Arkansas Tech University Arkansas Tech University

Online Research Commons @ ATU Online Research Commons @ ATU

ATU Theses and Dissertations 2021 - Present Student Research and Publications

Winter 12-16-2023

The Relationship Between Student Engagement And ACT Aspire The Relationship Between Student Engagement And ACT Aspire

Reading Scores Among Ninth-Grade Students In One Northwest Reading Scores Among Ninth-Grade Students In One Northwest

Arkansas Junior High School Arkansas Junior High School

Dwight Vincent Jr.

Arkansas Tech University

Follow this and additional works at: https://orc.library.atu.edu/etds_2021

Part of the Educational Leadership Commons

Recommended Citation Recommended Citation

Vincent, Dwight Jr., "The Relationship Between Student Engagement And ACT Aspire Reading Scores

Among Ninth-Grade Students In One Northwest Arkansas Junior High School" (2023).

ATU Theses and

Dissertations 2021 - Present

. 53.

https://orc.library.atu.edu/etds_2021/53

This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Research and Publications at Online

Research Commons @ ATU. It has been accepted for inclusion in ATU Theses and Dissertations 2021 - Present by

an authorized administrator of Online Research Commons @ ATU. For more information, please contact

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENT ENGAGEMENT AND ACT ASPIRE

READING SCORES AMONG NINTH-GRADE STUDENTS IN ONE

NORTHWEST ARKANSAS JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL

By

DWIGHT VINCENT, JR.

Submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate College of

Arkansas Tech University

in partial fulfillment of the requirements

for the degree of

DOCTOR OF EDUCATION IN SCHOOL LEADERSHIP

December 2023

© 2023, Dwight Vincent, Jr.

ii

DEDICATION

I would like to thank my parents, Dwight and Melissia Vincent, and my sister

April Vincent, for always loving, encouraging, and supporting me. Also, I was blessed

with a second set of parents. I want to thank my Uncle Fred and Aunt Marilyn for the

impact that they have had on my life. I also want to thank Aunt B for being such a special

auntie. Lastly, I want to dedicate this dissertation, this doctoral degree, and my career to

my brother, Frank Watson. Frank passed away in November of 2022 while I was in this

program. I thought about quitting, but I knew Frank would want me to finish, so I

finished this program in honor of him. I have always been proud to be his little brother. I

know Frank is proud of me for finishing this program. I want to say thank you to Frank

for showing me, and everyone who knew him, how to live life.

iii

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I would like to thank God for bringing me to this place and this time in my life to

finish this dissertation and earn a terminal degree in education. I would like to thank Dr.

John Freeman for his patience, guidance, and for helping me get to the finish line. I

would also like to thank Dr. Steve Bounds for serving on my committee. I would like to

thank Rickey Hicks, who I met in 2014 while we were both coaching at Parkview.

Rickey Hicks has proven to be a true friend, and I am thankful for the impact he has had

on my personal and professional growth over the last nine years. I hope that one day, we

work in the same district together again in some capacity. I would like to thank my

childhood friends for their friendship and for our brotherhood. I would like to thank Dr.

Jeff Flanigan for pushing me to pursue a terminal degree in the first place. I met Dr. Jeff

Flanigan in the summer of 2013 when we were both coaching in the Blytheville School

District. In our very first conversation, he told me to “play chess, not checkers.” My first

chess move was that I listened to his advice, and I’ve been listening to his advice ever

since. Thank you for being a true friend and mentor to me as I navigate my career as an

educator. I would not have earned my last three degrees, including this doctoral degree, if

I had not met him. Now that I have earned this terminal degree, I can rightfully say,

“checkmate.”

iv

ABSTRACT

THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN STUDENT ENGAGEMENT AND ACT ASPIRE

READING SCORES AMONG NINTH-GRADE STUDENTS IN ONE

NORTHWEST ARKANSAS JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL

Dwight Vincent, Jr.

The purpose of this study was to examine the relationship between academic

achievement and attendance. Reading proficiency is foundational to overall academic

success. In this study, reading proficiency served as the operational definition for the

level of student academic success. Out-of-school suspension is a disciplinary

consequence as a result of student behavior and correlates to student attendance. This

quantitative, correlational study examined the relationship between student engagement,

as defined by student attendance and discipline, and reading proficiency, as measured by

the 2021-22 ACT Aspire Reading scores for ninth-grade students in one northwest

Arkansas junior high school.

Descriptive data analysis was conducted to show the demographic makeup of the

school and the frequencies and means of attendance and discipline data. Raw scores for

the ACT Aspire Reading Assessment were used as a measure of student academic

success. Using Spearman Rho and multiple linear regression analysis, the results of this

study revealed the effect of chronic absenteeism on the reading proficiency of these

ninth-grade students in one Northwest Arkansas junior high school. Three regression

models were formulated using student attendance, gender, and ethnicity as predictor

variables, with a combined 11.6% explanation for the variance in the reading scores.

While the analysis indicated that attendance, gender, and ethnicity predicted reading

scores, student discipline was removed from the regression analysis as a predictor

variable.

Conclusions from the research include that out-of-school suspensions have a

negative effect on reading proficiency due to their increasing student attendance.

Discipline alone did not appear to affect reading proficiency and academic achievement

significantly. The results support previous research in this field, indicating that students

with higher attendance tend to have better reading proficiency. This research suggests

that school leaders must provide alternatives to out-of-school suspensions and find

solutions to negative student behavior to increase instructional time. This research

contributes to the ongoing dialogue surrounding the negative academic impact of low

attendance, exacerbated by out-of-school suspensions and academic achievement.

Keywords: academic achievement, attendance, chronic absenteeism, ethnicity, gender,

lost instructional time, moderate absenteeism, out-of-school suspension, reading

proficiency, school discipline

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

DEDICATION……………………………………………………………………………. ii

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS……………………………………………………………….. iii

