! ! !

Prepared by:

Mark Willingham, MS

Sophie Gralapp, MA

John P. Barile, PhD

Department of Psychology

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

2530 Dole Street, Sakamaki Hall C404

Honolulu, Hawaiʻi 96822

Law Enforcement Assisted

Diversion Honolulu

2-Year Program Evaluation Report

October 1, 2020

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

i!

This report presents the status of the Hawaiʻi Health and Harm

Reduction Center (HHHRC) Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion

Honolulu (LEAD HNL) program on the island of O‘ahu for the State

of Hawaiʻi, including the neighbor islands of Kaua’i, Maui, and the

Island of Hawaiʻi. This report includes background information on

the program, the evaluation approach, program implementation, and

presents outcomes and impacts for years 1 (July 1, 2018-July 31,

2019) and 2 (August 1, 2019-July 31, 2020) project period beginning

July 1, 2018 to July 31, 2020. It concludes with recommendations

based on these findings.

This report was prepared by the University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa LEAD Program Evaluation

Team with important contributions from the LEAD Honolulu Hui, as well as State of Hawaiʻi

neighbor island LEAD partners and staff.

Author Contact for questions regarding this report:

John P. Barile, PhD

Interim Director, Social Science Research Institute

Associate Professor of Psychology

College of Social Sciences

University of Hawaiʻi at Mānoa

2530 Dole Street

Saunders 704D

Honolulu, HI 96822-2294

Phone: (808) 956-7469

Email: [email protected]

Website: jackbarile.com | uhecolab.com

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

ii!

Table of Contents

I. Executive Summary …………………………………………………………….

1

II. LEAD Program Background……………………………………………...........

5

III. LEAD on the Neighbor Islands…….…………………………………………..

8

Expansion of LEAD…………………………………………...…..

9

Kaua’i…………………………………………………………………….…..

10

Maui……………………………………………………………………..…....

11

Island of Hawai’i……………………………………………………….….…

13

LEAD on the Neighbor Islands Summary…………………………….……...

15

IV. LEAD Honolulu Program Implementation…………………………………...

16

Triaged Only………………………………………………………….……...

17

Referrals…………………………………………………………..…………..

20

Enrollments………………………………………………………..…….…....

22

Service Engagement….………………………………….………..………….

28

Services Needed & Used……………...…………….….………….................

28

HHHRC Clinic Collaboration and LEAD Clients………...……….................

32

V. LEAD Honolulu Outcomes & Impacts………………………………………...

33

Short-Term Goals………………………………………………………...…..

35

Housing Stability…………………………………………………..…......

35

Substance Use….………………………………….…………….………..

37

Stress………………………….….………….............................................

39

Long-Term Goals……………………………………………………….…...

40

Emergency & Hospital Use………………………………….…………...

40

Crime & Recidivism….……………………………….…………….…….

41

Quality of Life………………………….….…………...............................

45

Client Testimonials……………………………………………….…............

48

Conclusions……………………………………………………….….............

50

VI. Recommendations……………………………………………………………….

51

Recommendations for the Program………………………………………….

52

Recommendations for Funders & Other Stakeholders……………...……….

53

VII. Next Steps………………………………………………………….….…………

54

For Evaluators………………………………………………………..……...

55

VIII. Appendices………………………………………….…………………………...

56

Appendix A: Logic Model…………………………………...……..………...

57

Appendix B: Evaluation Methodology..……………….….…………….........

58

Appendix C: Evaluation Timeline………………………………......………..

62

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

iii!

List of Figures

Fig. 1 Triage Age…………..………………………………………………………...….

19

Fig. 2 Triage Gender……………….………………………………...…………...........

19

Fig.!3!!Triage!Ethnicity…….…………………………..………………………..…………………………..

19

Fig. 4 Mode of Referrals for LEAD HNL Participants……..………………………..

21

Fig. 5 Referral Locations……………………………..………………………………...

22

Fig. 6 Enrolled Client Age……………………………...…….……......…………...…..

24

Fig. 7 Enrolled Client Gender……………….……………………………...…….……

24

Fig. 8 Enrolled Client Highest Level of Education.……………………………..…....

24

Fig. 9 Enrolled Client Family Status...…….…………………………………….….…

24

Fig. 10 Enrolled Client Ethnicity………………….....………………………….……...

25

Fig. 11 Enrolled Client Drug Use in the Past 6 Months.……………………………...

26

Fig. 12 Triage Drug Use in the Past 6 Months.……..………………………….……...

26

Fig. 13 Enrolled Client Experienced Homelessness in the Past 3 Years .......………..

