Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System

For use at 11:00 a.m., EDT

July 13, 2018

Monetary Policy rePort

July 13, 2018

Letter of transmittaL

B G

F R S

Washington, D.C., July 13, 2018

T P S

T S H R

The Board of Governors is pleased to submit its Monetary Policy Report pursuant to

section 2B of the Federal Reserve Act.

Sincerely,

Jerome H. Powell, Chairman

Adopted effective January24, 2012; as amended effective January30, 2018

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) is rmly committed to fullling its statutory

mandate from the Congress of promoting maximum employment, stable prices, and moderate

long-term interest rates. The Committee seeks to explain its monetary policy decisions to the public

as clearly as possible. Such clarity facilitates well-informed decisionmaking by households and

businesses, reduces economic and nancial uncertainty, increases the eectiveness of monetary

policy, and enhances transparency and accountability, which are essential in a democratic society.

Ination, employment, and long-term interest rates uctuate over time in response to economic and

nancial disturbances. Moreover, monetary policy actions tend to inuence economic activity and

prices with a lag. Therefore, the Committee’s policy decisions reect its longer-run goals, its medium-

term outlook, and its assessments of the balance of risks, including risks to the nancial system that

could impede the attainment of the Committee’s goals.

The ination rate over the longer run is primarily determined by monetary policy, and hence the

Committee has the ability to specify a longer-run goal for ination. The Committee rearms its

judgment that ination at the rate of 2percent, as measured by the annual change in the price

index for personal consumption expenditures, is most consistent over the longer run with the

Federal Reserve’s statutory mandate. The Committee would be concerned if ination were running

persistently above or below this objective. Communicating this symmetric ination goal clearly to the

public helps keep longer-term ination expectations rmly anchored, thereby fostering price stability

and moderate long-term interest rates and enhancing the Committee’s ability to promote maximum

employment in the face of signicant economic disturbances. The maximum level of employment

is largely determined by nonmonetary factors that aect the structure and dynamics of the labor

market. These factors may change over time and may not be directly measurable. Consequently,

it would not be appropriate to specify a xed goal for employment; rather, the Committee’s policy

decisions must be informed by assessments of the maximum level of employment, recognizing that

such assessments are necessarily uncertain and subject to revision. The Committee considers a

wide range of indicators in making these assessments. Information about Committee participants’

estimates of the longer-run normal rates of output growth and unemployment is published four

times per year in the FOMC’s Summary of Economic Projections. For example, in the most

recent projections, the median of FOMC participants’ estimates of the longer-run normal rate of

unemployment was 4.6percent.

In setting monetary policy, the Committee seeks to mitigate deviations of ination from its

longer-run goal and deviations of employment from the Committee’s assessments of its maximum

level. These objectives are generally complementary. However, under circumstances in which the

Committee judges that the objectives are not complementary, it follows a balanced approach in

promoting them, taking into account the magnitude of the deviations and the potentially dierent

time horizons over which employment and ination are projected to return to levels judged

consistent with its mandate.

The Committee intends to rearm these principles and to make adjustments as appropriate at its

annual organizational meeting each January.

statement on Longer-run goaLs and monetary PoLicy strategy

contents

Note: This report reects information that was publicly available as of noon EDT on July12, 2018.

Unless otherwise stated, the time series in the gures extend through, for daily data, July11, 2018; for monthly data,

June2018; and, for quarterly data, 2018:Q1. In bar charts, except as noted, the change for a given period is measured to

its nal quarter from the nal quarter of the preceding period.

For gures 16 and 34, note that the S&P 500 Index and the Dow Jones Bank Index are products of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC and/or its afliates and

have been licensed for use by the Board. Copyright © 2018 S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, a division of S&P Global, and/or its afliates. All rights reserved.

Redistribution, reproduction, and/or photocopying in whole or in part are prohibited without written permission of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC. For more

information on any of S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC’s indices please visit www.spdji.com. S&P® is a registered trademark of Standard & Poor’s Financial

Services LLC, and Dow Jones® is a registered trademark of Dow Jones Trademark Holdings LLC. Neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark

Holdings LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors make any representation or warranty, express or implied, as to the ability of any index to

accurately represent the asset class or market sector that it purports to represent, and neither S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC, Dow Jones Trademark Holdings

LLC, their afliates nor their third party licensors shall have any liability for any errors, omissions, or interruptions of any index or the data included therein.

For gure A in the box “Interest on Reserves and Its Importance for Monetary Policy,” note that neither DTCC Solutions LLC nor any of its afliates shall

be responsible for any errors or omissions in any DTCC data included in this publication, regardless of the cause and, in no event, shall DTCC or any of

its afliates be liable for any direct, indirect, special or consequential damages, costs, expenses, legal fees, or losses (including lost income or lost prot,

trading losses and opportunity costs) in connection with this publication.

Summary ..................................................1

Economic and Financial Developments ......................................... 1

Monetary Policy

........................................................... 2

Special Topics

............................................................. 2

Part 1: Recent Economic and Financial Developments ................ 5

Domestic Developments. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Financial Developments

.................................................... 23

International Developments

................................................. 30

Part 2: Monetary Policy ....................................... 35

Part 3: Summary of Economic Projections ......................... 47

The Outlook for Economic Activity ............................................ 48

The Outlook for Ination

................................................... 50

Appropriate Monetary Policy

................................................ 51

Uncertainty and Risks

...................................................... 51

Abbreviations ..............................................63

List of Boxes

The Labor Force Participation Rate for Prime-Age Individuals ......................... 8

The Recent Rise in Oil Prices

................................................ 16

Developments Related to Financial Stability

..................................... 26

Complexities of Monetary Policy Rules

......................................... 37

Interest on Reserves and Its Importance for Monetary Policy

......................... 44

Forecast Uncertainty

....................................................... 62

1

summary

Economic activity increased at a solid pace

over the rst half of 2018, and the labor

market has continued to strengthen. Ination

has moved up, and in May, the most recent

period for which data are available, ination

measured on a 12-month basis was a little

above the Federal Open Market Committee’s

(FOMC) longer-run objective of 2percent,

boosted by a sizable increase in energy prices.

In this economic environment, the Committee

judged that current and prospective economic

conditions called for a further gradual removal

of monetary policy accommodation. In line

with that judgment, the FOMC raised the

target for the federal funds rate twice in the

rst half of 2018, bringing it to a range of

1¾to 2percent.

Economic and Financial

Developments

The labor market. The labor market has

continued to strengthen. Over the rst

six months of 2018, payrolls increased an

average of 215,000 per month, which is

somewhat above the average pace of 180,000

per month in 2017 and is considerably faster

than what is needed, on average, to provide

jobs for new entrants into the labor force.

The unemployment rate edged down from

4.1percent in December to 4.0percent in June,

which is about ½percentage point below the

median of FOMC participants’ estimates of

its longer-run normal level. Other measures

of labor utilization were consistent with a

tight labor market. However, hourly labor

compensation growth has been moderate,

likely held down in part by the weak pace of

productivity growth in recent years.

Ination. Consumer price ination, as

measured by the 12-month percentage change

in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures, moved up from a little below

the FOMC’s objective of 2percent at the end

of last year to 2.3percent in May, boosted by

a sizable increase in consumer energy prices.

The 12-month measure of ination that

excludes food and energy items (so-called core

ination), which historically has been a better

indicator of where overall ination will be in

the future than the total gure, was 2percent

in May. This reading was ½percentage point

above where it had been 12 months earlier, as

the unusually low readings from last year were

not repeated. Measures of longer-run ination

expectations have been generally stable.

Economic growth. Real gross domestic product

(GDP) is reported to have increased at an

annual rate of 2percent in the rst quarter

of 2018, and recent indicators suggest that

economic growth stepped up in the second

quarter. Gains in consumer spending slowed

early in the year, but they rebounded in

the spring, supported by strong job gains,

recent and past increases in household

wealth, favorable consumer sentiment, and

higher disposable income due in part to the

implementation of the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act.

