistent with the Department’s historical

approach to the exemption, fewer lower-paid white-collar employees who perform significant

amounts of nonexempt work are included in the exemption. At the same time, by setting the

salary level below what the methodology used in 2016 would produce using current data, the

new standard salary level will allow employers to continue to use the exemption for many lower-

paid white-collar employees who were made exempt under the 2004 standard duties test. The

combined result will be a more effective test for determining who is employed in a bona fide

EAP capacity. The applicability date of the new standard salary level will be January 1, 2025.

The Department is not finalizing its proposal to apply the standard salary level to the U.S.

7

The Department never enforced the 2016 rule because it was invalidated by the U.S. District

Court for the Eastern District of Texas. See Nevada v. U.S. Department of Labor, 275 F.Supp.3d

795 (E.D. Tex. 2017).

8

See 84 FR 51243–45; 81 FR 32414, 32444–45; 69 FR 22126–28.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

territories subject to the federal minimum wage and to update the special salary levels for

American Samoa and the motion picture industry.

9

The Department is also increasing the earnings threshold for the highly compensated

employee (HCE) exemption, which was added to the regulations in 2004 and applies to certain

highly compensated employees and combines a much higher annual compensation requirement

with a minimal duties test. The HCE test’s primary purpose is to serve as a streamlined

alternative for very highly compensated employees because a very high level of compensation is

a strong indicator of an employee’s exempt status, thus eliminating the need for a detailed duties

analysis.

10

The Department is increasing the HCE total annual compensation threshold to the

annualized weekly earnings amount of the 85th percentile of full-time salaried workers

nationally ($151,164). The new HCE threshold is high enough to reserve the test for those

employees who are “at the very top of [the] economic ladder”

11

and will guard against the

unintended exemption of workers who are not bona fide EAP employees, including those in

high-income regions and industries. The applicability date of the new HCE total annual

compensation threshold will be January 1, 2025.

In each of its part 541 rulemakings since 2004, the Department recognized the need to

regularly update the earnings thresholds to ensure that they remain effective in helping

9

The Department proposed in sections IV.B.1 and B.2 of the NPRM to apply the updated

standard salary level to the four U.S. territories that are subject to the federal minimum wage—

Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana

Islands (CNMI)—and to update the special salary levels for American Samoa and the motion

picture industry in relation to the new standard salary level. The Department will address these

aspects of its proposal in a future final rule.

10

See 69 FR 22172–73.

11

Id. at 22174.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

differentiate between exempt and nonexempt employees. As the Department observed in these

rulemakings, even a well-calibrated salary level that is not kept up to date becomes obsolete as

wages for nonexempt workers increase over time.

12

Long intervals between rulemakings have

resulted in eroded earnings thresholds based on outdated earnings data that were ill-equipped to

help identify bona fide EAP employees.

To address this problem, in the 2004 and 2019 rules the Department expressed its

commitment to regularly updating the salary levels.

13

In the 2016 rule, it included a regulatory

provision to automatically update the salary levels.

14

Based on its long experience with updating

the salary levels, the Department has determined that adopting a regulatory provision for

updating the salary levels to reflect current earnings data, with an exception for pausing future

updates under certain conditions, is the most viable and efficient way to ensure the EAP

exemption earnings thresholds keep pace with changes in employee pay and thus remain

effective in helping determine exemption status. This rule establishes a new updating

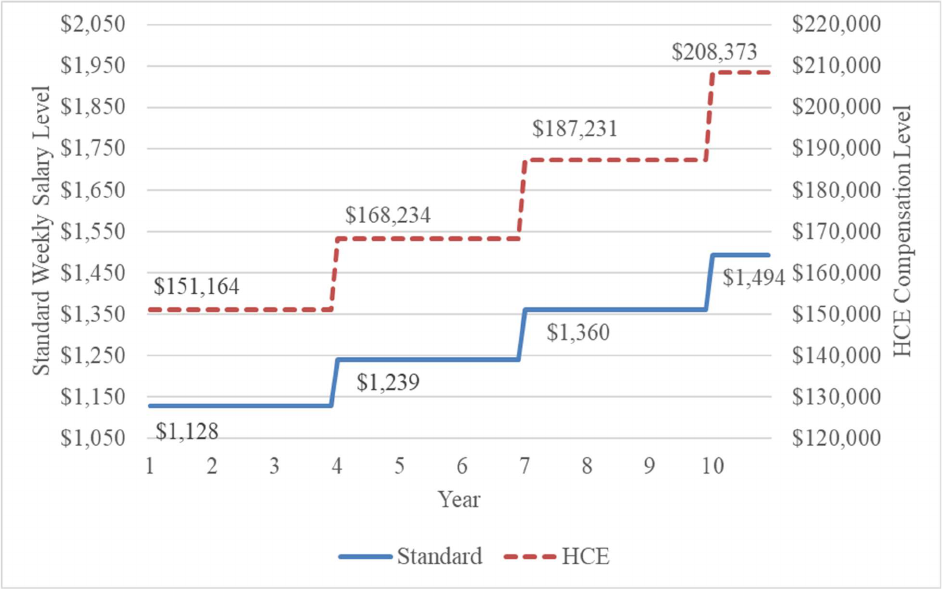

mechanism. The initial update to the standard salary level and the HCE total annual

compensation threshold will take place on July 1, 2024, and will use the methodologies in place

at that time (i.e., the 2019 rule methodologies), resulting in a $844 per week standard salary level

and a $132,964 HCE total annual compensation threshold. Future updates to the standard salary

level and HCE total annual compensation threshold with current earnings data will begin 3 years

after the date of the initial update (July 1, 2027), and every 3 years thereafter, using the

methodologies in place at the time of the updates. The Department anticipates that, by the time

12

84 FR 51250–51; 81 FR 32430; see also 69 FR 22164.

13

69 FR 22171; 84 FR 51251–52.

14

81 FR 32430.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

the first triennial update under the updating mechanism occurs, assuming the Department has not

engaged in further rulemaking, the new methodologies for the standard salary level and HCE

total annual compensation requirement established by this final rule will have become effective

and the triennial update will employ these new methodologies. The new updating mechanism

will allow for the timely, predictable, and efficient updating of the earnings thresholds.