27

Fig. 14 Triage Currently Experiencing Homelessness……………………...………...

27

Fig. 15 Triage & Referred Individuals Services Interested in Receiving…………….

29

Fig. 16 Triage & Referred Individuals Services Currently Receiving……………….

29

Fig. 17 Percent of Enrolled LEAD Clients Indicating Services Needed over Time in the

Program……………………………………………………………………….

30

Fig. 18 Percent of Clients Indicating Using Services over Time in the Program……...

31

Fig. 19 HHHRC Clinic Collaboration and Services Provided to Clients…….…..…….

32

Fig. 20 LEAD Theory of Change………………………………………………..…….

34

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

iv!

Fig. 21 Average Number of Days Used Each Substance in the Past Month at First &

Last Assessment Since the Start of the Program…………….…..……………

37

Fig. 22 Percent Change in Substance Use from First to Last Assessment…………...

38

Fig. 23 Change in Client Perceived Stress from First to Last Assessment in the Past

Month………………………………………………………………...……..

39

Fig. 24 Change in Client Usage of Emergency Rooms & Hospitals in the Past Month

from First to Last Assessment…....…………………………….………...

40

Fig. 25 Number of Citations Issued to LEAD Clients Prior to Referral Beginning July

1, 2015 – Most Frequently Issued……………………….………………..

42

Fig. 26 Number of Citations Issued to Triage Clients Prior to July 1, 2018, Beginning

July 1, 2015 – Most Frequently Issued……………………………….……

42

Fig. 27 LEAD Client Cited Encounter Frequency Per Client over the Course of the

Program……………………………………………………….......................

43

Fig. 28 Triaged only Clients Cited Encounter Frequency Per Client over the Course of

the Program….……………………………………………………………...

44

Fig. 29 Change in Community Support from First to Last Assessment……..………

45

Fig. 30 Change in Social Support from First to Last Assessment……………………

45

Fig. 31 Change in Client Health and Wellbeing from First to Last Assessment…….

46

Fig. 32 Frequency of Experiences with Trauma………………………………………

47

Fig. 33 LEAD Clients Compared to General HI Population in Number of Unhealthy

Days………………………………………………………………………….

47

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

1!

I. LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Program Evaluation Report

Executive Summary

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

2!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Program Evaluation Report

Executive Summary

Program Background

• The goal of LEAD HNL is to reduce client recidivism for minor offenses by diverting

individuals who have committed minor offenses away from the criminal justice system

and into the social services sector. The program seeks to achieve this by engaging clients

in social services aimed at addressing housing, substance use, behavioral health, and

physical health issues.

• As of September 2020, LEAD HNL diversion referrals have not begun. Therefore, all

referrals described in this report came through “social contact.” Social contact referrals

have been conducted in collaboration with Honolulu Police Department (HPD) Health

Efficiency Long-term Partnership (H.E.L.P.) initiative and the Sheriff’s Division of the

Hawai’i Department of Public Safety in collaboration with the Office of the Governor's

Coordinator on Homelessness.

• Between July 1, 2018 and July 31, 2020, 101 individuals who were referred to LEAD

through different outlets were provided services or triaged out to services through the

LEAD HNL program. Of those 101 individuals, 57 individuals were referred to LEAD

HNL through social contact referral and 44 were triaged out to other service providers.

Of those 57 referred clients, 50 were enrolled in and received services through LEAD

HNL.

Client Background

• Enrolled clients’ gender were comprised of 48% identifying as female, 40% identifying

as male, and 12% identifying as transgender or gender fluid 12%.

• Half of enrolled clients were Native Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (50%) and over half of

enrolled clients were multiracial (54%).

• Half of enrolled clients were single (50%) and nearly a quarter (22%) were divorced.

• The highest reported education achieved by clients was graduated from high school or

received a GED (36%). However, few enrolled clients graduated from college (4%).

• The majority of enrolled clients reported they were currently experiencing homelessness

(76%), and nearly a quarter (22%) had experienced homelessness within the past three

years but were not experiencing homelessness at the time of enrollment.

• At the time of enrollment, 78% reported using methamphetamine, 36% reported using

alcohol, and 36% reported using opioids and/or heroin within the six months prior.!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

3!

Findings

• Over the two-year study period, the vast majority of clients consistently cited permanent

housing as a service they needed.

• LEAD HNL client service use generally increased over time, particularly the use of case

management, medical services, transportation assistance, and permanent housing

services.