Business investment growth has remained

robust, and indexes of business sentiment have

been strong. Foreign economic growth has

remained solid, and net exports had a roughly

neutral eect on real U.S. GDP growth in the

rst quarter. However, activity in the housing

market has leveled o this year.

Financial conditions. Domestic nancial

conditions for businesses and households

have generally continued to support economic

growth. After rising steadily through 2017,

broad measures of equity prices are modestly

higher, on balance, from their levels at the end

of last year amid some bouts of heightened

volatility in nancial markets. While long-

term Treasury yields, mortgage rates, and

yields on corporate bonds have risen so far

this year, longer-term interest rates remain

low by historical standards, and corporate

bond issuance has continued at a moderate

pace. Moreover, most types of consumer loans

2 SUMMARY

remained widely available for households with

strong creditworthiness, and credit provided by

commercial banks continued to expand. The

foreign exchange value of the U.S. dollar has

appreciated somewhat against the currencies

of our trading partners this year, but it

remains below its level at the start of 2017.

Foreign nancial conditions remain generally

supportive of growth despite recent increases

in nancial stress in several emerging market

economies.

Financial stability. The U.S. nancial system

remains substantially more resilient than

during the decade before the nancial crisis.

Asset valuations continue to be elevated

despite declines since the end of 2017 in the

forward price-to-earnings ratio of equities and

the prices of corporate bonds. In the private

nonnancial sector, borrowing among highly

levered and lower-rated businesses remains

elevated, although the ratio of household

debt to disposable income continues to be

moderate. Vulnerabilities stemming from

leverage in the nancial sector remain low,

reecting in part strong capital positions

at banks, whereas some measures of hedge

fund leverage have increased. Vulnerabilities

associated with maturity and liquidity

transformation among banks, insurance

companies, money market mutual funds,

and asset managers remain below levels that

generally prevailed before2008.

Monetary Policy

Interest rate policy. Over the rst half of 2018,

the FOMC has continued to gradually increase

the target range for the federal funds rate.

Specically, the Committee decided to raise

the target range for the federal funds rate at

its meetings in March and June, bringing it

to the current range of 1¾ to 2percent. The

decisions to increase the target range for the

federal funds rate reected the economy’s

continued progress toward the Committee’s

objectives of maximum employment and price

stability. Even with these policy rate increases,

the stance of monetary policy remains

accommodative, thereby supporting strong

labor market conditions and a sustained return

to 2percent ination.

The FOMC expects that further gradual

increases in the target range for the federal

funds rate will be consistent with a sustained

expansion of economic activity, strong labor

market conditions, and ination near the

Committee’s symmetric 2percent objective

over the medium term. Consistent with this

outlook, in the most recent Summary of

Economic Projections (SEP), which was

compiled at the time of the June FOMC

meeting, the median of participants’

assessments for the appropriate level for

the federal funds rate rises gradually over

the period from 2018 to 2020 and stands

somewhat above the median projection for

its longer-run level by the end of 2019 and

through 2020. (The June SEP is presented

in Part 3 of this report.) However, as the

Committee has continued to emphasize, the

timing and size of future adjustments to the

target range for the federal funds rate will

depend on the Committee’s assessment of

realized and expected economic conditions

relative to its maximum-employment objective

and its symmetric 2percent ination objective.

Balance sheet policy. The FOMC has

continued to implement the balance sheet

normalization program described in the

Addendum to the Policy Normalization

Principles and Plans that the Committee issued

about a year ago. Specically, the FOMC has

been reducing its holdings of Treasury and

agency securities by decreasing, in a gradual

and predictable manner, the reinvestment

of principal payments it receives from these

securities.

Special Topics

Prime-age labor force participation. Labor

force participation rates (LFPRs) for men and

women between 25 and 54years old—that is,

the share of these individuals either working

or actively seeking work—trended lower

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 3

between 2000 and 2013. Those trends likely

reect numerous factors, including a long-run

decline in the demand for workers with lower

levels of education and an increase in the

share of the population with some form of

disability. By contrast, the prime-age LFPR

has increased notably since 2013, and the

share of nonparticipants who report wanting

a job remains above pre-recession levels. Thus,

some continuation of the recent increase in

the prime-age LFPR may be possible if labor

demand remains strong. (See the box “The

Labor Force Participation Rate for Prime-Age

Individuals” in Part 1.)

Oil prices. Oil prices have climbed rapidly

over the past year, reecting both supply and

demand factors. Although higher oil prices

are likely to restrain household consumption

in the United States, much of the negative

eect on GDP from lower consumer spending

is likely to be oset by increased production

and investment in the growing U.S. oil sector.

Consequently, higher oil prices now imply

much less of a net overall drag on the economy

than they did in the past, although they will

continue to have important distributional

eects. The negative eect of upward moves

in oil prices should get smaller still as U.S. oil

production grows and net oil imports decline

further. (See the box “The Recent Rise in Oil

Prices” in Part 1.)

Monetary policy rules. Monetary policymakers

consider a wide range of information on

current economic conditions and the outlook

when deciding on a policy stance they deem

most likely to foster the FOMC’s statutory

mandate of maximum employment and stable

prices. They also routinely consult monetary

policy rules that connect prescriptions for the

policy interest rate with variables associated

with the dual mandate. The use of such rules

requires, among other considerations, careful

judgments about the choice and measurement

of the inputs into the rules such as estimates

of the neutral interest rate, which are highly

uncertain. (See the box “Complexities of

Monetary Policy Rules” in Part 2.)

Interest on reserves. The payment of interest

on reserves—balances held by banks in

their accounts at the Federal Reserve—is an

essential tool for implementing monetary

policy because it helps anchor the federal

funds rate within the FOMC’s target range.

This tool has permitted the FOMC to achieve

a gradual increase in the federal funds rate in

combination with a gradual reduction in the

Fed’s securities holdings and in the supply

of reserve balances. The FOMC judged that

removing monetary policy accommodation

through rst raising the federal funds rate

and then beginning to shrink the balance

sheet would best contribute to achieving and

maintaining maximum employment and

price stability without causing dislocations in

nancial markets or institutions that could put

the economic expansion at risk. (See the box

“Interest on Reserves and Its Importance for

Monetary Policy” in Part 2.)

5

Domestic Developments

The labor market strengthened further

during the rst half of the year . . .

Labor market conditions have continued to

strengthen so far in 2018. According to the

Bureau of Labor Statistics (BLS), gains in

total nonfarm payroll employment averaged

215,000 per month over the rst half of the

year. That pace is up from the average monthly

pace of job gains in 2017 and is considerably

faster than what is needed to provide jobs for

new entrants into the labor force (gure1).

1

Indeed, the unemployment rate edged down

from 4.1percent in December to 4.0percent

in June (gure2). This rate is below all

Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC)

participants’ estimates of its longer-run

normal level and is about ½percentage point

below the median of those estimates.

2

The

unemployment rate in June is close to the lows

last reached in 2000.

The labor force participation rate (LFPR),

which is the share of individuals aged 16

and older who are either working or actively

looking for work, was 62.9percent in June

and has changed little, on net, since late

2013 (gure3). The aging of the population

is an important contributor to a downward

trend in the overall participation rate. In

particular, members of the baby-boom

cohort are increasingly moving into their

retirement years, a time when labor force

participation is typically low. Indeed, the

share of the civilian population aged 65

and over in the United States climbed from

16percent in 2000 to 19percent in 2017 and

is projected to rise to 24percent by 2026.

Given this trend, the at trajectory of the

1. Monthly job gains in the range of 130,000 to

160,000 are consistent with an unchanged unemployment

rate and an unchanged labor force participation rate.

2. See the Summary of Economic Projections in Part3

of this report.

Part 1

recent economic and financiaL deveLoPments

Total nonfarm

800

600

400

200

+

_

0

200

400

Thousands of jobs

2018201720162015201420132012201120102009

1. Net change in payroll employment

3-month moving averages

Private

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

6 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

LFPR during the past few years is consistent

with strengthening labor market conditions.