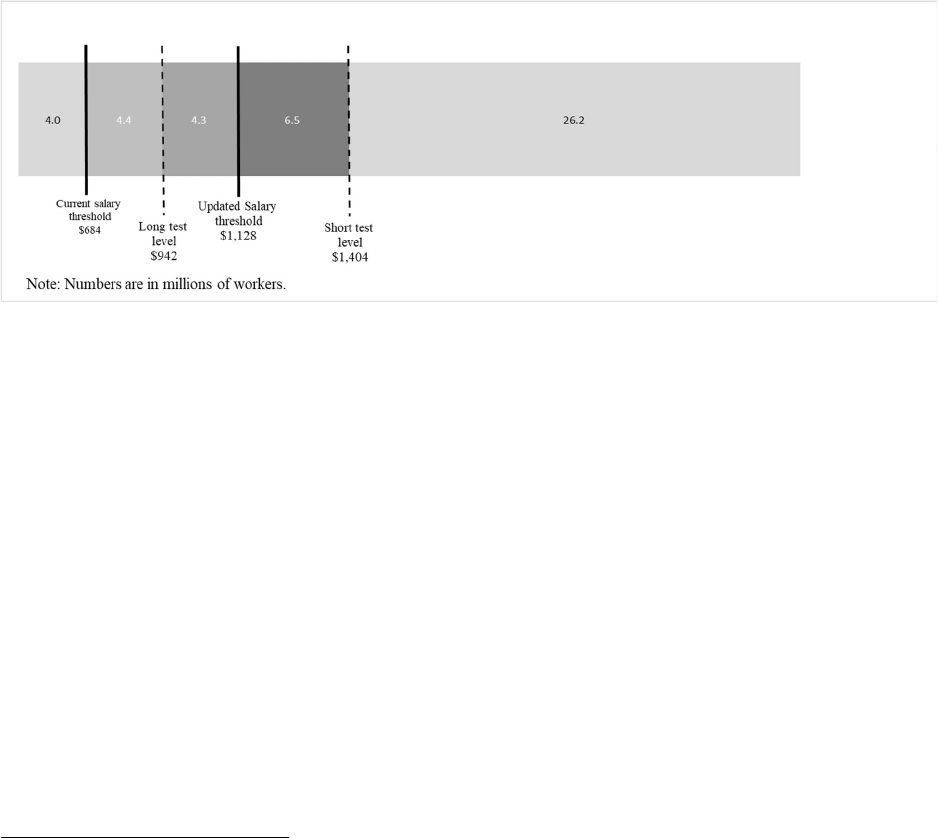

The Department estimates that in Year 1, approximately 1 million employees who earn at

least $684 per week but less than $844 per week will be impacted by the initial update applying

current wage data to the standard salary level methodology from the 2019 rule, and

approximately 3 million employees who earn at least $844 per week but less than the new

standard salary level of $1,128 per week will be impacted by the subsequent application of the

new standard salary level. See Table 25. As explained in section V.B.4.ii, for 1.8 million of the

affected employees (including the 1 million impacted by the initial update), this rule will restore

overtime protections that they would have been entitled to under every rule prior to the 2019

rule. The Department also estimates that 292,900 employees who are currently exempt under the

HCE test, but do not meet the standard test for exemption, will be affected by the proposed

increase in the HCE total annual compensation level. Absent an employer increasing these

employees’ pay to at or above the new HCE level, the exemption status of these employees will

turn on the standard duties test (which these employees do not meet) rather than the minimal

duties test that applies to employees earning at or above the HCE threshold. The economic

analysis quantifies the direct costs resulting from this rule: (1) regulatory familiarization costs;

(2) adjustment costs; and (3) managerial costs. The Department estimates that total annualized

direct employer costs over the first 10 years will be $803 million with a 7 percent discount rate.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

This rule will also give employees higher earnings in the form of transfers of income from

employers to employees. The Department estimates annualized transfers will be $1.5 billion,

with a 7 percent discount rate.

II. Background

A. The FLSA

The FLSA generally requires covered employers to pay employees at least the federal

minimum wage (currently $7.25 an hour) for all hours worked and overtime premium pay of at

least one and one-half times the employee’s regular rate of pay for all hours worked over 40 in a

workweek.

15

However, section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA, codified at 29 U.S.C. 213(a)(1), provides

an exemption from both minimum wage and overtime pay for “any employee employed in a

bona fide executive, administrative, or professional capacity . . . or in the capacity of [an] outside

salesman (as such terms are defined and delimited from time to time by regulations of the

Secretary [of Labor], subject to the provisions of [the Administrative Procedure Act] . . . ).” The

FLSA does not define the terms “executive,” “administrative,” “professional,” or “outside

salesman,” but rather directs the Secretary to define those terms through rulemaking. Pursuant to

Congress’s grant of rulemaking authority, since 1938 the Department has issued regulations at 29

CFR part 541 to define and delimit the scope of the section 13(a)(1) exemption.

16

Because

Congress explicitly gave the Secretary authority to define and delimit the specific terms of the

exemption, the regulations so issued have the binding effect of law.