• On average, clients had 7% more cited encounters with law enforcement after referral to

the LEAD HNL program. But, this was substantially lower than the number increase in

citations of clients who were triaged into services, but not enrolled into the LEAD

program due to various reasons ranging from the program being at capacity to the

individual not fitting the program criteria (93%). This suggests that the number of

citations by HPD to people experiencing homelessness likely increased at a similar or

greater rate during this period.

• On average, LEAD HNL clients reported a decrease in use of emergency shelters (53%

decrease) and an increase in use of transitional shelters (46% increase).

• Despite increases in clients who lived in an independent apartment for the entire previous

month at first assessment (4%) to 33% at the last assessment, clients were still unlikely to

be living in a shared apartment (on average 3.21 days per month) or an independent

apartment (10.29 days a month) at last assessment.

• Eighteen out of the 49 LEAD HNL clients (37%) are currently housed with a housing

voucher.

a

• LEAD HNL clients indicated using methamphetamines 18.33 days in the previous month

when first assessed. Opioids/heroin was the second most frequently used substance at

11.67 days, followed closely by marijuana (11.56 days) and alcohol (6.3 days). No other

drugs surpassed an average of 6 days a month at first assessment.

• The average number of days a month LEAD HNL clients (who self-reported use) used

methamphetamines decreased by 23% (from and average of 18.33 days a month to 14.06

days a month, with 17% reporting no use at last assessment), while alcohol use increased

by 11% (an increase from just over 6 days a month to 7 days a month).

!

• Reports of client hospital admissions decreased from 10% of clients reporting being

admitted to a hospital during the previous month at first assessment to 7% at last

assessment. A small decrease in hospital admissions is not unexpected given that many of

the clients suffered from untreated medical conditions prior to obtaining services.

a

!Due to 1 LEAD client passing away, counts may reflect 49 clients versus 50 to show comparison. !

!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

4!

• Emergency room visits decreased from 32% of clients reporting visiting them in the

previous month to 14% at last assessment.

• While number of days in pain decreased slightly (2.88%), the number of physically

unhealthy days increased by 20% by July 2020. Conversely, last assessment before the

COVID-19 emergency orders indicated a 24% decrease in the number of days in

pain and the number of physically unhealthy days increased by 5% from first to last

assessment in the prior 30 days, indicating clients reported notably better physical

health before the COVID-19 emergency order date.

b

• It should be noted that despite some improvements in clients’ general health and quality

of life, they continue to fare much worse than the average adult living in Hawai’i.

Conclusions

• While the number of cited encounters with law enforcement for enrolled LEAD clients

slightly increased after referral to the program, the increase was substantially lower than

the number of cited encounters with law enforcement after the start of the LEAD program

for those who were triaged for the program but not enrolled, suggesting that the number

of citations by HPD to people experiencing homelessness may increase at a similar or

greater rate during this period, affecting the primary goal of reducing recidivism rates of

program clients. At the time of this report, changes in cited encounters was accomplished

solely through social referral, which lacks the potential threat of legal action if clients do

not engage with the program following referral.

• Our evaluation found notable improvements in the stability of housing experienced by

clients since enrollment in the program as well as their overall quality of life.

Specifically, participants increased the amount of social support they received, reported

decreased stress, and improved mental health. They still reported considerable substance

use; however, there were decreases in self-reported drug use for 6 out of 7 types of

substances used in the past month. Furthermore, operating under a harm reduction model,

these are the considerations that might be best addressed after a period of stabilization in

other aspects of clients’ lives.

• We recommend the continued expansion of the program across the entirety of the City,

County, and State, including continuing the LEAD neighbor island pilot programs that

lost funding for various reasons over the 2020 summer. We also strongly recommend the

introduction of the diversion arm of the program by establishing partnerships with local

law enforcement, the prosecutor’s office, and other criminal justice agencies. With the

potential costs savings associated with reduced hospital admissions and emergency room

use and the decreased burden on the criminal justice system, this program will likely

result in net savings as well as improving the lives of those to participate.!

b

!Outcomes and impacts related to the COVID-19 pandemic will be highlighted throughout the report.

These highlighted points are indicated by being in light blue and bold type face.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

5!

II. LEAD Program Background

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

6!

The LEAD Model

Law Enforcement Assisted Diversion (LEAD) is a diversion program that aims to improve

public safety and to reduce criminal behavior.

1

Under the LEAD program model, law

enforcement officers connect low-level, non-violent offenders or individuals at high risk of arrest

with social service providers in lieu of arrest. The LEAD program is unique from other diversion

programs in that:

• diversion occurs pre-booking instead of after arrest;

• LEAD provides participants with immediate case management;

• LEAD is a collaborative effort, involving law enforcement, community organizations,

and public officials

1

; and

• LEAD was funded and supported by the Hawaiʻi State Department of Health, Alcohol

and Drug Abuse Division (ADAD), which is also an active LEAD Hui participant.