Similarly, the LFPR for individuals between

25 and 54years old—which is much less

sensitive to population aging—has been rising

for the past several years. (The box “The

Labor Force Participation Rate for Prime-

Age Individuals” examines the prospects for

further increases in participation for these

individuals.) The employment-to-population

ratio for individuals 16 and over—the share

of the total population who are working—

was 60.4percent in June and has been

gradually increasing since 2011, reecting the

combination of the declining unemployment

rate and the at LFPR.

Other indicators are also consistent with

a strong labor market. As reported in the

Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey

(JOLTS), the rate of job openings has

remained quite elevated.

3

The rate of quits has

3. Indeed, the number of job openings now about

matches the number of unemployed individuals.

Employment-to-population ratio

Prime-age labor force

participation rate

56

58

60

62

64

66

68

Percent

80

81

82

83

84

85

20182015201220092006

3. Labor force participation rates and

employment-to-population ratio

Percent

Labor force participation rate

NOTE: The data are monthly. The prime-age labor force participation

rate

is a percentage of the population aged 25 to 54. The labor force

participation

rate and the employment-to-population ratio are percentages of the

population

aged 16 and over.

SOURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

U-5

U-4

U-6

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

2. Measures of labor underutilization

Monthly

Unemployment rate

N

OTE

: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. U-4 measures total unemployed plus discouraged workers, as

a

percentage of the labor force plus discouraged workers. Discouraged workers are a subset of marginally attached workers who are not currently looking for work

because they believe no jobs are available for them. U-5 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached to the labor force, as a percentage of the

labor

force plus persons marginally attached to the labor force. Marginally attached workers are not in the labor force, want and are

available for work, and have looked

for a job in the past 12 months. U-6 measures total unemployed plus all marginally attached workers plus total employed part time for economic reasons, as

a

percentage of the labor force plus all marginally attached workers. The shaded bar indicates a period of business recession as defined by the National Bureau

of

Economic Research.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 7

stayed high in the JOLTS, an indication that

workers are able to successfully switch jobs

when they wish to. In addition, the JOLTS

layo rate has been low, and the number of

people ling initial claims for unemployment

insurance benets has remained near its

lowest level in decades. Other survey evidence

indicates that households perceive jobs as

plentiful and that businesses see vacancies as

hard to ll. Another indicator, the share of

workers who are working part time but would

prefer to be employed full time—which is part

of the U-6 measure of labor underutilization

from the BLS—fell further in the rst six

months of the year and now stands close to its

pre-recession level (as shown in gure2).

. . . and unemployment rates have fallen

for all major demographic groups

The continued decline in the unemployment

rate has been reected in the experiences of

multiple racial and ethnic groups (gure4).

The unemployment rates for blacks or

African Americans and Hispanics tend to

rise considerably more than rates for whites

and Asians during recessions but decline

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

4. Unemployment rate by race and ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE: Unemployment rate measures total unemployed as a percentage of the labor force. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or Latino may be of

any race. The shaded bar indicates a period of business recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

8 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

increases in automation, such as the use of robotics,

and various aspects of globalization have spurred

the elimination of some types of jobs—in particular,

some manufacturing jobs that have historically been

held by workers without a college education—and

emerging jobs may require a different set of skills. These

developments may have led some workers to become

discouraged over the lack of suitable job opportunities

and drop out of the labor force.

1

The rising share of

college-educated workers, which may partly reect

individuals responding over time to the declining

demand for jobs that require less education, has likely

prevented even steeper declines in the prime-age LFPR,

as better-educated workers have higher LFPRs and

may be more adaptable to unforeseen disruptions in

particular jobs or industries.

Another potential factor may be that an increasing

share of the prime-age population has some difculty

working because of physical or mental disabilities.