ABSTRACT……………………………………………………………………………... iv

LIST OF TABLES………………………………………………………………………... x

LIST OF FIGURES……………………………………………………………………… xi

I. INTRODUCTION……………………………………………………………………… 1

Background of the Problem………………………………………………………. 4

Statement of the Problem…………………………………………………………. 6

Purpose Statement………………………………………………………………… 6

Conceptual Framework…………………………………………………………… 7

Research Methods and Design Overview………………………………………… 7

Research Questions and Hypotheses……………………………………………... 8

Significance of the Study…………………………………………………………. 9

Delimitations…………………………………………………………………….. 10

Limitations………………………………………………………………………. 10

Definitions of Key Terms……………………………………………………... 10

Assumptions……………………………………………………………………... 14

Chapter Summary……………………………………………………………….. 14

Organization of the Study……………………………………………………….. 15

II. REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE…………………………………………………... 17

At-Risk Students and School Accountability…………………………………… 17

Affective, Cognitive, and Behavioral Student Engagement…………………….. 18

Accountability in Arkansas Schools…………………………………………….. 20

School Performance……………………………………………………... 20

School Quality and Student Success…………………………………….. 21

Student Engagement…………………………………………………….. 22

Reading at Grade Level…………………………………………………. 22

The American College Test……………………………………………... 23

The ACT Readiness Benchmark………………………………………… 24

The 2.8 GPA on a 4.0 Scale……………………………………………... 24

On-time Credits………………………………………………………….. 25

Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, or Concurrent Credit

Courses…………………………………………………………… 25

Student Attendance and Student Engagement…………………………………... 25

Student Discipline and Student Engagement……………………………………. 28

Attendance and Reading Scores………………………………………………….30

Effects of Lost Instructional Time on Reading Scores Due to Discipline………. 32

Chapter Summary……………………………………………………………….. 32

III. METHODOLOGY………………………………………………………………….. 34

Research Questions and Hypotheses……………………………………………. 35

Research Methodology………………………………………………………….. 36

Research Design………………………………………………………………….36

Population and Sample………………………………………………………….. 37

Setting…………………………………………………………………………… 38

Instrumentation………………………………………………………………….. 39

Data Sources…………………………………………………………………….. 40

Operational Definitions of Variables……………………………………………. 41

Data Collection………………………………………………………………….. 41

Data Analysis……………………………………………………………………. 42

Assumptions……………………………………………………………………... 44

Ethical Assurances………………………………………………………………. 45

Chapter Summary……………………………………………………………….. 45

IV. DATA ANALYSIS AND RESULTS……………………………………………... 46

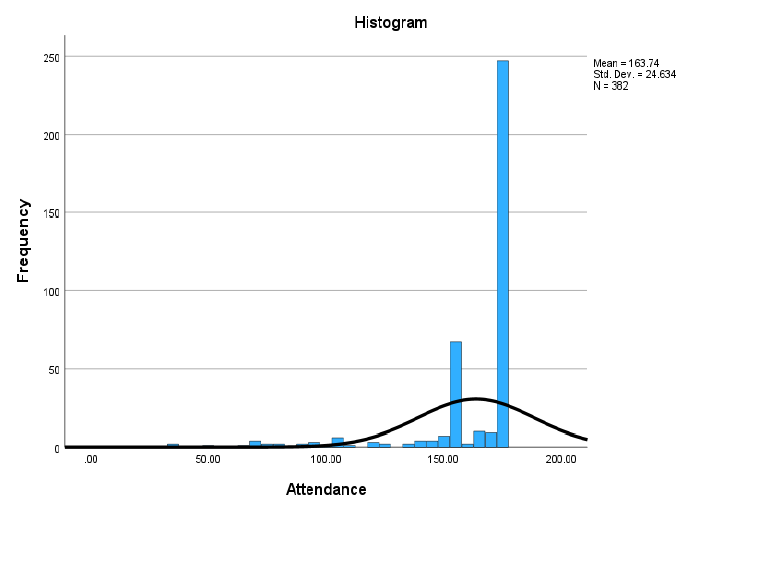

Descriptive Results……………………………………………………………… 47

Data Collection………………………………………………………………….. 50

Data Analysis……………………………………………………………………. 50

Results…………………………………………………………………………… 51

Research Question 1 (RQ1)....................................................................... 51

Research Question 2 (RQ2)....................................................................... 55

Research Question 3 (RQ3)....................................................................... 56

Chapter Summary……………………………………………………………….. 63

V. CONCLUSIONS, IMPLICATIONS, AND RECOMMENDATIONS……………. 65

Summary of Results……………………………………………………………... 65

Implications for Educational Practice…………………………………………… 68

Recommendations for Educational Practice…………………………………….. 69

Recommendations for Future Research…………………………………………. 71

Study Summary………………………………………………………………….. 72

REFERENCES………………………………………………………………………….. 74

APPENDICES…………………………………………………………………………... 82

Appendix A: ATU IRB Approval Letter……………………………………… 83

Appendix B: District Approval to Conduct Study………………………………. 84

x

LIST OF TABLES

Table Page

1: Sample Population by Ethnicity and Gender…………………………………………. 39

2: Variables Analyzed and Statistical Analysis Used for Each Research Question…….. 43

3: Number of Chronic Absentees by Ethnicity and Gender…………………………….. 48

4: Number of Suspensions by Ethnicity and Gender……………………………………. 49

5: Correlation Results for Attendance and ACT Aspire Reading Scores……………….. 55

6: Correlation Results for Suspensions and ACT Aspire Reading Scores………………. 57

7: Coefficients for Regression Models………………………………………………….. 60

8: ANOVA Results for Regression Models……………………………………………... 62

9: Model Summary……………………………………………………………………… 63

xi

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure Page

1: Histogram Showing the Distribution of Attendance Data……………………………. 52

2: Histogram Showing the Distribution of ACT Aspire Reading Scores……………….. 53

3: Scatterplot of Attendance and ACT Aspire Reading Scores…………………………. 54

4: Scatterplot of Suspensions and ACT Aspire Reading Scores…………………………55

5: Scatterplot of z Prediction and z Residual Scores for ACT Aspire Reading…………. 58

6: Histogram Showing the Distribution of Unstandardized Residuals for ACT Aspire

Reading Scores………………………………………………………………………...61

1

CHAPTER I

INTRODUCTION

U.S. public education faces many obstacles in preparing all students to succeed

academically. The recent COVID-19 epidemic exacerbated obstacles that were already

existent in the schools by forcing an ill-prepared transition to online instruction. As the

nation returns to some semblance of normalcy in the schools, it is predicted that the

effects of the pandemic on student academic performance may be felt for years to come.

The immediate effects can be seen in the 2022 National Assessment of Educational

Progress (NAEP) results, which show the most significant decrease in scores nationally

since the assessment began.

Contrary to post-COVID education concerns, U.S. public schools struggled before

the pandemic. A litany of obstacles can be cited for poor academic performance. The

pandemic made it even more challenging to deal with those obstacles. Poverty, low

attendance, and discipline problems were just a few of the obstacles already contributing

to low academic performance at all grade levels, nationally and in Arkansas.

Student engagement is one obstacle that profoundly impacts academic success

(Varjas et al., 2009). If a student is not present and engaged during the teaching/learning

process, it becomes impossible for that student to succeed. While the research literature

regarding student engagement is vast and includes many variables, this study sought to

view student engagement in its most elemental state: attendance and discipline.

Identifying student engagement as the number of days the student is present at

school, compounded by the number of discipline referrals, provides evidence of how

engaged the student is with the school and his/her teachers and is actively contributing to

2

their academic success. Attendance and discipline referrals often affect at-risk students to

a higher degree because those students are already facing other issues unrelated to the

school environment that act as obstacles to academic success (Vargas et al., 2009).

Many issues, such as illness or lack of parental supervision, impact student

attendance. In truth, many legitimate issues related to attendance are outside the school's

control. However, one issue that is within the school’s control and may affect attendance

is the school’s discipline policy. If suspension or expulsion is a part of the punitive results

of various violations of the school’s discipline policy, then the policy contributes to the

low attendance problem. In effect, disciplinary punishment such as out-of-school

suspension, expulsion, and in-school suspension acts as covariates to attendance.

Disciplinary policies are developed at the district and school levels to provide

rules for maintaining an orderly learning environment. Students and parents are provided

access to a student policy handbook by the school administrators outlining those rules

and the consequences or penalties for breaking those rules. In many cases, the

disciplinary policies do not solve the underlying causes of disruptive behavior that leads

to suspension or expulsion (Tyre et al., 2011).

The impact of suspension and expulsion on the student’s academic success is

most pronounced in lost instructional time. Since at-risk students are often more likely to

engage in conduct that violates school rules, they also lose the most instructional time.