The original LEAD program in Seattle, Washington showed successful outcomes. After three

years of operation, a 2015 study found that LEAD participants were 58% less likely to be

arrested after enrollment in the program compared to a control group that went through “system

as usual” criminal justice processing.

2

Additionally, preliminary program data collected by case

managers indicated that LEAD improved the health and wellbeing of people struggling with

poverty, drug use, and mental health problems. Furthermore, the collaboration between

stakeholders, who were often otherwise at odds with one another, proved an invaluable process-

oriented outcome.

3

LEAD Honolulu

In collaboration with Hawai’i Department of Health and the

Office of the Governor's Coordinator on Homelessness, the

Hawai’i state legislature funded the current program through

the Alcohol and Drug Abuse Division (ADAD) in 2017. The

“LEAD HNL” pilot launched July 1, 2018 and aimed to

follow the original LEAD model by focusing specifically on

people whose criminal activity is due to behavioral health

issues (the 2019 LEAD HNL 1-Year Program Evaluation

Report can be found at: https://www.hhhrc.org/lead).

4

LEAD HNL’s intensive case management further aims to

help individuals, many of whom have cycled in and out of

jails and prisons, receive the assistance they need to face

complex issues (e.g., homelessness, substance use, and

mental illness).

4

In addition to aiming to improve individual wellbeing,

LEAD HNL aims to help Hawai’i decrease recidivism

rates, address overcrowded correctional facilities, and

LEAD Hui: A major

component of LEAD HNL is the

engagement and coordination of

services with key stakeholders.

The “LEAD Hui” is a group of

over 30 organizations who meet

one time per month to

coordinate the implementation

of LEAD. Members include

homeless service providers,

substance use treatment

facilities, and representatives

from the Department of Health,

the Honolulu Police Department

(HPD), the Office of the

Governor's Coordinator on

Homelessness, and the Alcohol

and Drug Abuse Division

(ADAD).

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

7!

transform Hawai’i’s criminal justice system from punitive to rehabilitative. Given that nearly

three fourths of Hawai’i’s jail and prison population are incarcerated for misdemeanors, petty

misdemeanors, technical offenses, or violations

5

—the kinds of offenses targeted by LEAD—the

program is well-positioned to help address these systemic issues.

LEAD Evaluation Goals

This evaluation report will focus on the implementation of the LEAD program for the City and

county of Honolulu between July 1, 2018 and July 1, 2020 (Years 1 and 2), briefly introduce

LEAD pilot programs for the neighboring islands of Kaua’i, Maui, and the Island of Hawai’i,

(Year 1), and outline the evaluation methods used. In particular, this evaluation aims to:

• highlight key demographics of the LEAD clients;

• understand clients’ services needed and received while engaged with LEAD;

• changes in client progress between Years 1 and 2;

• assess fidelity to the LEAD model and any necessary modifications;

• detect and report outcomes and impacts (COVID-19 related where essential)

c

; and

• examine achievements and goals of LEAD HNL.

This report outlines progress achieved thus far and explains the evaluation plan and

implementation in more detail.

c

!Honolulu Mayor Kirk Caldwell issued a stay-at-home, work-from-home order for Honolulu that went

into effect on March 23, 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic. This order was originally meant to

be in effect until April 30, 2020; however, because of increased cases and community spread, the stay-

at-home, work-from-home order along with the March 26, 2020 Governor David Ige self-quarantine

14-day order were both continuously pushed back. These orders caused disruption of daily life for all of

the Hawai’i islands. LEAD staff felt the effects of the pandemic and political orders and case

management had to be restructured.!!

!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

8!

III. LEAD on the Neighbor Islands

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

9!

Expansion of LEAD

At the conclusion of Year 1 of LEAD HNL on Oʻahu, LEAD

expanded to the neighbor islands of Kaua’i, Maui, and the Island of

Hawaiʻi through funding provided by Act 209, Session Laws of

Hawaii 2018. Based on lessons learned from LEAD HNL, the Kaua’i,

Maui, and Island of Hawaiʻi pilots included a shelter and housing

component to provide short-term stabilization beds for LEAD clients.