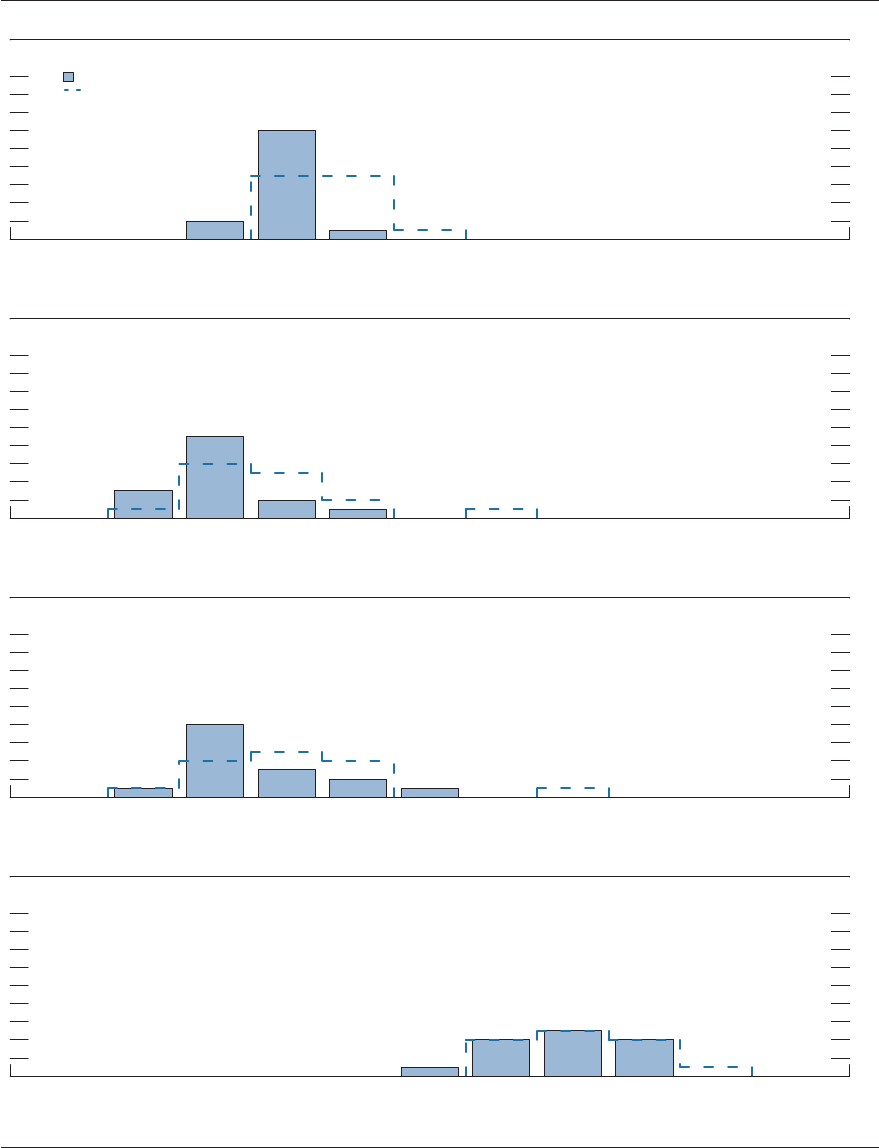

For example, gure C shows that about 5percent of

both prime-age men and women report that they are

out of the labor force and do not want a job due to

disability or illness; those shares have trended higher

over the past several decades. Other research suggests

that increased opioid use may be associated with a

lower prime-age LFPR, although it is unclear how

much of the decline in the prime-age LFPR can be

directly explained by opioid use or whether increases

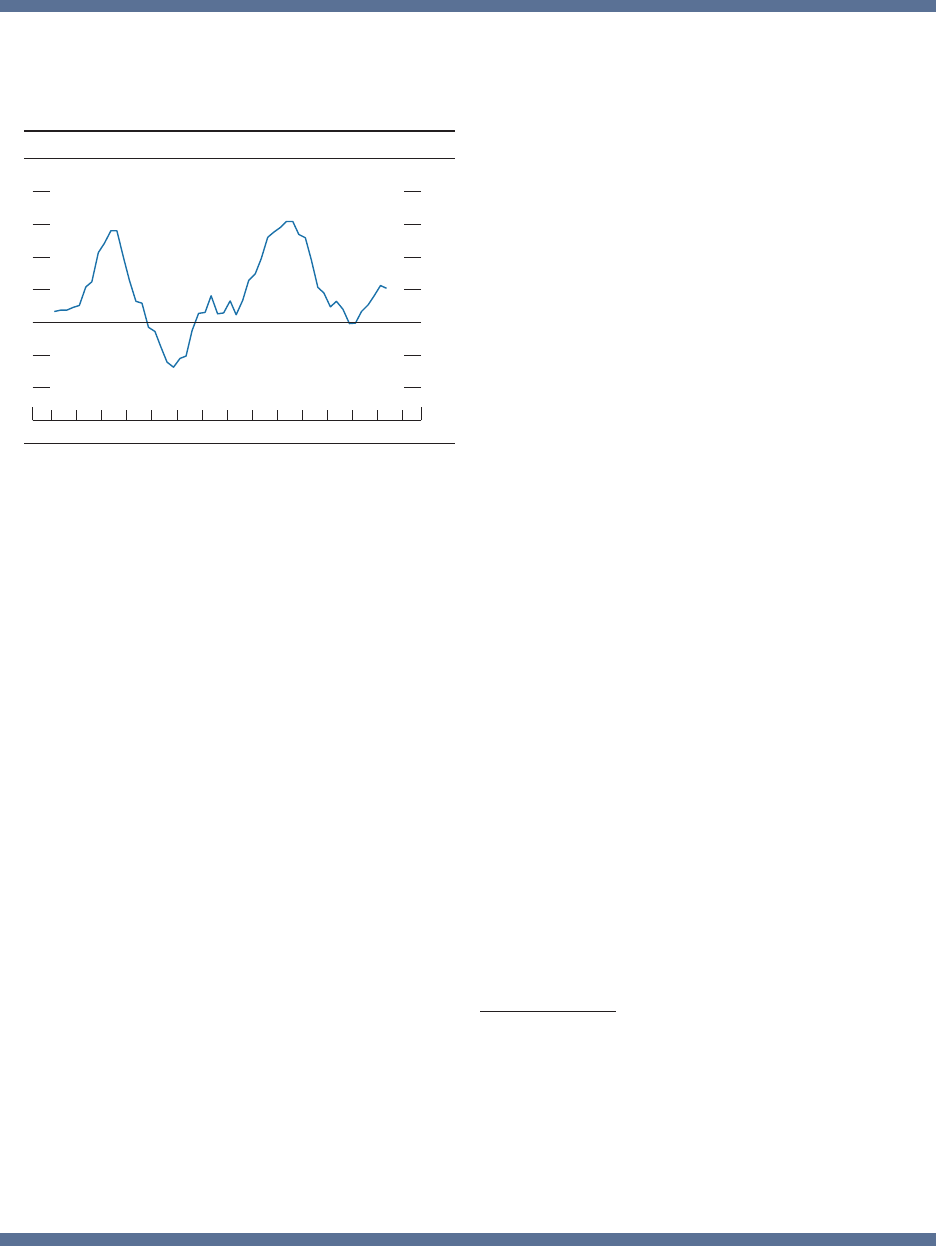

The overall labor force participation rate (LFPR) has

generally been trending lower since 2000, and while

the aging of the baby-boom generation into retirement

ages provides an important reason for that decline,

it is not the only reason. Another contributing factor,

as shown in gureA, is that the LFPRs of prime-age

men and women (those between 25 and 54years

old) trended lower through 2013 even though prime-

age LFPRs are largely unaffected by the aging of

the population: The prime-age male LFPR has been

declining for six decades, and the prime-age female

LFPR has drifted lower since 2000 after a multidecade

increase. Nevertheless, prime-age LFPRs have moved

up notably and consistently since 2013, as improving

labor market conditions have drawn some individuals

back into the labor force and encouraged others not to

leave. These recent increases in the prime-age LFPR,

in the context of the longer-run trend decline, raise the

question of how much additional scope there is for

further increases in prime-age labor force participation.

To gauge whether further increases are possible, a

useful starting point is understanding the factors behind

the longer-run decline in the prime-age LFPR, as these

factors may limit additional increases if they continue

to exert some downward pressure. One factor may

be a secular decline in the demand for workers with

lower levels of education. Indeed, as shown in gureB,

the long-run declines in prime-age LFPR are much

larger among adults without a college degree than

among college-educated adults. Research suggests that

The Labor Force Participation Rate for Prime-Age Individuals

Men

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

90

95

Percent

201820132008200319981993198819831978

A. Prime-age labor force participation rates

Monthly

Women

N

OTE: The data are seasonally adjusted. The shaded bars indicate

periods

of

business recession as defined by the National Bureau of

Economic

Research.

S

OURCE: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

1. For evidence on displacement from technological

changes, see David H. Autor, David Dorn, and Gordon H.

Hanson (2015), “Untangling Trade and Technology: Evidence

from Local Labor Markets,” Economic Journal, vol.125 (May),

pp. 621–46; Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo (2017),

“Robots and Jobs: Evidence from U.S. Labor Markets,” NBER

Working Paper Series 23285 (Cambridge, Mass.: National

Bureau of Economic Research, March), www.nber.org/

papers/w23285; and Daron Acemoglu and Pascual Restrepo

(2018), “Articial Intelligence, Automation, and Work,” NBER

Working Paper Series 24196 (Cambridge, Mass.: National

Bureau of Economic Research, January), www.nber.org/

papers/w24196. For evidence on globalization—in particular,

import competition since the 2000s—see David H. Autor,

David Dorn, and Gordon H. Hanson (2013), “The China

Syndrome: Local Labor Market Effects of Import Competition

in the United States,” American Economic Review, vol. 103

(October), pp. 2121–68. A discussion of these and other

explanations is also provided in Katharine G. Abraham and

Melissa S. Kearney (2018), “Explaining the Decline in the U.S.

Employment-to-Population Ratio: A Review of the Evidence,”

NBER Working Paper Series 24333 (Cambridge, Mass.:

National Bureau of Economic Research, February), www.nber.

org/papers/w24333.

(continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 9

responsibilities as women participate in the workforce

in greater numbers. For some—especially those for

whom childcare costs are not a major concern—not

participating in the labor force may represent an

unconstrained choice to care for other members of their

families. For others, however, this decision may reect

a lack of affordable childcare.

Additionally, the share of the population—

particularly black men—with a history of incarceration

has increased over time. Individuals who have

previously been incarcerated often have trouble nding

work, in part because many employers choose not to

hire people with such a background and likely also

in part because incarceration prevents people from

accumulating work experience and developing skills

valuable to employers. Discrimination could also help

explain the lack of participation for some minority

groups, as they recognize that such discrimination

limits their job opportunities.

International comparisons may help clarify the

importance of some of those factors. Since 1990, the

in opioid use are an indirect result of poor employment

opportunities.

2

Caregiving responsibilities play an important role in

explaining why LFPRs for prime-age women are lower

than for men, and they may play an increasing role in

explaining declining prime-age LFPRs for men as well.

As shown in gure C, roughly 15percent of prime-

age women report being out of the labor force for

caregiving reasons—by far the largest reason for prime-

age women to report not wanting a job—but this share

has been fairly at over time. In contrast, while a much

smaller fraction of men are out of the labor force for

caregiving reasons, that share has trended up in recent

decades, likely reecting some shift in household

2. Evidence that opioid use could be signicant for

understanding the declining LFPR is provided by Alan B.

Krueger (2017), “Where Have All the Workers Gone? An

Inquiry into the Decline of the U.S. Labor Force Participation

Rate,” Brookings Papers on Economic Activity, Fall, pp. 1–82,

https://www.brookings.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/02/

kruegertextfa17bpea.pdf, while little relationship between

opioid prescriptions and employment at the county level is

found in Janet Currie, Jonas Y. Jin, and Molly Schnell (2018),

“U.S. Employment and Opioids: Is There a Connection?”