For example, students struggling with tardiness and absenteeism are often given

consequences such as detention, in-school suspension, or out-of-school suspension.

Tardiness and absenteeism result in lost instructional time, and the consequences for

3

violating school rules compound the issue by adding to lost instructional time (Tyre et al.,

2011).

Poverty is another obstacle to student academic success, contributing to student

attendance issues (D’Agostino et al., 2018). A student who lives in a low-income

environment may have more stress outside of the classroom due to home and

neighborhood factors, including drug use, violence, abuse, secondhand smoke, neglect,

and low academic expectations. Low-income students often have fewer academic

resources at home, such as a safe and quiet place to study, reliable home internet, or food

insecurity (D’Agostino et al., 2018). These factors can contribute to a student’s

disengagement from the learning process while at school and lead to higher rates of

absenteeism and discipline referrals.

Additionally, because of food insecurity and the threat of homelessness, students

missing school to work is prevalent in high-poverty areas (D’Agostino et al., 2018). The

extra income a teenager can bring home reduces the financial stress on the household,

and this often takes precedence over attending school. This issue is compounded in the

case of the teen parent. Teen parents are most common among teenagers who come from

low-income families (Shane, 1991).

Students who are teen parents often settle for entry-level income that does not

require a high school diploma over staying in school to earn a diploma. Data shows that

teen parents are less likely to attend and graduate from a postsecondary institution

(Shane, 1991). These issues surrounding poverty put the student at risk for poor academic

performance, affecting the student’s attendance, discipline, and ability to succeed in

school.

4

Background of the Problem

An at-risk student is a student who has a predisposition for poor academic

performance based on any number of factors (Rieg, 2007). Some of these factors include

living in a single-parent home, being a minority, having limited English language

proficiency, receiving at least one academic intervention, frequent absenteeism, retention

in one or more grades, severe behavior problems, low academic performance, low

socioeconomic status, and drug and alcohol use (Rieg, 2007). Concerning attendance and

discipline, a student who has missed 10% or more of the school year falls under chronic

absenteeism (Learning, 2022). This includes excused absences, unexcused absences, and

absences due to suspension.

More than 20% of students in the U.S. are chronically absent, with 10% of

Arkansas students being identified as such (Learning, 2022). Northwest Arkansas's

diverse student population mirrors that statewide average of 10% chronic absenteeism.

Chronic absenteeism means lost instructional time, which, in turn, directly affects student

academic success (Roby, 2004).

The National Assessment of Educational Progress (NAEP), or The Nation’s

Report Card, is a standardized test given to fourth-, eighth-, and twelfth-graders to

measure their academic achievement in Reading, Math, and Science. The 2022 NAEP

results show that nationally, only 29% of eighth graders read proficiently on grade level,

while only 26% of Arkansas eighth graders were proficient in reading.

As a result of poor attendance and discipline, a student who does not read on

grade level usually struggles with content in every other subject area. If the student is not

reading on grade level, the student does not have the academic foundation to be

5

successful on grade level in any other subject. Mathematics primarily deals with

numbers, but students must be able to read at grade level to understand instructions for

mathematics assignments. Every other core subject is reading intensive, including

English Language Arts, Social Studies, and Science. Reading achievement strongly

correlates to overall academic success (Baysu et al., 2023).

The Arkansas Department of Education uses a formula that produces a school

letter grade to determine a school’s effectiveness (Learning, 2023). Formulating school

letter grades is an intricate process, with 17 modules contributing to a formula

determining a letter grade (Learning, 2023). The modules measure various aspects of the

school, including student attendance, teacher quality, student performance on

standardized tests, school safety, and student discipline, to name a few data sources

(Learning, 2023).

Of the 17 school report card modules, this research study included the three

indicators most closely related to student engagement. These three modules are School

Quality and Student Success, School Performance, and School Environment (Learning,

2023). These three modules relate to the research on student engagement and align with

the independent variables, attendance and discipline, and the dependent variable, ACT

Aspire reading test scores.

From an administrative standpoint, school leaders must understand that many of

our students need parental support and encouragement to perform well academically

(Allensworth & Evans, 2016). An administrator must have effective interventions to

improve student engagement for students who typically have disproportionately low

attendance and disproportionately high discipline referrals (Montero-Sieburth & Turcatti,

6

2022). With that, this research attempted to show the relationship and predictability of

attendance and discipline as a measure of student engagement in a Northwest Arkansas

junior high school on ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores.

Statement of the Problem

Student engagement reflects a student's passion or motivation to succeed

academically. It is reflected in the quality of a student’s relationship with family, school

staff, and peers (Li & Xue, 2023; Montero-Sieburth, 2022). It can also be reflected in the

student's effort to double-check school work after completion, seek tutoring, and extend

learning beyond the classroom (Shin & Bolkan, 2021). It reflects the student’s perception

of the relevance of the curriculum and school to the student’s life outside and after high

school (Rose & Bowen, 2021). If student engagement is low or non-existent, it can be

predicted that student academic success will suffer. Therefore, the problem addressed by

this study was to determine the relationship between student engagement and academic

success as measured by scores on the ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores for one

Northwest Arkansas junior high school.

For this study, student engagement was operationally defined by the level of

attendance and disciplinary referrals by ninth-grade students in the participating junior

high school and served as the independent variables. Academic success was measured by

ACT Aspire Reading Assessment scores that served as the dependent variable.

Purpose Statement

This study aimed to examine the relationship between student engagement, as

measured by the level of student attendance and disciplinary referrals, and the reading

scores for these participating ninth-grade junior high school students. Students in

7

Arkansas public schools are required to take a standardized test, the ACT Aspire, which

measures reading ability. Considering attendance data, discipline data, and ACT Aspire

reading scores, the study aimed to show the correlation between student engagement and

reading. Since reading comprehension indicates overall academic achievement (Beluce et

al., 2018), if reading scores are suffering, finding solutions to the causes of those low

scores is incumbent upon schools. Therefore, if high absenteeism and discipline referrals

are one of the causes of low reading scores, administrators can focus on solutions to

absenteeism and discipline issues.

Conceptual Framework

Student engagement is a construct that affects academic achievement (Williams et

al., 2023). Recent research characterizes student engagement as the relationships with

peers, sponsors, teachers, and athletic coaches (Williams et al., 2023). These relationships

make up the affective aspect of student engagement. Behavioral engagement comprises

aspects of student engagement such as attendance, behavior, and discipline. Lastly,

feelings of motivation and a sense of belonging constitute cognitive engagement.

Cognitive engagement is essential because a positive relationship exists between

student interest in the curriculum and engagement in learning activities associated with

that given curriculum (Williams et al., 2023). This is further relevant because students

can perform better with a curriculum they are not necessarily interested in if there is some

other aspect of school, namely extracurricular activities, holding the students’ interest.

Research Methods and Design Overview

This quantitative study obtained student engagement data from the 2021-22

academic year for ninth-grade students at one Northwest Arkansas junior high school in

8

the form of attendance and discipline data. The data were retrieved from the school’s

student information system (SIS). The collection of student attendance and discipline data

allowed the examination of the level of student engagement.