The following organizations administered LEAD in partnership with

County Prosecuting Attorney’s offices and Police Departments:

• Kaua’i: Women in Need

d

• Maui: Mental Health Kokua

e

• Island of Hawaiʻi: Big Island Substance Abuse Council

f

Each individual LEAD pilot program is implemented differently than LEAD HNL in order to

allow for neighbor islands to make changes within each jurisdiction as deemed necessary to

maximize implementation in combination with adhering to the overall LEAD model and its key

principles as much as possible. Local adaptation of the overall LEAD model is integral to the

success of the program in that it helps to: gain buy-in from local partners and stakeholders and

give each individual program the flexibility to adjust to the needs of each individual community.

d

https://www.winhi.org

e

https://mhkhawaii.weebly.com

f

http://www.bisac.org !

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

10!

Kaua’i

According to local news, LEAD on the island of Kaua’i (LEAD Kaua’i) launched in December

of 2019 in Lihue, Kaua’i.

g

LEAD Kaua’i has screened 11 potential LEAD clients, but only 2

have had subsequent contact as of April 14, 2020. So far, recruiting LEAD Kaua’i clients has

been a difficult process for the program. To begin, potential clients are screened using the LEAD

Kaua’i screening form to determine if they are eligible for the program. A few potential clients

have completed the initial screening intake forms. However, staff followed-up with these

potential clients to build rapport and establish trust, but were unable to locate the potential

clients. LEAD Kaua’i staff are currently utilizing social referrals and outreach through the public

defender’s office and the prosecutor’s office. In addition, staff are working with a local judge to

try to establish some form of a jail diversion in the future. The public defender’s office,

prosecutor’s office, and local judge are providing potential clients for three different charges,

including theft and possession of 3 grams or less of marijuana.

It is of note that the recent COVID-19 pandemic has slowed these referrals down. So far, the

biggest challenge the LEAD Kaua’i staff are facing is locating potential clients through follow-

ups, such as incorrect contact information, telephones being out of service, and clients not being

at the locations where they were referred or are known to frequent. The majority of the potential

clients screened were homeless, suffered from substance use, a few had traffic citations, and

some have been engaged in mental health services.

LEAD Kaua’i collaborators include the Kaua’i Police Department (KPD), the prosecutor’s

office, the Department of Land and National Resources (DLNR), Mental Health Kokua, the park

rangers, the Housing Agency, the Chief of KPD, and Captain Green of KPD who all refer

potential clients to LEAD Kaua’i. LEAD Kaua’i has a good relationship with the public

defender’s office, but is working on improving their relationship with KPD and getting their buy-

in in order to collaborate with them to refer potential clients. LEAD Kaua’i staff is working with

the child welfare office to expand social referrals. Clients referred through the prosecutor’s office

receive a citation, and then the police officer sends LEAD Kaua’i staff a notice that the person

fits the description of a LEAD Kaua’i client. LEAD Kaua’i staff then follow-up with the client to

complete an initial screening with them. In regards to reissuing citations initially received by

clients, this decision depends upon what services the client might qualify for and if they

complete the services as well as if they agree to attend and complete treatment. Depending upon

how successfully the client completes the services in the program, the citation may be dropped

and if not, the citation will not be dropped. However, this criterion has not been fully established

because LEAD Kaua’i has not had a client complete the program yet.

LEAD Kaua’i does not have established team meetings at this time, but are working on

implementing regular team meetings for check-ins, establishing the groundwork for the program,

creating a better relationship with KPD and other key stakeholders, as well as client tracking.

LEAD Kaua’i has established an initial goal of recruiting 15 clients to start due to the high

g

https://www.khon2.com/local-news/kauai-launches-lead-program-to-help-people-at-risk/

!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

11!

intensity of case management services and the time involved serving clients. LEAD Kaua’i staff

are continuing to maintain their focus on getting LEAD Kaua’i up and running.

Maui

LEAD on the island of Maui (LEAD Maui) launched on May 1, 2019. LEAD Maui operates

through key partnerships with other agencies and programs, which include: Maui Police

Department (MPD), Mental Health Kokua (MHK), Ka Hale A Ke Ola Homeless Shelter

(KHAKO), and Aloha House (substance use treatment). LEAD Maui enrolls clients by

coordinating outreach twice a week with the Maui Police Department. This process involves an

early morning ride-along with sergeants, other police officers and MHK’s Homeless Outreach

Worker to engage in warm handoff referrals. The LEAD Maui MHK Outreach Worker with their

police partner listens to the police radio for individuals who may fit their client descriptions

(often houseless individuals engaging in interactions with police officers) so that they are able to

respond instead during their police ride-along. The intended response for these individuals

involves locating the individual and building rapport during their initial encounter with the

police. The LEAD Maui MHK Outreach Worker begins the process of determining if the

individual may be an eligible candidate for the program and then begins the case manager and

service provider processes if the individual fits the client criteria. The main goal of these

outreach social referrals with the Maui Police Department is to make initial contact with the

potential client for services such as entrance into a shelter or other services instead of arrest. This

process is a coordinated response in which everyone involved with LEAD Maui comes together

to reach out and do what it takes to get individuals into the program.