NBER Working Paper Series 24440 (Cambridge, Mass.:

National Bureau of Economic Research, March), www.nber.

org/papers/w24440. Some evidence on whether the opioid

epidemic varies with local economic conditions is provided

by Jeff Larrimore, Alex Durante, Kimberly Kreiss, Ellen Merry,

Women

Men

B. Prime-age labor force participation rates by education

N: The data are seasonally adjusted 12-month moving averages and extend through May 2018. The shaded bars indicate

periods of business recession as dened by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

S: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

Monthly PercentMonthly Percent

Bachelor's degree

High school degree or less 82

86

90

94

98

201820132008200319981993198819831978

Some college

Bachelor's degree

High school degree or less

50

55

60

65

70

75

80

85

201820132008200319981993198819831978

Some college

Christina Park, and Claudia Sahm (2018), “Shedding Light on

Our Economic and Financial Lives,” FEDS Notes, https://www.

federalreserve.gov/econres/notes/feds-notes/shedding-light-on-

our-economic-and-nancial-lives-20180522.htm.

(continued on next page)

10 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

self-report as wanting a job (despite not having actively

searched for a job recently) has been declining since

2010, that share for men remains between ¼ and

½percentage point above its 2007 level and earlier

expansion peaks. Furthermore, prime-age men and

women who had previously reported being out of the

labor force and not wanting a job due to disability or

illness have been entering the labor force at increasing

rates in recent years.

Looking forward, how can policymakers support

additional improvements in the prime-age LFPR?

Favorable labor market conditions can likely help,

and monetary policy can therefore play a role through

supporting strong cyclical conditions as part of its

maximum-employment objective. However, structural

factors (in contrast with cyclical ones) are also

important to address; policies to address such factors

are beyond the scope of monetary policy.

prime-age LFPR in the United States has declined

considerably for both men and women relative to other

advanced countries. Some factors, like automation and

globalization, have affected all advanced economies to

some degree and for some time, yet diverging long-run

trends in prime-age labor force participation have still

occurred. Research suggests that part of the relative

decline in the United States is explained by differential

changes in work-family policies across countries.

Other parts of the divergence may be explained by

other policies, including policies designed toward

keeping those affected by automation and globalization

attached to the labor force, or other factors—such as

incarceration or opioid use—that differ across those

countries.

3

Although many of the factors behind the

multidecade decline in the prime-age LFPR may

persist, some continuation of the increases in the LFPR

over the past few years nevertheless seems possible,

especially if labor market conditions remain favorable.

Indeed, as shown in gure C, although the share of

nonparticipating prime-age men and women who

3. For recent trends on prime-age LFPRs in the United

States compared with other developed countries, see

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development

(2018), OECD Economic Surveys: United States 2018 (Paris:

OECD Publishing), dx.doi.org/10.1787/eco_surveys-usa-2018-

en. For a description of policy differences across countries

Disabled

Caregiving

Wants job

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

2018201420102006200219981994

Other, does not want job

Disabled

Caregiving

Wants job

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

2018201420102006200219981994

Other, does not want job

PercentMonthly Monthly Percent

N: The data are seasonally adjusted 12-month moving averages and extend through May 2018. The shaded bars indicate

periods of business recession as dened by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

S: U.S. Census Bureau, Current Population Survey.

Women

Men

C. Prime-age nonparticipation by reason

The Labor Force Participation Rate (continued)

and how this may affect differences in LFPR, see International

Monetary Fund (2018), “Labor Force Participation in Advanced

Economies: Drivers and Prospects,” chapter 2 in World

Economic Outlook: Cyclical Upswing, Structural Change

(Washington: IMF, April), pp.71–128. For evidence on how

work-family policies may affect prime-age LFPRs in the United

States relative to other OECD countries, see Francine D. Blau

and LawrenceM. Kahn (2013), “Female Labor Supply: Why

Is the United States Falling Behind?” American Economic

Review, vol. 103 (May), pp. 251–56.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 11

more rapidly during expansions. Indeed,

the declines in the unemployment rates for

blacks and Hispanics have been particularly

striking, and the rates have recently been at

or near their lowest readings since these series

began in the early 1970s. Although dierences

in unemployment rates across ethnic and

racial groups have narrowed in recent years,

they remain substantial and similar to pre-

recession levels. The rise in LFPRs for prime-

age individuals over the past few years has

also been evident in each of these racial and

ethnic groups, with increases again particularly

notable for African Americans. Even so, the

LFPR for whites remains higher than that for

the other groups (gure5).

4

Increases in labor compensation have

been moderate . . .

Despite the strong labor market, the available

indicators generally suggest that increases

in hourly labor compensation have been

moderate. Compensation per hour in the

business sector—a broad-based measure

of wages, salaries, and benets that is quite

volatile—rose 2¾percent over the four

quarters ending in 2018:Q1, slightly more than

the average annual increase over the preceding

seven or so years (gure6). The employment

cost index—a less volatile measure of both

wages and the cost to employers of providing

benets—likewise was 2¾percent higher in

the rst quarter of 2018 relative to its year-

earlier level; this increase was ½percentage

point faster than its gain a year earlier. Among

measures that do not account for benets,

average hourly earnings rose 2¾percent in

June relative to 12months earlier, a gain in

line with the average increase in the preceding

few years. According to the Federal Reserve

Bank of Atlanta, the median 12-month wage

4. The lower levels of labor force participation for

these other groups dier importantly by sex. For African

Americans, men have a lower participation rate relative

to white men, while the participation rate for African

American women is as high as that of white women. By

contrast, the lower LFPRs for Hispanics and Asians

reect lower participation among women.

Employment cost index

Atlanta Fed's

Wage Growth Tracker

Average hourly earnings

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent change from year earlier

20182016201420122010

6. Measures of change in hourly compensation

Compensation per hour,

business sector

N

OTE

: Business-sector compensation is on a 4-quarter percentage

change

basis. For the employment cost index, change is over the 12 months ending in

the last month of each quarter; for average hourly earnings, change is from

12

months earlier; for the Atlanta Fed's Wage Growth Tracker, the data

are

shown as a 3-month moving average of the 12-month percent change

and

extend through May 2018.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics; Federal

Reserve

Bank of Atlanta, Wage Growth Tracker.

Black or African American

Asian

Hispanic or Latino

76

77

78

79

80

81

82

83

84

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

5. Prime-age labor force participation rate by race and

ethnicity

Monthly

White

N

OTE

: The prime-age labor force participation rate is a percentage of the

population aged 25 to 54. Persons whose ethnicity is identified as Hispanic or

Latino may be of any race. The data are seasonally adjusted by Board staff

and are 3-month moving averages. The shaded bar indicates a period of

business recession as defined by the National Bureau of Economic Research.

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics.

12 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

growth of individuals reporting to the Current

Population Survey increased about 3¼percent

in May, also similar to its readings from the

past few years.

5

. . . and likely have been restrained by

slow growth of labor productivity

Those moderate rates of compensation

gains likely reect the osetting inuences

of a strong labor market and persistently

weak productivity growth. Since 2008, labor

productivity has increased only a little more

than 1percent per year, on average, well below

the average pace from 1996 through 2007 of

2.8percent and also below the average gain in

the 1974–95 period of 1.6percent (gure7).

The weakness in productivity growth may

be partly attributable to the sharp pullback

in capital investment during the most recent

recession and the relatively slow recovery

that followed. However, considerable debate

remains about the reasons for the recent

slowdown in productivity growth and whether

it will persist.

6

Price ination has picked up from the

low readings in 2017

In 2017, ination remained below the FOMC’s

longer-run objective of 2percent. Partly

because the softness in some price categories

appeared idiosyncratic, Federal Reserve

policymakers expected ination to move

higher in 2018.

7

This expectation appears to be

5. The Atlanta Fed’s measure diers from others in

that it measures the wage growth only of workers who

were employed both in the current survey month and

12months earlier.

6. The box “Productivity Developments in the

Advanced Economies” in the July2017 Monetary

Policy Report provides more information. See Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2017),

Monetary Policy Report (Washington: Board of

Governors, July), pp. 12–13, https://www.federalreserve.

gov/monetarypolicy/2017-07-mpr-part1.htm.

7. Additional details can be found in the June2017

Summary of Economic Projections, an addendum to the

minutes of the June2017 FOMC meeting. See Board

of Governors of the Federal Reserve System (2017),

“Minutes of the Federal Open Market Committee,

1

2

3

4

Percent, annual rate

7. Change in business-sector output per hour

1948–

73

1974–

95

1996–

2000

2001–

07

2008–

present

NOTE

: Changes are measured from Q4 of the year immediately

preceding

the period through Q4 of the final year of the period. The final period

is

measured from 2007:Q4 through 2018:Q1.