Academic achievement was measured by examining ACT Aspire reading scores

for all ninth-grade students at one Northwest Arkansas junior high school. ACT Aspire

Reading scores broken down by demographics allowed for further examination of

academic achievement by gender and ethnicity.

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between student

engagement as defined by the number of days of attendance and discipline referrals

during the 2021-22 school year for the ninth-grade students in one Northwest Arkansas

junior high school and student academic success as measured by raw scores on the ACT

Aspire Reading Assessment. The following research questions and hypotheses guided the

study:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant relationship between student attendance and ninth-

grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high

school?

H

0

1: There is no statistically significant relationship between student attendance and

ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior

high school.

RQ2: Is there a statistically significant relationship between student discipline and ninth-

grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high

school?

9

H

0

2: There is no statistically significant relationship between student discipline and

ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior

high school.

RQ3: Do attendance, discipline, gender, and ethnicity predict ninth-grade ACT Aspire

Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high school?

H

0

3: Attendance, discipline, gender, and ethnicity do not predict ninth-grade ACT Aspire

Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high school.

Significance of the Study

The significance of this study lies in the results that may contribute to the vast

literature relating to student engagement and its impact on student academic success. For

the school participating in this study, it reflected how those ninth-grade students are

performing academically and how their level of student engagement is impacting that

success or lack of success. The results may provide this school and other similar schools

with a better understanding of how these variables relate and provide an impetus for

administrators and teachers to develop ways to increase student engagement and improve

student academic success. In addition, by including gender and ethnicity in the analysis, it

provided information that may assist in personalizing support based on the individualized

needs of students through disaggregation of data.

Reading scores were used in this study to reflect overall student academic success

due to the importance that reading ability plays in overall learning (Bowers & Schwarz,

2018). Chronically absent students have experienced so much learning loss that grade-

level reading standards become more challenging to maintain, regardless of individual

subject area (Bowers & Schwarz, 2018). This study sought to determine how detrimental

10

chronic absenteeism is to academic achievement and the importance of students being

present in the classroom.

Finally, this study may contribute to existing knowledge by advising educators

and parents that students perform better if they have good attendance and discipline rates,

thereby leading these stakeholders to seek solutions to the problem of low attendance

rates and reducing the number of discipline referrals in the schools.

Delimitations

This study examined and collected data from one grade level of one junior high

school in one area of Arkansas. The study does not account for additional outside

influences that may impact the standardized testing data collected, such as socioeconomic

status and quality of home life. The scores that were used are from ninth grade only. The

demographics only include gender and ethnicity. The indicators only include attendance

and discipline.

Limitations

The scope of this study was narrow, and the results may not be generalizable to

other geographical locations with differing demographics. Therefore, the results may only

reflect the school that participated in the study. Although the results may partially align

with other geographical areas of Arkansas, the process and investigative direction are

transferable.

Definitions of Terms

● ACT Aspire: end-of-year online summative assessment for grades 3-10 in English,

Reading, Math, Science, and Writing (Learning Services, 2022).

11

● Affective engagement: the emotional value a student holds toward their education.

This can be affected by curriculum interest, safety, relationships with teachers and

peers, parent support, a sense of belonging, and the perception of school as

valuable (Fisher & Frey, 2021).

● American College Testing (ACT): A standardized college admissions test that

comprises four subject areas, including English, Math, Reading, and Science.

Scoring ranges from one to thirty-six.

● At-risk students: students who have specific demographic characteristics such as

living in a single-parent home, being a minority, having limited English language

proficiency, receiving at least one academic intervention, frequent absenteeism,

retention in one or more grades, severe behavior problems, low academic

performance, low socioeconomic status, and drug and alcohol use are indicators

of an at-risk student (Rieg, 2007).

● Behavioral engagement: the observable act of students involved in learning,

characterized by school attendance, class participation, and classroom behavior

(Fisher & Frey, 2021).

● Breadth of involvement: the number of extracurricular activities a student

participates in.

● Child nutrition: federally assisted meal program operating in public and nonprofit

private schools and residential child care institutions. It provides children

nutritionally balanced, low-cost, or free breakfast and lunch each school day.

12

● Co-curricular activity: a school-sponsored activity, program, or learning

experience that complements the school’s academic curriculum (Abro et al.,

2018).

● Cognitive engagement: the extent to which students are willing and able to take

on the learning task (Fisher & Frey, 2021). This can be demonstrated through

time investment in learning.

● Culturally responsive instruction: using students’ customs, characteristics,

experience, and perspectives to improve classroom instruction.

● Depth of involvement: the amount of time or intensity level a student dedicates to

an extracurricular activity

● Effective school: an effective school has received an A or B letter grade from the

Arkansas Department of Education

● Extracurricular activity: a school-sponsored activity that students are

productively involved with outside of the classroom, including academic (i.e.,

performing arts, student government, and yearbook) and nonacademic (i.e.,

sports, vocational clubs, service clubs, and hobby clubs) (Palmer et al., 2017).

● Literacy: the student’s ability to read and write, often identified by a standardized

assessment

● Local control: a school part of a school district that is governed by a locally

elected school board

● Low achieving: for this study, a low achieving school has received a D or an F

letter grade from the Arkansas Department of Education based on the seventeen

modules used to produce a letter grade (Learning Services, 2022)

13

● Poverty: poverty can be defined as follows: (a) based on the federal government’s

formula of the poverty line, (b) based on free and reduced lunch formulas that

vary from state to state, or (c) based on particular characteristics and situations

people find themselves in because of the amount of monetary and related material

capital they have or lack (Burney & Beilke, 2008).

● School safety: schools and school-related activities where students are safe from

violence, bullying, harassment, the sale or use of illegal substances on school

grounds, and other emergencies.

● School turnaround: “Turnaround” refers to quickly realizing academic

achievement in schools that have long been failing schools (Peck & Reitzug,

2014).

● Secondary schools: For this study, a secondary school is a school that serves

grades 9-12 (Danzig & Aljarrah, 1999).

● Social-emotional learning: a methodology that helps students better comprehend

their emotions and demonstrate empathy for others

● State control: a school part of a district identified as low achieving by the

Arkansas Department of Education (ADE) for three consecutive years. ADE has

dissolved the locally elected school board.

● Student engagement: the student’s degree of interest in their education,

identifiable by data indicators such as attendance, discipline, and academic

achievement (Dickinson et al., 2021) (Li et al., 2023).

14

Assumptions

Student attendance and student discipline make up student engagement. Student

achievement improves as student engagement improves. This is true regardless of the

ethnicity and gender of students. Reading proficiency is an indicator of overall academic

achievement. Even for math, students must understand the instructions to perform math

operations. All other core subjects are reading intensive, including English Language

Arts, Science, and Social Studies. For this reason, reading proficiency indicates overall

academic achievement, which is why ACT Aspire Reading scores were included in this

research. The data provided included all students' best efforts in taking the reading ACT

Aspire Assessments.

Chapter Summary

Student engagement reflects a student’s passion or interest level toward their

education (Li & Xue, 2023). Student engagement can be reflected in the quality of a

student’s relationship with family, school staff, and peers (Montero-Sieburth & Turcatti,

2022). In terms of school data, student engagement can be measured using attendance

data and discipline data. Discipline data are relevant to attendance data because

disciplinary consequences often include removing the student from the classroom

(Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016).