Utilizing these outreach efforts with weekly Maui Police Department ride-alongs minimizes the

amount of time it would take to do a partnering agency or social contact warm handoff, allowing

the Outreach Worker to meet the individual during their police encounter rather than trying to

follow-up with them at a later time. During this encounter, the Outreach Worker is able to get to

know the individual and build trust, which is a difficult process with marginalized populations.

The Outreach Worker is able to screen the individual, determine their needs, and begin the case

management process through providing and referring services, as well as intensive case

management going forward.

The goals of LEAD Maui and these outreach efforts with the Maui Police Department are to

enroll individuals into the program and get them into LEAD Maui beds when the client needs

immediate housing through KHAKO and MHK or referral to Aloha House. Because these

encounters are initially when the individual has encounters with the police, timing is often

limited and dependent upon a number of factors so the client may not fill out their initial LINA

for a few days after the encounter. LEAD Maui staff will then follow-up with the client to

complete their LINA, as well as the intake into the LEAD Maui program involving their own

initial screening form, a Maui Mental Health Kokua form. This form is completed with the client

a week after the Outreach Worker gets to know the client to allow for rapport and trust to be

built, which allows for more and improved client engagement to determine the best services to fit

their needs.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

12!

Along with the ride-alongs, there are Maui judges referring potential clients into LEAD Maui

through a court mandate; however, the majority of clients are enrolled through outreach efforts.

These court mandates may replace probation as a punishment if the client is able to successfully

engage with the LEAD Maui program and utilize case management. This may involve LEAD

Maui Outreach Worker and MPD navigating the court process with the client, providing them

with services, and reporting their successes or challenges with completing services to their

probation officer, which may negatively affect their completion of the program and possibly

enhanced criminal justice reaction.

LEAD Maui estimates that they have made successful contact with more than 800 individuals

through program efforts since May of 2019. These contacts may just include providing

information about services or programs, providing masks, and other lower level service

providing. The majority of clients were trying to find services for improved living conditions and

transitional housing. LEAD Maui places an emphasis on client mental health, and harm

reduction, which may be supported through finding housing, taking the client out of their current

situations, and supporting them through different avenues and services to ensure they are set up

for success. Every individual has different needs and goals such as psychiatry, transportation to

probation appointments, bus passes, housing, and the need for mental health professionals. Once

the client’s LINA assessment is completed, LEAD Maui staff has a better idea of the needs and

goals the client has and wants to focus on going forward.

LEAD Maui places a focus on getting their clients stabilized and set-up for a better life. Other

areas of focus include getting the client document-ready, family reunification, and any substance

treatment that may benefit the client. LEAD Maui staff places an emphasis on face-to-face

check-ins with clients. The amount of time clients are enrolled in LEAD varies depending upon

their needs. LEAD Maui MHK and KHAKO staff members conduct an initial assessment with

the client, a follow-up sometime in the middle of their care, and a follow-up before they are

discharged. Some clients are followed for a few months and some may need as long as a year

with the program. The client is able to make the choice on how long they are enrolled in the

program since LEAD Maui is a volunteer program, unless mandated by a judge.

Sample Maui Police Department LEAD Program Activities Report for the

months of November 1, 2019 to March 31, 2020:

Our CORE Sergeant, in addition to daily contacts with the Outreach Worker and

LEAD participants, made 372 field contacts through outreach and documented 87

cases with 127 charges related to response to calls for service and officer requests.

…Client A- Housed Private after LEAD program and LEAD/CORE

will follow due to court. No police involvements during & following

the LEAD program.

…Client B- Housed in Permanente Supportive Housing (Mental Health

Program) and will be followed by LEAD/CORE due to court. No police

involvements during & following the LEAD program.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

13!

…Client C- Housed in Permanente Supportive Housing. No police

involvements during & following the LEAD program.

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, traditional client interactions and recruitment efforts had to be

adjusted. LEAD Maui staff still met clients face-to-face when appropriate and necessary.

However, staff were not transporting clients to court and other criminal justice meetings or

hearings. All LEAD Maui staff were required to wear masks when interacting with clients for

their as well as the clients’ safety and health. LEAD Maui ceased accepting new clients on June

6

th

, 2020. LEAD Maui consistently conducted weekly meetings with Maui Police Dept., Mental

Health Kokua, Ka Hale A Ke Ola Homeless and Aloha House. Meetings involved checking-in

on clients and their status, housing status, number of clients in LEAD Maui beds, and other

probation or drug court officers’ check-ins and information sharing when necessary for specific

clients.