SOURCE

: Bureau of Labor Statistics via Haver Analytics.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 13

on track so far. Consumer price ination, as

measured by the 12-month percentage change

in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures (PCE), moved up to 2.3percent

in May (gure8). Core PCE ination, which

excludes consumer food and energy prices that

are often quite volatile and typically provides

a better indication than the total measure of

where overall ination will be in the future,

was 2percent over the 12months ending in

May—0.5percentage point higher than it

had been one year earlier. The total measure

exceeded core ination because of a sizable

increase in consumer energy prices. In

contrast, food price ination has continued to

be low by historical standards—data through

May show the PCE price index for food and

beverages having increased less than ½percent

over the past year.

The higher readings in both total and core

ination relative to a year earlier reect faster

price increases for a wide range of goods and

services this year and the dropping out of the

12-month calculation of the steep one-month

decline in the price index for wireless telephone

services in March last year. The 12-month

change in the trimmed mean PCE price

index—an alternative indicator of underlying

ination produced by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Dallas that may be less sensitive

than the core index to idiosyncratic price

movements—slowed by less than core ination

over 2017 and has also increased a bit less

this year. This index rose 1.8percent over the

12months ending in May, up a touch from the

increase over the same period last year.

8

June13–14, 2017,” press release, July5, https://

www.federalreserve.gov/newsevents/pressreleases/

monetary20170705a.htm.

8. The trimmed mean index excludes whatever prices

showed the largest increases or decreases in a given

month; for example, the sharp decline in prices for

wireless telephone services in March2017 was excluded

from this index.

Excluding food

and energy

Trimmed mean

+

_

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

12-month percent change

20182017201620152014201320122011

8. Change in the price index for personal consumption

expenditures

Monthly

Total

NOTE

: The data extend through May 2018; changes are from one year

earlier.

SOURCE: For trimmed mean, Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas; for all else,

Bureau of Economic Analysis; all via Haver Analytics.

14 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Oil prices have surged amid supply

concerns . . .

As noted, the faster pace of total ination

this year relative to core ination reects a

substantial rise in consumer energy prices.

Retail gasoline prices this year were driven

higher by a rise in oil prices. The spot price of

Brent crude oil rose from about $65 per barrel

in December to around $75per barrel in early

July (gure9). Although that increase took

place against a backdrop of continued strength

in global demand, supply concerns have

become more prevalent in recent months. (For

a discussion of the reasons behind the oil price

increases along with a review of the eects of

oil prices on U.S. economic growth, see the

box “The Recent Rise in Oil Prices.”)

. . . while prices of imports other than

energy have also increased

Nonfuel import prices rose sharply in early

2018, partly reecting the pass-through

of earlier increases in commodity prices

(gure10). In particular, metals prices posted

sizable gains late last year due to strong

global demand but have retreated somewhat

in recent weeks.

Survey-based measures of ination

expectations have been stable . . .

Expectations of ination likely inuence actual

ination by aecting wage- and price-setting

decisions. Survey-based measures of ination

expectations at medium- and longer-term

horizons have remained generally stable so

far this year. In the Survey of Professional

Forecasters conducted by the Federal Reserve

Bank of Philadelphia, the median expectation

for the annual rate of increase in the PCE

price index over the next 10years has been

around 2percent for the past several years

(gure11). In the University of Michigan

Surveys of Consumers, the median value

for ination expectations over the next 5 to

10years has been about 2½percent since

the end of 2016, though this level is about

¼percentage point lower than had prevailed

through 2014. In contrast, in the Survey of

Consumer Expectations conducted by the

Nonfuel import prices

94

96

98

100

102

July 2014 = 100

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

2018201720162015201420132012

10. Nonfuel import prices and industrial metals indexes

July 2014 = 100

Industrial metals

N

OTE

: The data for nonfuel import prices are monthly and extend through

May

2018. The data for industrial metals are a monthly average of daily data

and extend through June 29, 2018.

SOURCE

: For nonfuel import prices, Bureau of Labor Statistics; for

industrial

metals, S&P GSCI Industrial Metals Spot Index via Haver

Analytics.

Spot price

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

120

130

Dollars per barrel

2013 2014 2015 2016 2017 2018

9. Brent spot and futures prices

Weekly

24-month-ahead

futures contracts

N

OTE: The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend

through

July 11, 2018.

S

OURCE: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 15

Federal Reserve Bank of New York, the

median of respondents’ expected ination rate

three years hence has been moving up recently

and is currently at the top of the range it has

occupied over the past couple of years.

. . . while market-based measures of

ination compensation have largely

moved sideways this year

Ination expectations can also be gauged

by market-based measures of ination

compensation. However, the inference

is not straightforward, because market-

based measures can be importantly aected

by changes in premiums that provide

compensation for bearing ination and

liquidity risks. Measures of longer-term

ination compensation—derived either from

dierences between yields on nominal Treasury

securities and those on comparable-maturity

Treasury Ination-Protected Securities

(TIPS) or from ination swaps—have moved

sideways for the most part this year after

having returned to levels seen in early 2017

(gure12).

9

The TIPS-based measure of

5-to-10-year-forward ination compensation

and the analogous measure of ination swaps

are now about 2percent and 2½percent,

respectively, with both measures below the

ranges that persisted for most of the 10years

before the start of the notable declines in

mid-2014.

10

9. Ination compensation implied by the TIPS

breakeven ination rate is based on the dierence, at

comparable maturities, between yields on nominal

Treasury securities and yields on TIPS, which are indexed

to the total consumer price index (CPI). Ination swaps

are contracts in which one party makes payments of

certain xed nominal amounts in exchange for cash

ows that are indexed to cumulative CPI ination over

some horizon. Focusing on ination compensation 5 to

10years ahead is useful, particularly for monetary policy,

because such forward measures encompass market

participants’ views about where ination will settle in the

long term after developments inuencing ination in the

short term have run their course.

10. As these measures are based on CPI ination,

one should probably subtract about ¼ to ½percentage

point—the average dierential with PCE ination over

the past two decades—to infer ination compensation on

a PCE basis.

Michigan survey expectations

for next 5 to 10 years

1

2

3

4

Percent

2018201620142012201020082006

SPF expectations

for next 10 years

11. Median inflation expectations

NOTE

: The Michigan survey data are monthly. The SPF data for

inflation

expectations for personal consumption expenditures are quarterly and

extend

from 2007:Q1 through 2018:Q2.

S

OURCE: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers; Federal

Reserve

Bank of Philadelphia, Survey of Professional Forecasters (SPF).

Inflation swaps

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Percent

20182016201420122010

12. 5-to-10-year-forward inflation compensation

Weekly

TIPS breakeven rates

N

OTE:The data are weekly averages of daily data and extend

through

July 6, 2018. TIPS is Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities.

SOURCE: Federal Reserve Bank of New York; Barclays; Federal

Reserve

Board staff estimates.

16 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

the country’s economic and political crisis. Prices also

increased after President Trump announced on May8

that the United States was withdrawing from the Iran

nuclear deal and that sanctions against Iranian oil

exports would be reinstated.

The pattern of spot and futures prices indicates

that market participants generally anticipate that oil

prices will decline slowly over the next few years, in

part reecting an expectation that supply, including

U.S. shale oil production, will grow to meet demand.