17

15

See 29 U.S.C. 206(a), 207(a).

16

See Helix Energy Solutions Group, Inc. v. Hewitt, 143 S.Ct. 677, 682 (2023) (“Under [section

13(a)(1)], the Secretary sets out a standard for determining when an employee is a ‘bona fide

executive.’”).

17

See Batterton v. Francis, 432 U.S. 416, 425 n.9 (1977).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

The exemption for executive, administrative, or professional employees was included in

the original FLSA legislation passed in 1938.

18

It was modeled after similar provisions contained

in the earlier National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 and state law precedents.

19

As the

Department has explained in prior rules, the EAP exemption is premised on two policy

considerations. First, the type of work exempt employees perform is difficult to standardize to

any time frame and cannot be easily spread to other workers after 40 hours in a week, making

enforcement of the overtime provisions difficult and generally precluding the potential job

expansion intended by the FLSA’s time-and-a-half overtime premium.

20

Second, exempt

workers typically earn salaries well above the minimum wage and are presumed to enjoy other

privileges to compensate them for their long hours of work. These include, for example, above-

average fringe benefits and better opportunities for advancement, setting them apart from

nonexempt workers entitled to overtime pay.

21

Section 13(a)(1) exempts covered EAP employees from both the FLSA’s minimum wage

and overtime requirements. However, because of their long hours of work, its most significant

impact is its exemption of these employees from the Act’s overtime protections, as discussed in

section VII.C.4. An employer may employ such exempt employees for any number of hours in

the workweek without paying an overtime premium. Some state laws have stricter standards to

be exempt from state minimum wage and overtime protections than those which exist under

18

See Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938, Pub. L. 75-718, 13(a)(1), 52 Stat. 1060, 1067 (June 25,

1938).

19

See National Industrial Recovery Act, Pub. L. 73-67, ch. 90, title II, 206(2), 48 Stat 195, 204-5

(June 16, 1933).

20

See Report of the Minimum Wage Study Commission, Volume IV, pp. 236 and 240 (June

1981).

21

See id.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

federal law, such as higher salary levels or more stringent duties tests. The FLSA does not

preempt any such stricter state standards.

22

If a state establishes a higher standard than the

provisions of the FLSA, the higher standard applies in that state.

B. Regulatory History

The Department’s part 541 regulations have consistently looked to the duties performed

by the employee and the salary paid by the employer in determining whether an individual is

employed in a bona fide executive, administrative, or professional capacity. Since 1940, the

Department’s implementing regulations have generally required each of the following three

prongs to be satisfied for the exemption to apply: (1) the employee must be paid a predetermined

and fixed salary that is not subject to reduction because of variations in the quality or quantity of

work performed (the salary basis test); (2) the amount of salary paid must meet a minimum

specified amount (the salary level test); and (3) the employee’s job duties must primarily involve

executive, administrative, or professional duties as defined by the regulations (the duties test).

1. The Part 541 Regulations from 1938 to 2004

The Department’s part 541 regulations have always included earnings criteria. From the

first Part 541 regulations, there has been “wide agreement” that the amount paid to an employee

is “a valuable and easily applied index to the ‘bona fide’ character of the employment for which

[the] exemption is claimed[.]”

23

Because EAP employees “are denied the protection of the

[A]ct[,]” they are “assumed [to] enjoy compensatory privileges” which distinguish them from

22

See 29 U.S.C. 218(a).

23

“Executive, Administrative, Professional . . . Outside Salesman” Redefined, Wage and Hour

Division, U.S. Department of Labor, Report and Recommendations of the Presiding Officer

[Harold Stein] at Hearings Preliminary to Redefinition (Oct. 10, 1940) (Stein Report) at 19.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

nonexempt employees, including substantially higher pay.

24

Additionally, the Department has

long recognized that the salary level test is a useful criterion for helping identify bona fide EAP

employees and provides a practical guide for employers and employees, thus tending to reduce

litigation and ensure that nonexempt employees receive the overtime protection to which they

are entitled.

25

These benefits accrue to employees and employers alike, which is why, despite

disagreement over the appropriate magnitude of the part 541 earnings thresholds, an

“overwhelming majority” of stakeholders have supported the retention of such thresholds in prior

part 541 rulemakings.

26

The Department issued the first version of the part 541 regulations in October 1938.

27

The Department’s initial regulations included a $30 per week compensation requirement for

executive and administrative employees. It also included a duties test that prohibited employers

from claiming the EAP exemption for employees who performed “[a] substantial amount of

work of the same nature as that performed by nonexempt employees of the employer.”

28

The Department issued the first update to its part 541 regulations in October 1940,

29

following extensive public hearings.

30

Among other changes, the 1940 update newly applied the

24

Id.; see Report of the Minimum Wage Study Commission, Volume IV, p. 236 (“Higher base

pay, greater fringe benefits, improved promotion potential and greater job security have

traditionally been considered as normal compensatory benefits received by EAP employees,

which set them apart from non-EAP employees.”).

25

See 84 FR 51237; see also Report and Recommendations on Proposed Revisions of

Regulations, Part 541, by Harry Weiss, Presiding Officer, Wage and Hour and Public Contracts

Divisions, U.S. Department of Labor (June 30, 1949) (Weiss Report) at 8.

26

84 FR 51235; see also Stein Report at 5, 19; Weiss Report at 9.

27

3 FR 2518 (Oct. 20, 1938).

28

Id.