LEAD Maui has found that the program finds success through partnerships with Maui Police

Dept., Mental Health Kokua, Ka Hale A Ke Ola Homeless and Aloha House and other programs

and organizations, as well as a supportive relationship with the chief of the Maui Police

Department. There are agencies, organizations, and individuals on Maui who share the vision of

LEAD Maui of providing services for clients and improving their living conditions, which

creates an environment for partnership and program success.

Island of Hawai’i

LEAD on the Island of Hawaiʻi (LEAD IOH) began looking for clients in January of 2020. As of

April, 23, 2020, LEAD IOH has commenced providing case management services to 5 clients.

For the majority of these clients, case managers are focusing on clients receiving temporary

shelter; however, since the program is young, clients have yet to receive a full range of

programs. LEAD IOH staff do not have a set structure as far as data collection and assessment

tools yet, but staff are filling out the screening and a long intake and needs assessment (LINA)

form for each client. LEAD IOH staff are using these assessments as instruments and making

them their own based on the unique needs of LEAD IOH; however, since there are also partner

organizations completing these assessment tools, it is unknown if all partner organizations are

completing the screening and LINA forms. The data collected so far is spread out between the

different LEAD IOH partners currently working to find and serve clients.

LEAD IOH is currently utilizing a collaborative approach for finding clients. This is achieved

through a community partnership and network, including Going Home

h

, Bridge House

i

, and

HOPE services

j

. These organizations work collaboratively with LEAD IOH, which includes

these providers alternating partnering with the local Hawaiʻi Police Department officers on

Thursdays at 4 a.m. (i.e., meeting with Hawaiʻi Police Department officers to determine who will

h

https://www.goinghomehawaii.org

i

http://www.bridgehousehawaii.org

j

https://hopeserviceshawaii.org

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

14!

accompany them) in Kona to join forces to locate potential LEAD IOH clients through social

contact referrals

k

. Partner organizations coordinate with LEAD IOH to schedule Hawaiʻi Police

Department accompaniment for the month.

In doing so, case managers accompany Hawaiʻi Police Department officers to hotspots where

LEAD IOH-type citations and law breaking is often found, and Hawaiʻi Police Department will

hand off any potential LEAD IOH clients that have just been cited to start the process of LEAD

IOH engaging with the potential clients, beginning the screening process, and conducting

assessments. Hawaiʻi Police Department assigns a case number to these individuals, which is

later presented to Prosecuting Attorney’s office. However, there is not a set criteria yet for if and

how Hawaiʻi Police Department will make decisions to reissue citations. To date, no citations

have been reissued to any LEAD IOH clients. LEAD IOH service providers have communicated

that the Chief of the Hawaiʻi Police Department is willing to utilize LEAD IOH in order to

reduce citations and arrests, but Hawaiʻi Police Department officers expressed feeling that

LEAD IOH is yet another task for them to complete and a burden. Therefore, it may take

additional time to obtain buy-in from the officers of the Hawaiʻi Police Department.

Buy-in from the officers of the Hawaiʻi Police Department is paramount because the foundation

of the LEAD IOH program workflow involves Hawaiʻi Police Department officers making initial

contact with potential LEAD IOH clients that they encounter who might fit the program

requirements and then handoff the potential clients to LEAD IOH CMs to screen and later

follow-up with and begin providing case management and services. CMs use a weekly tracking

report that includes the deliverables rendered (e.g., screening form, assessments, etc.). These

tracking reports currently serve as a data collection and client tracking tool; they are not a direct

reflection of Honolulu LEAD evaluation and data collection.

LEAD IOH partners conduct monthly team meetings on the first Tuesday of each month. Topics

regarding clients, placement of clients, and their cases are discussed amongst these partner

organizations This allows the Prosecuting Attorney’s office to stay updated with each client and

their progress through the programs. Key stakeholders are provided the opportunity at this time

to check-in on the program and ask questions. Although the LEAD IOH team has set no specific

target number of clients, decisions surrounding this will occur as the program progresses.