In addition, the higher prices put pressure on OPEC’s

November2016 agreement with certain non-OPEC

countries to restrain production. A stated aim of the

agreement was to reduce the glut in global inventories,

and, in recent months, inventory levels have fallen

rapidly toward long-run averages. In response to both

lower inventories and higher prices, OPEC leaders

slightly relaxed the production agreement in June this

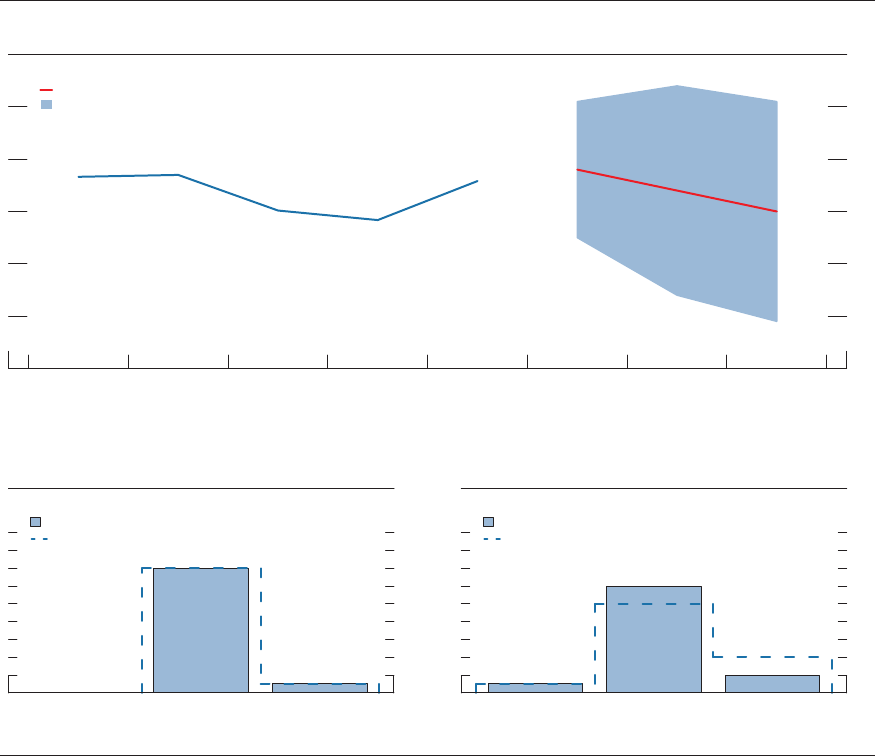

Oil prices have increased more than 50percent

over the past year, with the spot price of Brent crude

oil rising from a bit below $50per barrel to around

$75per barrel (gureA). For much of the period,

further-dated futures prices remained relatively stable,

in the neighborhood of $55per barrel; however, since

February, futures prices have moved up appreciably,

reaching over $70per barrel.

Both supply and demand factors have contributed

to the oil price increase. In particular, the broad-based

improvement in the outlook for the global economy

was a key driver of the price increase in the second

half of 2017. In recent months, supply concerns have

become more prevalent, affecting both spot and further-

dated futures prices. Despite sharply rising U.S. oil

production, markets have been attuned to escalating

conict between Saudi Arabia and Iran as well as the

precipitous decline in Venezuelan oil production amid

The Recent Rise in Oil Prices

Spot price

40

50

60

70

80

90

Dollars per barrel

Jan. Mar. May July Sept. Nov. Jan. Mar. May July

20182017

A. Brent spot and futures prices

Daily

December 2019 futures price

S

OURCE

: ICE Brent Futures via Bloomberg.

(continued)

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 17

power abroad than in the past, as much of the negative

effect on GDP from lower household consumption

is likely to be offset by increased production and

investment in the growing U.S. oil sector. On net, the

drag on GDP from higher oil prices is likely a small

fraction of what it was a decade ago and should get

smaller still if U.S. oil production continues to grow

as projected—gure C—and the net oil import share

shrinks toward zero.

Indeed, if U.S. oil trade moves fully into balance,

the offsetting effects of a change in the relative price of

oil might be expected to net out within the domestic

economy. However, even if the United States is no

longer a net oil importer, to the extent that higher

oil prices cause credit-constrained consumers to cut

spending by more than oil producers expand their

investment, this redistribution of purchasing power

could still have negative effects on overall GDP.

year, reducing some of the upward pressure on prices.

That said, futures prices have not returned to their early

2018 levels, implying that market participants expect

some of the recent increase in prices to be long lasting.

What is the expected effect of the recent rise in oil

prices on the U.S. economy? To begin with, higher oil

prices are likely to restrain household consumption.

In particular, the increase in oil prices since last year

is estimated to have translated into a roughly $300

increase in annual expenditures on gasoline for the

average household, from about $2,100 to $2,400.

However, as U.S. oil production has grown rapidly

over the past decade, the ratio of net U.S. oil imports

to U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) has declined

substantially (gure B). As a result, higher oil prices

now imply much less of a redistribution of purchasing

0

.5

1.0

1.5

2.0

2.5

3.0

3.5

Percent of nominal GDP

2019201720152013201120092007200520032001

B. Net oil import share

Quarterly

NOTE:

The data extending through 2018:Q1 are quarterly averages of daily

oil

futures prices, quarterly averages of monthly oil imports and exports,

and

quarterly

GDP. The data from 2018:Q2 through 2019:Q4 are

projections

based

on quarterly averages of monthly oil futures prices, quarterly

averages

of monthly oil imports and exports, and quarterly GDP.

SOURCE: Department of Energy via Haver Analytics; ICE Brent Futures

via

Bloomberg; Bureau of Economic Analysis; staff calculations.

8

9

10

11

12

13

Million barrels per day

201920182017201620152014

C. U.S. crude oil production

Quarterly

NOTE: The data are quarterly averages of monthly data. The data

extend

through 2018:Q2. Data from 2018:Q3 through 2019:Q4 are projections.

S

OURCE

: Department of Energy via Haver Analytics.

18 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

Real gross domestic product growth

slowed in the rst quarter, but spending

by households appears to have picked up

in recent months

After having expanded at an annual rate of

3percent in the second half of 2017, real gross

domestic product (GDP) is now reported to

have increased 2percent in the rst quarter of

this year (gure13). The step-down in growth

during the rst quarter was largely attributable

to a sharp slowing in the growth of consumer

spending that appears transitory, and gains in

GDP appear to have rebounded in the second

quarter. Meanwhile, business investment has

remained strong, and net exports had little

eect on output growth in the rst quarter. On

balance, over the rst half of this year, overall

economic activity appears to have expanded at

a solid pace.

The economic expansion continues to be

supported by favorable consumer and business

sentiment, past increases in household

wealth, solid economic growth abroad, and

accommodative domestic nancial conditions,

including moderate borrowing costs and easy

access to credit for many households and

businesses.

Gains in income and wealth continue to

support consumer spending . . .

Following exceptionally strong growth in the

fourth quarter of 2017, consumer spending

in the rst quarter of this year was tepid,

rising at an annual rate of 0.9percent. The

slowdown in growth was evident in outlays

for motor vehicles and in retail sales more

generally; moreover, unseasonably warm

weather depressed spending on energy services.

However, consumer spending picked up in

more recent months as retail sales rmed, and

PCE in April and May rose at an annual rate

of 2¼percent relative to the average over the

rst quarter (gure14).

Real disposable personal income (DPI), a

measure of after-tax income adjusted for

ination, has increased at a solid annual rate

of about 3percent so far this year. Real DPI

3

2

1

+

_

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

Percent, annual rate

2018201720162015201420132012

14. Change in real personal consumption expenditures

and disposable personal income

H1

NOTE

: The values for 2018:H1 are the annualized May/Q4 changes.

SOURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Personal consumption expenditures

Disposable personal income

2

4

6

8

10

12

PercentMonthly

2018201620142012201020082006

15. Personal saving rate

NOTE

: Data are through May 2018.

S

OURCE

:Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

1

2

3

4

5

Percent, annual rate

20182017201620152014201320122011

13. Change in real gross domestic product and gross

domestic income

Q1

SOURCE: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Gross domestic product

Gross domestic income

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 19

has been supported by the reduction in income

taxes owing to the implementation of the

Tax Cuts and Jobs Act (TCJA) as well as the

continued strength in the labor market. With

consumer spending rising just a little less than

the gains in disposable income so far this year,

the personal saving rate has edged up after

having fallen for the past two years (gure15).

Ongoing gains in household net worth likely

have also supported consumer spending.

House prices, which are of particular

importance for the balance sheet positions of

a large set of households, have been increasing

at an average annual pace of about 6percent in

recent years (gure16).