29

5 FR 4077 (Oct. 15, 1940).

30

See Stein Report.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

salary level requirement to professional employees; added the salary basis requirement to the

tests for executive, administrative, and professional employees; and introduced a 20 percent cap

on the amount of nonexempt work that executive and professional employees could perform

each workweek, replacing language which prohibited the performance of a “substantial amount”

of nonexempt work.

31

The Department conducted further hearings on the part 541 regulations in 1947

32

and

issued revised regulations in December 1949.

33

The 1949 rulemaking updated the salary levels

set in 1940 and introduced a second, less stringent duties test for higher paid executive,

administrative, and professional employees.

34

Thus, beginning in 1949, the part 541 regulations

contained two tests for the EAP exemption. These tests became known as the “long” test and the

“short” test. The long test paired a lower earnings threshold with a more rigorous duties test that

generally limited the performance of nonexempt work to no more than 20 percent of an

employee’s hours worked in a workweek. The short test paired a higher salary level and a less

rigorous duties test, with no specified limit on the performance of nonexempt work. From 1958

until 2004, the regulations in place generally set the long test salary level at a level designed to

exclude from exemption approximately the lowest-paid 10 percent of salaried white-collar

employees who performed EAP duties in lower-wage areas and industries and set the short test

salary level significantly higher.

35

The salary and duties components of each test complemented

31

5 FR 4077.

32

See Weiss Report.

33

See 14 FR 7705 (Dec. 24, 1949).

34

Id. at 7706.

35

See Report and Recommendations on Proposed Revision of Regulations, Part 541, Under the

Fair Labor Standards Act, by Harry S. Kantor, Assistant Administrator, Office of Regulations

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

each other, and the two tests worked in combination to determine whether an individual was

employed in a bona fide EAP capacity. Lower-paid employees who met the long test salary level

but did not meet the higher short test salary level were subject to the long duties test which

ensured that these employees were employed in an EAP capacity by limiting the amount of time

they could spend on nonexempt work. Employees who met the higher short test salary level were

considered to be more likely to meet the requirements of the long duties test and thus were

subject to a short-cut duties test for determining exemption status.

Additional changes to the regulations, including salary level updates, were made in

1954,

36

1958,

37

1961,

38

1963,

39

1967,

40

1970,

41

1973,

42

and 1975.

43

The Department revised the

part 541 regulations twice in 1992 but did not update the salary thresholds at that time.

44

None of

these updates changed the basic structure of the long and short tests.

The Department described the salary levels adopted in the 1975 rule as “interim rates,”

intended to “be in effect for an interim period pending the completion of a study [of worker

and Research, Wage and Hour and Public Contracts Divisions, U.S. Department of Labor (Mar.

3, 1958) (Kantor Report) at 6-7. Under the two-test system, the ratio of the short test salary level

to the long test salary levels ranged from approximately 130 percent to 180 percent. See 81 FR

32403.

36

19 FR 4405 (July 17, 1954).

37

23 FR 8962 (Nov. 18, 1958).

38

26 FR 8635 (Sept. 15, 1961).

39

28 FR 9505 (Aug. 30, 1963).

40

32 FR 7823 (May 30, 1967).

41

35 FR 883 (Jan. 22, 1970).

42

38 FR 11390 (May 7, 1973).

43

40 FR 7091 (Feb. 19, 1975).

44

The Department first created a limited exception from the salary basis test for public

employees. 57 FR 37677 (Aug. 19, 1992). The Department also implemented a 1990 law

requiring it to promulgate regulations permitting employees in certain computer-related

occupations to qualify as exempt under section 13(a)(1) of the FLSA. 57 FR 46744 (Oct. 9,

1992); see Pub. L. 101-583, sec. 2, 104 Stat. 2871 (Nov. 15, 1990).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

earnings] by the Bureau of Labor Statistics . . . in 1975.”

45

However, those salary levels

remained in effect until 2004. The utility of the salary levels in helping to define the EAP

exemption decreased as wages rose during this period. In 1991, the federal minimum wage rose

to $4.25 per hour,

46

which for a 40-hour workweek exceeded the lower long test salary level of

$155 per week for executive and administrative employees and equaled the long test salary level

of $170 per week for professional employees. In 1997, the federal minimum wage rose to $5.15

per hour,

47

which for a 40-hour workweek not only exceeded the long test salary levels, but also

was close to the higher short test salary level of $250 per week.

2. Part 541 Regulations from 2004 to 2019

The Department published a final rule in April 2004 (the 2004 rule)

48

that updated the

part 541 salary levels for the first time since 1975 and made several significant changes to the

regulations. Most significantly, the Department eliminated the separate long and short tests and

replaced them with a single standard test. The Department set the standard salary level at $455

per week, which was equivalent to the 20th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried

workers in the lowest-wage Census Region (the South) and in the retail industry nationally. The

Department paired the new standard salary level test with a new standard duties test for

executive, administrative, and professional employees, respectively, which was substantially

equivalent to the short duties test used in the two-test system.

49

45

40 FR 7091.

46

See Pub. L. 101-157, sec. 2, 103 Stat. 938 (Nov. 17, 1989).

47

See Pub. L. 104-188, sec. 2104(b), 110 Stat 1755 (Aug. 20, 1996).

48

69 FR 22122.

49

See id. at 22192–93 (acknowledging “de minimis differences in the standard duties tests

compared to the . . . short duties tests”).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

In the 2004 rule, the Department acknowledged that the switch to the single standard test

for exemption was a significant change in the regulatory structure,

50

and noted that the shift to

setting the salary level based on “the lowest 20 percent of salaried employees in the South, rather

than the lowest 10 percent” of EAP employees was made, in part, “because of the proposed

change from the ‘short’ and ‘long’ test structure[.]”