A suspension is an example of discipline data that includes removing the student

from the classroom (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016). This is significant because

students often receive different instruction quality while suspended, contributing to

learning loss. Learning loss occurs when the student does not receive learning

opportunities in the classroom (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016).

15

Student engagement was determined by student attendance and discipline referral

data. Students absent less than five percent of the school year were at a low risk of

chronic absenteeism. Students absent from 5% up to 10% of the school year were at

moderate risk of chronic absenteeism. Students who were absent 10% or more of the

school year were considered to be in the category of chronic absenteeism. As it related to

this study, student discipline was associated with absenteeism. The number of out-of-

school suspension days due to student discipline was a construct in this study.

Organization of the Study

This correlational, quantitative study disaggregated student engagement data for

ninth-grade students at a northwest Arkansas junior high school from the school’s student

information system (SIS). These data were from the 2021-2022 school year to identify

possible trends between attendance, discipline, and academic achievement. Academic

achievement was explicitly measured by examining ACT Aspire reading scores. The

collection of student attendance and discipline data from the school’s student information

system (SIS) allowed for the examination of the level of student engagement, while ACT

Aspire Reading scores broken down by demographics permitted the analysis of academic

achievement by gender and ethnicity.

In Chapter 2, the researcher reviewed relevant literature covering the following

topics: ACT Aspire, literacy, student engagement, student attendance, and student

discipline. The ACT Aspire is a summative assessment that tests students in

Mathematics, English Language Arts, Science, Reading, and Writing. As per this study,

literacy was the degree to which students tested in Reading.

16

In Chapter 3, the researcher describes the research design and methods used to

conduct the study. This quantitative study examined data from the school’s student

information system (SIS) and ACT Aspire testing portal. These databases provided

student demographic data, ethnicity, and gender without identifying individual students

by name. The data were collected from the most recent testing window during the 2021-

2022 school year to identify possible relationships between student attendance, student

discipline, and ACT Aspire reading scores by ethnicity and gender. The data collection

from the most recent school year's testing window allowed for the timeliest data available

about this school. The chapter also details the instrumentation, data analysis, and results

from the study.

In Chapter 4, the researcher presents the results from the statistical analysis and

how those results addressed the three guiding research questions. Chapter 5 presents the

conclusions and implications of those results and provides recommendations for practice

for school leaders and further study. Finally, the researcher provides an overall summary

and reflection on the study in that chapter.

17

CHAPTER II

REVIEW OF THE LITERATURE

The literature review was organized to reflect the relationship between student

engagement, reading proficiency, and overall academic achievement across subgroups.

EBSCOHost was used to locate peer-reviewed articles using search terms applicable to

the research. These terms included student engagement, attendance, absenteeism, chronic

absenteeism, at-risk, discipline, out-of-school suspension, reading comprehension,

reading proficiency, and lost instructional time. Research related to student engagement,

absenteeism, and chronic absenteeism were reviewed in relation to student attendance.

The terms at-risk, discipline, and out-of-school suspension also affect attendance through

consequences of student behavior. Absenteeism due to student behavior, in turn, affects

reading comprehension, reading proficiency, and overall academic achievement.

At-Risk Students and School Accountability

Much research has been conducted on at-risk students and school accountability.

An at-risk student has specific predispositions usually align with lower academic

achievement (Rury et al., 2022). These predispositions include coming from a single-

parent home, being a minority, having low socioeconomic status, being an English

language learner, having been previously retained, frequent absenteeism, severe behavior

problems, homelessness, and teen parenthood (Rury et al., 2022).

Along the same lines, a school with a high percentage of at-risk students will need

more intensive support to meet its at-risk students' needs. These supports include safety

and security at school, meal programs, academic intervention, social and emotional

instruction, and adequate housing (Hughes & Adera, 2006).

18

Concerning school accountability in Arkansas, the school environment, student

performance in response to academic intervention, and student performance in response

to social and emotional instruction are all school accountability measures (Lasater et al.,

2021). The performance of at-risk students has been studied, but this research focused on

how at-risk students affect school accountability from the lens of student engagement.

Affective, Cognitive, and Behavioral Student Engagement

Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement are types of student engagement

with distinct characteristics (Fisher & Frey, 2021). Research shows a strong correlation

between affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement and academic achievement.

Affective engagement concerns students' emotional value toward their education (Fisher

& Frey, 2021). This is not to be confused with social-emotional learning, which involves

teaching students’ general emotional maturity, not necessarily toward curriculum or

school (Neth et al., 2020).

One aspect of affective engagement is the student’s interest in the curriculum

(Fisher & Frey, 2021). Best practices call for teachers to use instructional strategies that

engage student interests regardless of ethnicity, gender, and other identifiers (Abacioglu

et al., 2020). This is culturally responsive teaching (Abacioglu et al., 2020). At the same

time, the curriculum is the curriculum, and students have a particular intrinsic motivation

to want to learn it. Intrinsic motivation can fluctuate and can be positively affected by a

healthy extracurricular activity experience (Daniels, 2017).

Safety is another facet of affective engagement (Fisher & Frey, 2021). Students

face many issues regarding school safety, including bullying, cyberbullying, and the

school's physical environment (Varjas et al., 2009). Students feel safe at school, which

19

has a physical component addressed by school staff and an emotional component built

through extracurricular activity participation (Varjas et al., 2009). One of the most

impactful aspects of affective engagement is the relationship-building students'

experience with staff and peers (Li et al., 2022). These relationships create a sense of

belonging, intrinsic motivation, and value in school because of the relationships created

there (Li et al., 2022).

Behavioral engagement is the observable act of students involved in learning.

Behavioral engagement is characterized by attendance and behavior (Fisher & Frey,

2021). Concerning extracurricular activities, there is usually an attendance requirement

and a behavior requirement to participate (Shaffer, 2019). Naturally, students

participating in extracurricular activities tend to have a higher attendance rate and a lower

rate of discipline infractions than students who do not participate in extracurricular

activities (Shaffer, 2019).

Cognitive engagement is the extent to which students are willing and able to take

on the learning task (Fisher & Frey, 2021). Extracurricular activities serve as a

motivational factor for some students in the sense that students understand they must put

forth effort in the classroom to be able to participate in extracurricular activities (Power et

al., 2009). Students may also find themselves in before-school, after-school, or weekend

tutoring to maintain eligibility for extracurricular activity participation (Power et al.,

2009). Either way, students participating in extracurricular activities display academic

behaviors consistent with a student who intends to stay in school, unlike academic

behaviors of students at risk of dropping out of school (Power et al., 2009).

20

This study investigated affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement and how

these three engagement types impact academic outcomes through the scope of

extracurricular activity participation. The study examined whether extracurricular

activities sharpen students' affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement outcomes.

Accountability in Arkansas Schools

School Performance

All Arkansas schools serving grades 3-10 must administer the ACT Aspire. This

summative assessment is given at the end of the school year in a specific testing window

that begins in April and ends in May. Students are tested in English, Reading, Math,

Science, and Writing. Schools should aim to test every student in their respective grade,

with a grace of 5%, meaning schools should test 95% of students in all five areas in every

grade that the school serves from grades 3-10. Schools have flexibility within a testing

window, and all five tests take approximately five hours to complete. Schools must also

offer accessibility features for all students.