11

Although U.S. equity

prices have posted modest gains, on net, so far

this year, this attening followed several years

of sizable gains. Buoyed by the cumulative

increases in home and equity prices, aggregate

household net worth was 6.8times household

income in the rst quarter, down just slightly

from its ratio in the fourth quarter—the

highest-ever reading for that ratio, which dates

back to 1947 (gure17).

. . . and borrowing conditions for

consumers remain generally favorable . . .

Financing conditions for consumers are

generally favorable and remain supportive

of growth in household spending. However,

banks have continued to tighten standards

for credit cards and auto loans for borrowers

with low credit scores, possibly in response

to some upward moves in the delinquency

rates of those borrowers. Mortgage credit has

remained readily available for households with

solid credit proles. For borrowers with low

credit scores, mortgage nancing conditions

have eased somewhat further but remain tight

overall. In this environment, consumer credit

continued to increase in the rst few months

of 2018, though the rate of increase moderated

some from its robust pace in the previous year

(gure18).

11. For the majority of households, home equity

makes up the largest share of their wealth.

CoreLogic

price index

S&P/Case-Shiller

national index

20

15

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

Percent change from year earlier

201820162014201220102008

16. Prices of existing single-family houses

Monthly

Zillow index

N

OTE

: The data for the S&P/Case-Shiller index extend through April

2018.

The

data for the Zillow index and the CoreLogic index extend through

May

2018.

S

OURCE: CoreLogic Home Price Index; Zillow; S&P/Case-Shiller

U.S.

National Home Price Index. The S&P/Case-Shiller Index is a product of S&P

Dow

Jones Indices LLC and/or its affiliates. (For Dow Jones

Indices

licensing information, see the note on the Contents page.)

5.0

5.5

6.0

6.5

7.0

Ratio

2018201520122009200620032000

17. Wealth-to-income ratio

Quarterly

NOTE

: The series is the ratio of household net worth to disposable personal

income.

SOURCE: For net worth, Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release

Z.1,

“Financial

Accounts of the United States”; for income, Bureau of

Economic

Analysis via Haver Analytics.

600

400

200

+

_

0

200

400

600

800

1,000

Billions of dollars, annual rate

201820162014201220102008

18. Changes in household debt

Sum

Q1

NOTE

: Changes are calculated from year-end to year-end except

2018

changes, which are calculated from 2017:Q4 to 2018:Q1.

S

OURCE: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release Z.1,

“Financial

Accounts of the United States.”

Mortgages

Consumer credit

20 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS

40

20

+

_

0

20

40

60

80

Billions of dollars, monthly rate

201820162014201220102008

21. Selected components of net debt financing for

nonfinancial businesses

Sum

Q1

S

OURCE

: Federal Reserve Board, Statistical Release Z.1,

“Financial

Accounts of the United States.”

Commercial paper

Bonds

Bank loans

10

5

+

_

0

5

10

15

20

Percent, annual rate

201820172016201520142013201220112010

20. Change in real private nonresidential fixed investment

Q1

S

OURCE

: Bureau of Economic Analysis via Haver Analytics.

Structures

Equipment and intangible capital

. . . while consumer condence remains

strong

Consumers have remained upbeat. So far this

year, the Michigan survey index of consumer

sentiment has been near its highest level

since 2000, likely reecting rising income, job

gains, and low ination (gure19). Indeed,

households’ expectations for real income

changes over the next year or two now stand

above levels preceding the previous recession.

Business investment has continued

to rebound . . .

Investment spending by businesses has

continued to increase so far this year, with

notable gains for spending, both on equipment

and intangibles and on nonresidential

structures (gure20). Within structures,

the rise in oil prices propelled another steep

ramp-up in investment in drilling and mining

structures—albeit not yet back to the levels

recorded from 2012 to 2014—while investment

in nonresidential structures outside of the

energy sector picked up after declining in

2017. Forward-looking indicators of business

investment spending remain favorable on

balance. Business sentiment and the prot

expectations of industry analysts have been

positive overall, while new orders of capital

goods have advanced on net this year.

. . . while corporate nancing conditions

have remained accommodative

Aggregate ows of credit to large nonnancial

rms remained strong in the rst quarter,

supported in part by relatively low interest

rates and accommodative nancing conditions

(gure21). The gross issuance of corporate

bonds stayed robust during the rst half of

2018, while yields on both investment- and

speculative-grade corporate bonds moved

up notably but remained low by historical

standards (gure22). Despite strong growth in

business investment, outstanding commercial

and industrial (C&I) loans on banks’ books

rose only modestly in the rst quarter,

although their pace of expansion in more

recent months has strengthened on average. In

Consumer sentiment

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

Index

50

60

70

80

90

2018201620142012201020082006

Diffusion index

19. Indexes of consumer sentiment and income expectations

Real income expectations

N

OTE

: The consumer sentiment data are monthly and are indexed to 100 in

1966. The real income expectations data are calculated as the net percentage

of survey respondents expecting family income to go up more than prices

during the next year or two plus 100 and are shown as a three-month moving

average.

S

OURCE

: University of Michigan Surveys of Consumers.

MONETARY POLICY REPORT: JULY 2018 21

April, respondents to the Senior Loan Ocer

Opinion Survey on Bank Lending Practices,

or SLOOS, reported that demand for C&I

loans weakened in the rst quarter even as

lending standards and terms on such loans

eased.

12

Respondents attributed this decline in

demand in part to rms drawing on internally

generated funds or using alternative sources of

nancing. Meanwhile, growth in commercial

real estate loans has moderated some but

remains strong. In addition, nancing

conditions for small businesses appear to

have remained generally accommodative, with

lending standards little changed at most banks

and with most rms reporting that they are

able to obtain credit. Although small business

credit growth has been subdued, survey data

suggest this sluggishness is largely due to

continued weak demand for credit by small

businesses.

But activity in the housing sector has

leveled off

Residential investment, which rose a modest

2½percent in 2017, appears to have largely

moved sideways over the rst ve months of

the year. The slowing in residential investment

likely is partly a result of higher mortgage

interest rates. Although these rates are still

low by historical standards, they have moved

up and are near their highest levels in seven

years (gure23). In addition, higher lumber

prices and tight supplies of skilled labor

and developed lots reportedly have been

restraining home construction. While starts

of both single-family and multifamily housing

units rose in the fourth quarter, single-family

starts have been little changed, on net, since

then, whereas multifamily starts continued

to climb earlier this year before attening

out (gure24). Meanwhile, over the rst ve

months of this year, new home sales have

held at around the rate of late last year, but

sales of existing homes have eased somewhat

(gure25). Despite the continued increases

in house prices, the pace of construction has

12. The SLOOS is available on the Board’s website at

https://www.federalreserve.gov/data/sloos/sloos.htm.

Double-A

High-yield

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

Percentage points

2000 2003 2006 2009 2012 2015 2018

22. Corporate bond yields, by securities rating

Daily

Triple-B

N

OTE: The yields shown are yields on 10-year bonds.

S

OURCE

: ICE Bank of America Merrill Lynch Indices, used

with

permission.

Mortgage rates

85

105

125

145

165

185

205

Index

3

4

5

6

7

20182016201420122010

23. Mortgage rates and housing affordability

Percent

Housing affordability index

N

OTE: The housing affordability index data are monthly

through

April

2018, and the mortgage rate data are weekly through July 5, 2018.

At

an index value of 100, a median-income family has exactly enough income to

qualify

for a median-priced home mortgage. Housing affordability

is

seasonally adjusted by Board staff.

SOURCE

: For housing affordability index, National Association of

Realtors;

for mortgage rates, Freddie Mac Primary Mortgage Market Survey.

Multifamily starts

Single-family permits

0

.4

.8

1.2

1.6

2.0

Millions of units, annual rate

2018201620142012201020082006

24. Private housing starts and permits

Monthly

Single-family starts

N

OTE

: The data extend through May 2018.

SOURCE

: U.S. Census Bureau via Haver Analytics.

22 PART 1: RECENT ECONOMIC AND FINANCIAL DEVELOPMENTS