51

The Department asserted that elimination

of the long duties test was warranted because “the relatively small number of employees

currently earning from $155 to $250 per week, and thus tested for exemption under the ‘long’

duties test, will gain stronger protections under the increased minimum salary level which . . .

guarantees overtime protection for all employees earning less than $455 per week[.]”

52

The

Department acknowledged, however, that the new standard salary level was comparable to the

lower long test salary level used in the two-test system (i.e., if the Department’s long test salary

level methodology had been applied to contemporaneous data).

53

Thus, employees who would

have been subject to the long duties test with its limit on the amount of time spent on nonexempt

work if the two-test system had been updated were subject to the equivalent of the short duties

test under the new standard test. For example, under the 2004 rule’s standard test, an employee

50

See id. at 22126–28.

51

Id. at 22167.

52

Id. at 22126.

53

Id. at 22171. The Department last set the long and short test salary levels in 1975. Throughout

this preamble, when the Department refers to the relationship of salary levels set in this rule and

the 2004, 2016, and 2019 rules to equivalent long or short test salary levels, it is referring to

salary levels based on contemporaneous (at the relevant point in time) data that, in the case of the

long test salary level, would exclude the lowest-paid 10 percent of exempt EAP employees in

low-wage industries and areas and, in the case of the short test salary level, would be 149 percent

of a contemporaneous long test salary level. The short test salary ratio of 149 percent is the

simple average of the 15 historical ratios of the short test salary level to the long test salary level.

See 81 FR 32467 & n.149.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

who earned just over the rule’s standard salary threshold of $455 in weekly salary, and who met

the standard duties test, was exempt even if they would not have met the previous long duties test

because they spent more than 20 percent of their time performing nonexempt work. If the

Department had instead retained the two-test system and updated the long test salary level to

$455, that same employee would have been nonexempt because they would have been subject to

the long test’s more rigorous duties analysis due to their lower salary.

In the 2004 rule, the Department also created a new test for exemption for certain highly

compensated employees.

54

The HCE test paired a minimal duties requirement—customarily and

regularly performing at least one of the exempt duties or responsibilities of an EAP employee—

with a high total annual compensation requirement of $100,000, a threshold that exceeded the

annual earnings of approximately 93.7 percent of salaried workers nationwide.

55

The Department

also ended the use of special salary levels for Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands, as they

had become subject to the federal minimum wage since the Department last updated the part 541

salary levels in 1975, and set a special salary level only for American Samoa, which remained

not subject to the federal minimum wage.

56

The Department also expressed its intent “in the

future to update the salary levels on a more regular basis, as it did prior to 1975.”

57

In May 2016, the Department issued a final rule (the 2016 rule) that retained the single-

test system introduced in 2004 but increased the standard salary level and provided for regular

updating. Specifically, the 2016 rule (1) increased the standard salary level from the 2004 salary

54

69 FR 22172.

55

See id. at 22169 (Table 3).

56

Id. at 22172.

57

Id. at 22171.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

level of $455 to $913 per week, the 40th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried

workers in the lowest-wage Census Region (the South);

58

(2) increased the HCE test total annual

compensation amount from $100,000 to $134,004 per year;

59

(3) increased the special salary

level for EAP workers in American Samoa;

60

(4) allowed employers, for the first time, to credit

nondiscretionary bonuses, incentive payments, and commissions paid at least quarterly towards

up to 10 percent of the standard salary level;

61

and (5) added a mechanism to automatically

update the part 541 earnings thresholds every 3 years.

62

The Department did not change any of

the standard duties test criteria in the 2016 rule,

63

opting instead to adopt a standard salary level

set at the low end of the historical range of short test salary levels used in the pre-2004 two-test

system.

64

The 2016 rule was scheduled to take effect on December 1, 2016.

On November 22, 2016, the U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Texas issued

an order preliminarily enjoining the Department from implementing and enforcing the 2016

rule.

65

On August 31, 2017, the district court granted summary judgment to the plaintiff

challengers, holding that the 2016 rule’s salary level exceeded the Department’s authority and

invalidating the rule.

66

On October 30, 2017, the Department of Justice appealed to the U.S.

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, which subsequently granted the Department’s motion to

58

81 FR 32404–05.

59

Id. at 32428.

60

Id. at 32422.

61

See id. at 32425–26.

62

See id. at 32430.

63

Id. at 32444.

64

In the 2016 rule, the Department estimated the historical range of short test salary levels as

from $889 to $1,231 (based on contemporaneous earnings data). Id. at 32405.

65

See Nevada v. U.S. Department of Labor, 218 F. Supp. 3d 520 (E.D. Tex. 2016).

66

See Nevada, 275 F.Supp.3d 795.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

hold that appeal in abeyance while the Department undertook further rulemaking. Following an

NPRM published on March 22, 2019,

67

the Department published a final rule on September 27,

2019 (the 2019 rule),

68

which formally rescinded and replaced the 2016 rule.

The 2019 rule (1) raised the standard salary level from the 2004 salary level of $455 to

$684 per week, the equivalent of the 20th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried

workers in the lowest-wage Census Region (the South) and/or in the retail industry nationally;

(2) increased the HCE total annual compensation threshold from $100,000 to $107,432, the

equivalent of the 80th percentile of annual earnings of full-time salaried workers nationwide; (3)

allowed employers to credit nondiscretionary bonuses and incentive payments (including

commissions) paid at least annually to satisfy up to 10 percent of the standard salary level; and

(4) established special salary levels for all U.S. territories.

69

The 2019 rule did not make changes

to the standard duties test.