This is usually not a problem as there are Arkansas state and federal requirements

for schools to offer these features to students any other day of the school year. Schools

must also provide accommodations for qualifying students. Like accessibility features,

schools already offer accommodations to qualifying students, so there will be no changes

concerning ACT Aspire testing. With any other school-wide function, the best practice in

the administration of the ACT Aspire is for the Special Education teachers and Special

Education director to be involved in the planning process (Essex, 1962).

Schools receive a predicted score for the ACT for students in grades 7-10 based

on the student’s performances on the five parts of the ACT Aspire. After receiving these

21

data, the best practice is for schools to provide ACT Prep interventions based on the

student’s needs in each subject area (Ray & Graham, 2021). There are a few ways that

high school students can receive ACT Prep intervention support. Virtual Arkansas offers

a course entitled ACT Prep Resources. This course includes diagnostics tests, drills,

videos, and content aligned to the reading, writing, math, science, and English portions of

the ACT. Many high schools offer summer ACT Prep courses.

Teachers provide intervention in reading, writing, math, science, and English so

that students have a deeper understanding of standards for these content areas. Many

colleges and universities also offer free ACT prep summer courses. This serves students

by putting them in a position to score better on the ACT and as a recruiting tool for these

postsecondary institutions. ACT offers learning tools and a practice test for students

interested in scoring higher on the ACT.

According to the modules, this applies to the college readiness module in keeping

with school improvement. Consequently, this is an example of modules being

interdependent upon one another and having an exponential effect on the overall school

letter grade. Lastly, schools must set their ACT Aspire testing schedule within the testing

window.

School Quality and Student Success

There are 11 indicators used to determine school quality and student success. The

indicators are on a point system. Higher school quality indicators receive more points,

while lower ones receive fewer. Schools receive a total score based on the points

accumulated by each student. Points are accumulated for each student for each indicator

22

to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value for overall school quality

and student success.

Student Engagement

Concerning the Arkansas Department of Education, student engagement is the

first indicator of school quality and student success. Student engagement measures

absenteeism. One point is assigned for each student absent less than 5% of the school

year. This student is considered low-risk. Half a point is given for each absent student,

anywhere from 5% to 10% of the school year. This student is considered a moderate risk.

Zero points are assigned for the absent student for over 10% of the school year. Points are

accumulated for each student for this indicator to produce a mean score, which is then

used to calculate a value for overall school quality and student success.

Concerning the operational definition of student engagement, attendance and

discipline are the two indicators of student engagement. Attendance refers to the presence

or absence of the student at school and in the classroom. Discipline data is relevant

because it often affects attendance. Discipline consequences that affect attendance

include detention, in-school suspension, out-of-school suspension, and expulsion.

Reading at Grade Level

Reading at grade level is another school quality and student success indicator.

Reading at grade level is measured in grades three through ten. Students are assigned one

point for scoring at ready or exceed and zero points for scoring at close or not ready.

Reading is one of the five ACT Aspire tested areas. Points are accumulated for each

student for this indicator to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value

for overall school quality and student success.

23

The American College Test

The American College Test, or ACT, indicates school quality and student success.

The ACT contains multiple-choice questions in English, Math, Reading, and Science.

The English portion of the ACT measures the student’s ability to make decisions to revise

and edit short texts and essays in different genres. Students have forty-five minutes to

answer seventy-five questions on the English portion of the ACT. The Math portion of

the ACT measures the student’s mathematical skills typically acquired in courses up to

the beginning of grade 12.

Students have 60 minutes to answer 60 questions on the Math portion of the ACT.

The Reading portion of the ACT measures the student’s ability to read closely, reason

logically about texts using evidence, and integrate information from multiple resources.

Students have 35 minutes to answer 40 questions on the Reading portion of the ACT. The

Science portion of the ACT measures the student’s interpretation, analysis, evaluation,

reasoning, and problem-solving skills required in Biology, Chemistry, Earth/Space

Sciences, and Physics. Students have 35 minutes to answer 40 questions on the Science

portion of the ACT. The Writing portion of the ACT is optional. The Writing portion of

the ACT measures the student’s writing skills taught in high school English classes and

entry-level college composition courses. Students have 40 minutes to respond to one

prompt.

Students can send their ACT scores directly to colleges and various scholarship

agencies. Students will receive a score between one and 36 on each test. These scores are

averaged to calculate one composite score. There is also a super score. There is no limit

to the number of times students can take the ACT. A super score is a composite score

24

calculated by taking the highest individual tested area of each ACT session the student

has ever earned. Some postsecondary institutions accept super scores for admission,

while others do not accept super scores for admission. Super scores are not considered in

determining the school letter grade. Points are accumulated for each student for this

indicator to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value for overall

school quality and student success.

The ACT Readiness Benchmark

The ACT Readiness Benchmark is another school quality and student success

indicator. This indicator follows the super score model, meaning individually tested areas

for all testing sessions from the previous three years are considered in calculating ACT

readiness. Students are assigned one-half of a point for ACT Reading scores of 22 or

higher. Students are assigned one-half of a point for ACT Math scores of 22 or higher.

Students are assigned one-half of a point for ACT Science scores of 23 or higher.

Students who have not scored the minimum score for each tested area receive zero points

toward the student’s total earned points. Points are accumulated for each student for this

indicator to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value for overall

school quality and student success.

The 2.8 GPA on a 4.0 scale

The 2.8 GPA on a 4.0 scale is another school quality and student success

indicator. The student’s final grade point average is pulled at the end of the student’s

senior year. Students with a grade point average equal to or greater than 2.8 receive one

point toward their total earned points. Students with a grade point average of less than 2.8

receive zero points toward their total earned points. Points are accumulated for each

25

student for this indicator to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value

for overall school quality and student success.

On-time Credits

On-time credits are another school quality and student success indicator. A

student receives one point if he earns 5.5 or more credits in the first year of high school,

11 credits by the end of the second year, and 16.5 credits by the third year. Students who

have recovered credits after the fact do not receive a point for on-time credits. Points are

accumulated for each student for this indicator to produce a mean score, which is then

used to calculate a value for overall school quality and student success.

Advanced Placement, International Baccalaureate, or Concurrent Credit Courses

A student receives one point if the student has earned at least one advanced

placement, international baccalaureate, concurrent credit, or ACE course in grades 9-12.

Students who have not yet earned this credit as ninth through eleventh graders are not

missing this point because this indicator is only exercised during what should be the

student’s last semester of high school. Points are accumulated for each student for this

indicator to produce a mean score, which is then used to calculate a value for overall

school quality and student success.

Student Attendance and Student Engagement

Student attendance is a critical factor in student engagement. Student attendance

is the presence of the student at school and in the correct classroom at the appropriate

time (Fallis & Opotow, 2003). It is important to note that student attendance refers to the

student being in the correct classroom at the appropriate time because the student can be

at the school campus but not in the classroom (Fallis & Opotow, 2003). A student can

26

intentionally skip a class by hiding on campus outside, in a class not assigned to the

student at the time, in or around an athletic facility on campus, in the media center,

roaming the halls, or several other places (Fallis & Opotow, 2003).

This action is commonly known as skipping and is not consistent with positive

attendance action (Fallis & Opotow, 2003). Skipping class is described in one study as

“the slow-motion process of dropping out made class-by-class and day-by-day in

students’ daily lives (Fallis & Opotow, 2003).” A student’s grades, on-time credits, and

the likelihood of graduation are significantly impacted by moderate absenteeism

(Allensworth & Evans, 2016). The construct of on-time credits concerns the pace at

which students earn credits. The Arkansas Department of Education’s effectiveness

system accounts for every student and awards the school full credit for the student who

has earned five and a half credits per school year. That is the minimum expectation, but

students can earn more credits per school year. However, earning five and a half credits

per school year is unlikely if the student falls into the chronic absenteeism category,

meaning the student misses ten percent or more of the school year.

Absenteeism is a more predictive graduation factor than race, gender, or poverty

(Allensworth & Evans, 2016). In one study, course attendance is eight times more

predictive of course failure in the freshman year than 8th-grade test scores (Allensworth

& Evans, 2016). This means that the data shows a student has a better chance to be

successful statistically speaking if the student is present, even more so than eighth-grade

test scores indicating the student is academically ready for the next grade level. The same

study shows that one week’s worth of absences per semester is associated with a 20%

decline in the probability of graduating from high school (Allensworth & Evans, 2016).

27

Middle school students who are chronically absent have a 50% chance of veering off

track in high school. These students have little chance of graduating without dramatically

changing their educational experience (Allensworth & Evans, 2016). Tardiness is also a

part of attendance. A tardy student has suffered learning loss by missing instruction

during tardiness, and chronic tardiness means more substantial learning loss (Tyre et al.,

2011). Therefore, tardiness is a part of student attendance.

There is existing research on the relationship between attendance and student

engagement. Higher attendance usually means a higher level of student engagement

(Herman, 2012). The problem with tardiness and excessive absenteeism is that they

produce learning loss. One way that significant learning loss occurs is when a student is

absent during instruction (Roby, 2004). Tier 1 instruction is the initial instruction given to

students by the teacher. There are intervention and remediation, which are small group or

individual follow-up instructional sessions, but the initial instruction is what students

miss when they are tardy or absent. This can be in the form of tardiness or being absent

altogether.

There is also existing research on the relationship between discipline and

extracurricular activity participation on student engagement. Discipline infractions may

result in removal from the classroom through suspension or expulsion, where Tier 1

instruction is initially provided (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016). The problem with

excessive discipline infractions is the consequences that come with them, sometimes

removal from the classroom, thereby causing learning loss (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy,

2016). Fewer discipline infractions usually mean a higher level of student engagement,

28

while extracurricular activity participation usually means more student engagement

(Dickinson et al., 2021).

Student Discipline and Student Engagement

Student discipline is a critical factor in student engagement. The prevalence of

learning loss when consequences are issued to maintain discipline in the school is an

issue with student engagement (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016). Many forms of school

discipline result in learning loss by removing the student from the classroom, causing the

student to miss Tier 1 instruction. Ironically, a student may receive a consequence of an

out-of-school suspension for skipping class. School discipline should act to remedy the

behavior, but out-of-school suspensions add to learning loss. Many education experts

argue against out-of-school suspensions altogether (Kennedy-Lewis & Murphy, 2016).

Detentions, in-school suspensions, out-of-school suspensions, and expulsions are

potential consequences for tardiness and chronic absenteeism. Detentions are usually

served before, during, or after school. If the detention is to be served during school, it

should be during the student’s time that does not require them to miss instruction (Welsh,

2022). For example, recess and lunch are times when students can serve detention

without missing instruction. The detention is meant to serve as an inconvenience to the

student, which is intended to motivate the student to avoid the inconvenience of detention

in the future by not being tardy anymore (Welsh, 2022). The opposite is true for in-school

suspensions and out-of-school suspensions in many cases. In-school suspensions can be

more effective than out-of-school suspensions for students who enjoy the social aspects

of being at school (Welsh, 2022). In-school suspension is inconvenient because students

are isolated from the rest of the student body and school activities (Welsh, 2022). This is

29

meant to motivate the student to avoid the inconvenience of in-school suspension by

correcting the behavior that landed the student in in-school suspension, which in this case

is tardiness.

This may only work for some students (Welsh, 2022). Another issue with in-

school suspension is the quality of instruction students receive while serving time in in-

school suspension (Welsh, 2022). Students are usually given review work, which

prevents new learning (Welsh, 2022). Even if the student is given classwork current to

the regular class setting, the student misses the Tier 1 instruction given in the classroom,

including all of the learning activities and supplemental resources that are a part of the

Tier 1 instruction (Welsh, 2022).

In-school suspension is essentially a learning loss (Welsh, 2022). Out-of-school

suspension is also a learning loss, but not as complex. Many students view out-of-school

suspension as a vacation day, especially students who do not have parental support at

home (Welsh, 2022). It is not viewed as a punishment at all. Students receive no

instruction during out-of-school suspension and will have missed a significant amount of

the curriculum upon return (Welsh, 2022). For these reasons, schools should work to

minimize or eliminate both in-school and out-of-school suspensions by addressing the

reasons behind the actions that cause students to be assigned these consequences (Maag

& Katsiyannis, 2010).

Wraparound services are a construct that can be used to remedy many underlying

issues causing tardiness and chronic absenteeism. The concept of a school providing

wraparound services is the idea of the school providing resources to the students outside

of instruction (Maag & Katsiyannis, 2010). These resources can include mental,

30

emotional, and social health support (Maag & Katsiyannis, 2010). Wraparound services

include physical support for homeless students and students from low-income families

regarding food, clothing, academic supplies, job placement, and housing (Basford et al.,

2021). Students needing wraparound services do not meet their most basic needs outside

of what the school can offer, which is the foundation of Maslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

(Basford et al., 2021).

A school providing wraparound services can fill a student's void and minimize or

eliminate discipline issues for that student (Basford et al., 2021). For example, a student

may skip a class to avoid bullying for wearing a dirty school uniform. The student may

not have a working washer and dryer at home. Wraparound services include giving the

student a clean set of school uniform clothes for the week, washing the dirty set, and then

returning this set to the student clean for the next week. For this student, a need has been

met, a discipline issue has been resolved, and learning loss has been eliminated by

providing wraparound services.

Attendance and Reading Scores

Reading scores are indicative of attendance (Gottfried, 2019). Chronic

absenteeism is a category of absenteeism achieved when a student has missed 10% or

more of the school year. Chronically absent students usually have lower reading scores

(Gottfried, 2019). Reading scores are affected by chronic absenteeism because students

miss grade-level vocabulary when grade-level standards are taught during Tier 1

instruction, which is simply the initial instruction provided to the class as a whole

(Grasley-Boy et al., 2022). During Tier 1 instruction, the teacher introduces new

vocabulary during the lesson). While students in the classroom are learning new

31

vocabulary presented in the lesson, the suspended student is missing the lesson, thereby

missing the growth in reading comprehension skills. The students in the classroom

continue to grow with each engaging lesson, while the suspended student continues to get

further behind with each missed day of instruction (Grasley-Boy et al., 2022).

Students who are not chronically absent usually have higher reading scores

(Gottfried, 2019). Students who are not chronically absent are present in the classroom

when the teacher introduces new grade-level vocabulary in the lesson. There is a greater

likelihood that the present student will grasp the new vocabulary than the likelihood of

the absent student learning the new vocabulary (Grasley-Boy et al., 2022). Concerning

academic achievement, the present student performs much better than the chronically

absent student (Grasley-Boy et al., 2022).