70

While using the same methodology used in the 2004 rule to set the

salary threshold, the Department did not assert that this methodology constituted the outer limit

for defining and delimiting the salary threshold. Rather, the Department reasoned the 2004

methodology was well-established, reasonable, would minimize uncertainty and potential legal

challenge, and would address the concerns of the district court that the 2016 rule over-

emphasized the salary level.

71

The Department acknowledged that the new standard salary level

67

See 84 FR 10900 (March 22, 2019).

68

See 84 FR 51230.

69

The Department established special salary levels of $455 per week for Puerto Rico, Guam, the

U.S. Virgin Islands, and the CNMI (effectively continuing the 2004 salary level); it also

maintained the 2004 rule’s $380 per week special salary level for employees in American

Samoa. Id. at 51246.

70

See id. at 51241–43.

71

See id. at 51242.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

was, unlike the salary level set in the 2004 rule, below the long test salary level used in the pre-

2004 two-test system.

72

As in its 2004 rule, the Department “reaffirm[ed] its intent to update the

standard salary level and HCE total annual compensation threshold more regularly in the future

using notice-and-comment rulemaking.”

73

The 2019 rule took effect on January 1, 2020.

74

C. Overview of Existing Regulatory Requirements

The part 541 regulations contain specific criteria that define each category of exemption

provided for in section 13(a)(1) for bona fide executive, administrative, professional, and outside

sales employees, as well as teachers and academic administrative personnel. The regulations also

define exempt computer employees under sections 13(a)(1) and 13(a)(17). The employer bears

the burden of establishing the applicability of any exemption.

75

Job titles and job descriptions do

not determine exemption status, nor does merely paying an employee a salary rather than an

hourly rate.

As previously indicated, to satisfy the EAP exemption, employees must meet certain tests

regarding their job duties

76

and generally must be paid on a salary basis at least the amount

72

Id. at 51244.

73

Id. at 51251.

74

A lawsuit challenging the 2019 rule was filed in August 2022. The district court upheld the

rule and an appeal of that decision was pending at the time the Department issued this final rule.

See Mayfield v. U.S. Department of Labor, 2023 WL 6168251 (W.D. Tex. Sept. 20, 2023),

appeal docketed, No. 23-50724 (5th Cir. Oct. 11, 2023).

75

See, e.g., Idaho Sheet Metal Works, 383 U.S. at 209; Walling, 330 U.S. at 547–48.

76

For a description of the duties that are required to be performed under the EAP exemption, see

§§ 541.100 (executive employees); 541.200 (administrative employees); 541.300, 541.303–.304

(teachers and professional employees); 541.400 (computer employees); 541.500 (outside sales

employees).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

specified in the regulations.

77

Some employees, such as doctors, lawyers, teachers, and outside

sales employees, are not subject to salary tests.

78

Others, such as academic administrative

personnel and computer employees, are subject to special, contingent earning thresholds.

79

The

standard salary level for the EAP exemption is currently $684 per week (equivalent to $35,568

per year), and the total annual compensation level for highly compensated employees under the

HCE test is currently $107,432.

80

A special salary level of $455 per week currently applies to

employees in Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S. Virgin Islands, and the CNMI;

81

a special salary level

of $380 per week applies to employees in American Samoa;

82

and employers can pay a special

weekly “base rate” of $1,043 per week to employees in the motion picture producing industry.

83

Nondiscretionary bonuses and incentive payments (including commissions) paid on an annual or

more frequent basis may be used to satisfy up to 10 percent of the standard or special salary

levels.

84

Under the HCE test, employees who currently receive at least $107,432 in total annual

compensation are exempt from the FLSA’s overtime requirements if they customarily and

regularly perform at least one of the exempt duties or responsibilities of an executive,

77

Alternatively, administrative and professional employees may be paid on a fee basis for a

single job regardless of the time required for its completion as long as the hourly rate for work

performed (i.e., the fee payment divided by the number of hours worked) would total at least the

weekly amount specified in the regulation if the employee worked 40 hours. See § 541.605.

78

See §§ 541.303(d); 541.304(d); 541.500(c); 541.600(e). Such employees are also not subject to

a fee basis test.

79

See § 541.600(c)–(d).

80

See §§ 541.600(a); 541.601(a)(1).

81

See §§ 541.100; 541.200; 541.300.

82

See §§ 541.100; 541.200; 541.300.

83

See § 541.709.

84

§ 541.602(a)(3).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

administrative, or professional employee identified in the standard tests for exemption.

85

The

HCE test applies only to employees whose primary duty includes performing office or non-

manual work.

86

Employees considered exempt under the HCE test must currently receive at least

the $684 per week standard salary portion of their pay on a salary or fee basis without regard to

the payment of nondiscretionary bonuses and incentive payments.

87

D. The Department’s Proposal

On September 8, 2023, consistent with its statutory authority to define and delimit the

EAP exemption, the Department published a Notice of Proposed Rulemaking (NPRM) to revise

the part 541 regulations.

88

The Department proposed to increase the standard salary level to the

35th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census

Region (currently the South), equivalent to $1,059 per week based on earnings data used in the

NPRM.

89

The Department also proposed to apply this updated standard salary level to the four

U.S. territories that are subject to the federal minimum wage—Puerto Rico, Guam, the U.S.

Virgin Islands, and the CNMI—and to update the special salary levels for American Samoa and

the motion picture industry in relation to the new standard salary level.

90

The Department

85

§ 541.601.

86

§ 541.601(d).

87

See § 541.601(b)(1); see also 84 FR 51249.

88

See 88 FR 62152.

89

The Department noted that the final rule would use the most recent earnings data available to

set the standard salary level, which would change the dollar amount of the resulting threshold.

See 88 FR 62152-53 n. 3.

90

In this final rule the Department is not finalizing its proposal in section IV.B.1 and B.2 of the

NPRM to apply the standard salary level to the U.S. territories subject to the federal minimum

wage and to update the special salary levels for American Samoa and the motion picture

industry. The Department will address these aspects of its proposal in a future final rule. While

the Department is not finalizing its proposal, it is making nonsubstantive changes in provisions

addressing the territories as a result of other changes in this final rule.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

additionally proposed raising the HCE test’s total annual compensation requirement to the annual

equivalent of the 85th percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried workers nationally,

equivalent to $143,988 per year based on earnings data used in the NPRM. Finally, the

Department proposed a new mechanism to update the standard salary level and the HCE total

annual compensation threshold every 3 years to ensure that they remain effective tests for

exemption.

The public comment period for the NPRM concluded on November 7, 2023. The

Department received approximately 33,300 comments in response to the NPRM during the 60-

day comment period.

91

Comments came from a diverse array of stakeholders, including

employees, employers, trade associations, small business owners, labor unions, advocacy groups,

nonprofit organizations, law firms, academics, educational organizations and representatives,

religious organizations, economists, members of Congress, state and local government officials,

tribal representatives, and other interested members of the public. All timely received comments

may be viewed on the https://www.regulations.gov website, docket ID WHD-2023-0001.

Commenter views on the merits of the NPRM varied widely. Some of the comments the

Department received were general statements of support or opposition, while many others

addressed the Department’s proposal in considerable detail. As with previous part 541

rulemakings, a majority of the total comments came from comment campaigns using similar or

identical template language. Such campaign comments expressed support or opposition to the

proposed salary level, and sometimes addressed other issues including applying the salary level

91

In regulations.gov, the number of comments received is listed as 33,310 and the number of

posted comments is 26,280. This difference is because one commenter, WorkMoney, attached

thousands of comments to their one submission.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

to teachers,

92

and concerns from nonprofit agencies. However, the Department also received

thousands of unique comments. Significant issues raised in the comments are discussed in this

final rule. Comments germane to the need for this rulemaking are discussed in section III,

comments about the NPRM’s proposals are discussed in section V, and comments about the

potential costs, benefits, and other impacts of this rulemaking are discussed in section VII. The

Department has carefully considered the timely submitted comments about the Department’s

proposal.

The Department received a number of comments on topics that are beyond the scope of

this rulemaking. A significant number of commenters (including a large comment campaign)

urged the Department to newly apply the part 541 salary criteria to teachers. The Department did

not solicit comment about the exemption criteria for teachers in the NPRM and, as many

commenters on this issue recognized, addressing this issue would require a separate rulemaking.

Other topics outside the scope of this rulemaking include, for example, a request that the

Department extend the right to overtime pay to medical residents, create exemptions from the

salary level test, allow employers to credit the value of board and lodging towards the salary

level, clarify issues related to the fluctuating workweek method of calculating overtime pay, or

create a “safe harbor” provision for restaurant franchisors. The Department is not addressing

these issues in its final rule.

Several stakeholders such as Catholic Charities USA and the National Council of

Nonprofits expressed concern about funding and reimbursement rates to meet potential new

92

As noted above, teachers are among the employees for whom there is no salary level

requirement under the part 541 regulations. See § 541.303(d).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

overtime expenses. The Department appreciates the concerns conveyed in these comments and

the challenges of adjusting public funding. As discussed in section V.B.4.iv, however, the

Department’s EAP regulations have never had special rules for nonprofit or charitable

organizations and employees of these organizations are subject to the EAP exemption if they

satisfy the same salary level, salary basis, and duties tests as other employees.

III. Need for Rulemaking

The goal of this rulemaking is to set effective earnings thresholds to help define and

delimit the FLSA’s EAP exemption. To achieve this goal, the Department is not only updating

the single standard salary level to account for earnings growth since the 2019 rule, but also to

build on the lessons learned in its most recent rulemakings to more effectively define and delimit

employees employed in a bona fide EAP capacity. To this end, the Department is finalizing its

proposed changes to the standard salary level and the HCE test’s total annual compensation

requirement methodologies. Additionally, to maintain the effectiveness of these tests, the

Department is finalizing an updating mechanism that will update these earnings thresholds to

reflect current wage data, initially on July 1, 2024 and every 3 years thereafter. The

Department’s response to commenter feedback on the specific proposals included in the NPRM

is provided in section V. This section explains the need for the Department to update the part 541

earnings thresholds and addresses commenter feedback on whether the earnings thresholds

established in the 2019 rule should be increased.

As the Department explained in the NPRM, there is a need for the Department to update

the salary level to fully restore the salary level’s screening function and to account for the shift to

a one-test system in the 2004 rule, which broadened the exemption by placing the entire burden

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

of this shift on employees who historically were entitled to the FLSA’s overtime protection

because they performed substantial amounts of nonexempt work and earned between the long

and short test salary levels, but became exempt because they passed the more lenient standard

duties test. Since switching from a two-test to a one-test system for defining and delimiting the

EAP exemption in 2004, the Department has followed different approaches to set the standard

salary level. In 2004, the Department used a methodology that produced a salary level amount

that was equivalent to the lower long test salary level under the two-test system.

93

This approach

continued to perform the historical screening function of the long salary test—providing

overtime protection to employees who earned less than the long test salary level. But it

broadened the exemption to include employees earning between the long and short test salary

levels who historically had not met the long duties test (and therefore were not considered bona

fide EAP employees) and now became exempt if they met the less rigorous standard duties test.