Reading scores indicate overall academic success (Lapasau et al., 2022). A

student reading on grade level usually achieves higher in all other subject areas than those

not reading on grade level. English Language Arts, Social Studies, and Science are all

reading-intensive subject areas, which is why the student’s ability to read on grade level

impacts overall academic achievement. However, reading on grade level also correlates

with higher math scores (Lapasau et al., 2022). A student must understand what a math

question or word problem asks them to do, how to manipulate the numbers, or what

operation to perform to succeed in math. In this way, reading comprehension or the

ability to read on grade level is a foundational tool for students to have overall higher

academic achievement versus not reading on grade level (Lapasau et al., 2022).

32

Effects of Lost Instructional Time on Reading Scores Due to Discipline

Discipline data indicates reading scores due to the learning loss that occurs from

disciplinary consequences (Arcia, 2006). Suspensions require students to be removed

from the classroom. This results in learning loss because the student is absent during

instructional time (Arcia, 2006). As a part of learning loss, students miss out on the grade

level standards being taught as a part of the curriculum presented to students during

instruction. A student who misses the introduction of new, grade-level, content-specific

vocabulary will only fall behind if the student receives the same quality of instruction

missed during the suspension, which is unlikely. For this reason, as disciplinary

infractions increase, reading scores decrease (Arcia, 2006).

Chapter Summary

The literature review details student engagement. Student engagement consists of

student attendance and student discipline. The results of student discipline often impact

student attendance, compounding the issue of a lack of student learning outcomes.

Affective, behavioral, and cognitive engagement are student actions and feelings toward

school. Extracurricular activities are tools schools can use to improve student

engagement. With high student engagement comes high student achievement. An

indicator of student achievement is reading comprehension. The ACT Aspire test

measures reading comprehension. All of these constructs come together to produce a

school’s overall effectiveness.

The following chapters will entail all of the data and the data’s implications of the

constructs above. The data will include student attendance, discipline, and ACT Aspire

33

reading scores, all broken down by ethnicity and gender. This data will show the

relationship between these constructs.

34

CHAPTER III

METHODOLOGY

This quantitative study sought to determine the relationship between student

engagement and academic achievement at an urban junior high school in Northwest

Arkansas. Student engagement was measured by the level of attendance and the number

of discipline referrals for students in this school. The purpose of this study was to identify

whether there is a relationship between student engagement and academic achievement as

identified by the individual student scores on the ACT Aspire Reading assessment. In

addition, the study sought to determine if there is an effect of gender and ethnicity upon

any relationship between student engagement and academic performance on the ACT

Aspire Reading assessment.

Student engagement is students' passion or interest level toward their education

(Li et al., 2023). Student engagement can be reflected in the quality of a student’s

relationship with family, school staff, and peers (Montero-Sieburth & Turcatti, 2022).

Student engagement can be reflected in the student's effort, such as double-checking

school work after completion, seeking tutoring, and extending learning beyond the

classroom (Shin & Bolkan, 2021). Student engagement is the student’s mentality

concerning the relevance of the curriculum and school to the student’s life outside and

after high school (Rose & Bowen, 2021). Concerning data, student engagement is

reflected in several ways, including attendance and discipline data. For this study, student

engagement will serve as the dependent variable. Attendance and discipline data will

serve as independent variables. The research will investigate the problem of student

underperformance as it relates to student engagement.

35

Research Questions and Hypotheses

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between student

engagement as defined by the number of days of attendance and discipline referrals

during the 2021-22 school year for the ninth-grade students in one Northwest Arkansas

junior high school and student academic success as measured by raw scores on the ACT

Aspire Reading Assessment. The following research questions and hypotheses guided the

study:

RQ1: Is there a statistically significant relationship between student attendance and ninth-

grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high

school?

H

0

1: There is no statistically significant relationship between student attendance and

ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior

high school.

RQ2: Is there a statistically significant relationship between student discipline and ninth-

grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high

school?

H

0

2: There is no statistically significant relationship between student discipline and

ninth-grade ACT Aspire Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior

high school.

RQ3: Do attendance, discipline, gender, and ethnicity predict ninth-grade ACT Aspire

Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high school?

H

0

3: Attendance, discipline, gender, and ethnicity do not predict ninth-grade ACT Aspire

Reading scores in the participating Northwest Arkansas junior high school.

36

Research Methodology

This quantitative study examined data from the school’s student information

system (SIS) and ACT Aspire testing portal. These databases will provide student

demographic data, namely ethnicity and gender, without identifying individual students

by name. The data were collected from the most recent testing window during the 2021-

2022 school year to identify possible relationships between student attendance, student

discipline, and ACT Aspire reading scores by ethnicity and gender. The data collection

from the most recent school year's most recent testing window allowed for the timeliest

data available about this school.

Research Design

The purpose of this study was to determine if there is a relationship between

student engagement and academic performance in reading among ninth-grade students at

one Northwest Arkansas junior high school. The variables examined include student

attendance, discipline, gender, and ethnicity as predictor variables, and raw scores on the

2021-22 ACT Aspire Reading Assessment for the ninth-graders in the participating

middle school were used as the outcome variable.

After receiving approval from the Arkansas Tech University Institutional Review

Board (IRB) (See Appendix A) and permission from the school district to retrieve the

required data (See Appendix B), the researcher proceeded to collect data for the study.

The data were collected directly from the school databases by school administrators, and

an Excel file containing the data was provided to the researcher.

Since the data were not randomly sampled and the selection of the participating

middle school was made through convenience sampling, the purpose of the study was not

37

to determine a cause and effect between the variables but to investigate the relationships

between the variables, to understand the effect of the selected predictor variables on the

outcome variable, reading scores.

Correlation and regression were selected as the research methods for this

quantitative design. The 2021-2022 school year data was used to identify possible

relationships between attendance, discipline, and academic achievement. ACT Aspire

Reading scores measured academic achievement. The collection of student attendance

and discipline data from the school’s student information system (SIS) allowed for the

examination of the level of student engagement, while ACT Aspire Reading scores

broken down by demographics allowed for the analysis of academic achievement by

gender and ethnicity.

After determining whether or not there was a statistically significant correlation

between student attendance, student discipline, and ACT Aspire Reading scores, multiple

regression analysis was used to assess the predictability of the outcome variable based on

the effect size of the predictor variables. Through this statistical method, the researcher

determined how much each predictor variable explains the variance in the outcome

variable, reading scores.

The researcher determined that the selected research methods and design provided

the best procedure for analyzing the collected data and answering the research questions

developed for this study.

Population and Sample

The population for this research study included all public Arkansas ninth-grade

students. The target population for this research study included one grade level of the

38

participating Arkansas junior high school. The convenience sample for this study

consisted of all ninth-grade students in this participating junior high school who received

a score on the ACT Aspire reading assessment during the 2021-22 school year.

Setting

The data were collected from the 2021-2022 ninth-grade class in the selected

Northwest Arkansas junior high school. The participating school houses two grade levels

with an enrollment of 720. The school's demographic makeup is 65% Hispanic, 18.6%

Pacific Islander, 10% White, 2.6% African American, 1.8% Asian, and 1.9% Other. The

student population of this school does not reflect the overall demographics of public