94

The Department followed this same methodology to set the standard salary level in 2019, but

applying the 2004 rule’s methodology to contemporaneous data in 2019 resulted in a salary level

that was lower than what would have been the equivalent of the long test salary level and thus

did not fulfill the historical screening function for low-paid employees.

95

This broadened the

EAP exemption even further by, for the first time, exempting a group of white-collar employees

earning below the equivalent of the long test salary level.

93

See 69 FR 22168–69.

94

Id. at 22214.

95

See 84 FR 51260 (Table 4) (showing that the salary level derived from the Department’s long

test methodology would have been $724 per week rather than the finalized $684 per week

amount).

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

To address the concern that the 2004 rule did not provide overtime compensation for

lower-salaried white-collar employees performing large amounts of nonexempt work, in 2016

the Department set the standard salary level using a methodology that produced a salary at the

low end of the historical range of short test salary levels.

96

This approach restored overtime

protection to lower-salaried white-collar employees who performed substantial amounts of

nonexempt work, but it also made nonexempt some employees paid below the new salary level

who performed only a limited amount of nonexempt work and would have been exempt under

the long duties test.

97

In the challenge to the 2016 rule, the district court expressed concern that

the 2016 rule conferred overtime eligibility based on salary level alone to a substantial number of

employees who would otherwise be exempt.

98

As explained in greater detail in section V.B, setting the standard salary level at the 35th

percentile of weekly earnings of full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage Census Region

($1,128 per week, $58,656 annually), which is below the midpoint between the long and short

tests, will work effectively with the standard duties test to better define and delimit the EAP

exemption, in part by more effectively accounting for the switch from a two-test to a one-test

system, and will reasonably distribute the impact of the shift by ensuring overtime protection for

some lower-salaried employees without excluding from exemption too many white-collar

employees solely based on their salary level.

99

The new standard salary level will also account

for earnings growth since the 2019 rule and fully restore the historical screening function of the

96

81 FR 32405.

97

See 84 FR 10908; 84 FR 51242.

98

See Nevada, 275 F.Supp.3d. at 806.

99

See section V.A.3.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

salary level test. At the same time, the duties test will continue to determine exemption status for

a large majority of all salaried white-collar employees subject to the part 541 regulations.

As the Department has explained,

100

earnings thresholds in the part 541 regulations

gradually lose their effectiveness as the salaries paid to nonexempt employees rise over time.

These impacts grow in the absence of increases to the salary threshold that keep pace with wage

growth. Moreover, the longer it takes for the Department to implement such increases, the larger

the increases must be to restore earning thresholds to maintain their effectiveness. More than 4

years have passed since the 2019 final rule established the current earnings thresholds. In the

intervening years, salaried workers in the U.S. economy have experienced a rapid growth in their

nominal wages, such that the current $684 per week salary level now corresponds to

approximately the 12th percentile of earnings of full-time salaried workers in the lowest-wage

Census Region and retail nationally. The longer the Department waits to update these earnings

thresholds, the less effective they become in helping define and delimit the EAP exemption. For

example, applying the 2019 standard salary level methodology to current earnings data will

result in a new threshold of $844 per week—a 23 percent ($160 per week) increase over the

current $684 salary level. Earnings for full-time wage and salary workers nationally have

increased even more rapidly, rising by 24 percent during this period.

101

The Department is also increasing the HCE total annual compensation threshold to the

annualized weekly earnings amount of the 85th percentile of full-time salaried workers

100

See, e.g., 84 FR 51250–51.

101

Estimate based on the change in median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and salary

workers from Q3 2019 to Q4 2023. BLS, Median usual weekly earnings of full-time wage and

salary workers by sex, quarterly averages, seasonally adjusted.

https://www.bls.gov/news.release/wkyeng.t01.htm.

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR

review process. Only the version published in the Federal Register is the official version.

nationally ($151,164). Similar to the standard salary level, nominal wage growth among higher-

wage workers has eroded the effectiveness of the HCE threshold; data shows that the $107,432

threshold now corresponds to the 70th percentile of annual earnings of full-time salaried workers

nationwide. Reapplying the 2019 methodology (annualized weekly earnings of the 80th

percentile of full-time salaried workers nationally) to current earnings data would result in a

threshold of $132,964 per year—a 24 percent increase over the current threshold of $107,432.

Increasing the HCE test’s total annual compensation threshold equivalent to the 85th percentile

of salaried worker earnings nationwide will result in an HCE threshold reserved for employees at

the top of today’s economic ladder and, unlike a lower threshold, not risk the unintended

exemption of large numbers of employees in high-wage regions.

Finally, the Department is adopting a mechanism to regularly update the thresholds for

earnings growth, which will ensure that the thresholds continue to work effectively to help

identify EAP employees. As noted above, the history of the part 541 regulations shows multiple,

significant gaps during which the salary levels were not updated and their effectiveness in

helping to define the EAP exemption decreased as wages increased. While the Department has

generally increased its part 541 earnings thresholds every 5 to 9 years in the 37 years between

1938 and 1975, more recent decades have included long periods without raising the salary level,

resulting in significant erosion of the real value of the threshold levels followed by unpredictable

increases. Routine updates of the earnings thresholds to reflect wage growth will bring certainty

and stability to employers and employees alike.

The Department received many comments addressing the adequacy of the current salary

and compensation thresholds set in the 2019 rule and the need for this rulemaking. Generally,

Disclaimer: This final rule has been approved by the Office of Management and Budget’s Office

of Information and Regulatory Affairs and has been submitted to the Office of the Federal

Register (OFR) for publication. It is currently pending placement on public inspection at the

OFR and publication in the Federal Register. This version of the final rule may vary slightly

from the published document if minor technical or formatting changes are made during the OFR