It should be noted that COVID-19 has exacerbated start-up challenges for LEAD IOH

community partners and stakeholders. Other program challenges include lack of communication;

information was not disseminated to the individuals who were providing the service (e.g.,

Hawaiʻi Police Department and other service providers). This lack of communication issue was

not on the part of LEAD IOH; it was an internal issue for Hawaiʻi Police Department and other

service providers. LEAD IOH staff was forced to cease operations because the Hawaiʻi Police

Department was focusing primarily on the safety of community and the Prosecuting Attorney’s

office was working remotely due to courts being closed.

k

Social contact referrals are made for individuals who are perceived as high risk of arrest for low-level,

non-violent criminal offenses in the future, but do not necessarily involve a police citation.

!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

15!

LEAD on the Neighbor Islands Summary

• LEAD Kaua’i, LEAD Maui, and LEAD IOH all completed a pilot year for each of their

respective programs.

• All three programs were successful in establishing partnerships with other programs,

services, and departments to provide case management to clients and perspective clients.

• Each program was unable to establish a timeline to truly capture client changes-over-

time; however, each island was able to create and establish police buy-in that is crucial

for the LEAD model.

• There is a need to focus on the sustainability of the LEAD program on the neighbor

islands.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

16!

IV. LEAD Honolulu Program Implementation

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

17!

The evaluation team monitored LEAD HNL program implementation as well as client and

community-level outcomes for the first two years of the program. This section focuses on

program implementation, the triage, referral, and enrollment processes as well as service

provision. Data sources included archival data, field notes from case management and other

LEAD-related meetings, staff and client interviews, and client surveys.

Out of 101 individuals encountered and assessed through LEAD HNL, 44 were triaged out to

other service providers and 57 were referred into LEAD HNL as clients.

“Triaged Only” refers to individuals who were referred to LEAD but for various reasons were

not enrolled into the LEAD program but still screened for potential enrollment. LEAD program

screening provided the opportunity to be placed into the program (referred) or directed to

services but no case management (triaged only).

Triaged Only

In some cases, LEAD HNL staff and/or community partners encounter individuals that they

“triage” or refer out to other service providers. If the LEAD HNL program does not have

capacity, or the individual does not meet the requirements for either diversion or social contact

referral, community “triaged only” may be appropriate for the individual within the guidelines

set by the LEAD HNL triage protocol. The requirements for either diversion or social contract

referral requires verification by law enforcement, judiciary, or a community provider that the

individual’s “chaotic substance use” has resulted in a history of negative interactions with the

legal system as well as proof of such verification (e.g., police reports, direct observation by law

enforcement, information provided to law enforcement by credible source). Highlighting triage

clients provides a comparison group to enrolled LEAD clients to better assess outcomes.

Triaged Only Protocol

If a potential LEAD HNL client is screened and found to be ineligible for diversion or social

contact referral into LEAD HNL case management services, and LEAD HNL has capacity to

provide basic triage services to an individual, LEAD HNL staff may provide services to address

urgent subsistence matters. Basic triage services include, but are not limited, to:

• transportation to shelter;

• application to SNAP/financial assistance;

101 program screened and assessed

57 referred 44 triaged only

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

18!

• referral to healthcare, application to health insurance;

• connection to wound care, or wound care clinic; and

• reconnection to established social service provider.

LEAD HNL staff provide LEAD HNL triage services at the initial contact, and LEAD HNL

triage services are limited to 30 days to maintain program fidelity. If the triaged individuals’

needs extend beyond this timeframe, an exception to eligibility criteria may be considered. If an

exception to the eligibility criteria is granted, the client will be enrolled into LEAD HNL via

social contact referral on the date they were initially referred.

Triage Referral Process

Any law enforcement, judiciary, or community provider may make a triage referral through the

LEAD Triage Referral Process. To make a triage referral, the law enforcement, judiciary, or

community provider will email the LEAD HNL Program Manager the following information on

the individual in need of services:

• requested triage service;

• client’s last known location; and

• client’s contact information (if applicable).

If the requested triage service cannot be addressed within 30 days, the law enforcement,

judiciary, or community provider requesting services will be referred to the social contact

referral process.

Triaged Only: Demographics

The following section presents client demographics for the 44 individuals that were only triaged

at the time of their encounter with LEAD HNL and not referred to the program due to capacity

limits or the individual does not meet the program requirements for either diversion or social

contact referral:

• The largest percentage of triaged individuals were between 50 and 59 years of age (41%;

n=18) (See Fig. 1) and were men (43%; n=24) (See Fig. 2). About half of triaged

individuals identified as multiracial (49%; n=21), and about half identified as Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI) (47%; n=20) (See Fig. 3).

• The most common self-reported drugs used over the past 6 months were

methamphetamine (49%; n=21), marijuana/hashish (40%; n=17), and alcohol (38%;

n=16) (See Fig. 12).

• The vast majority of triaged individuals (98%; n=43) were currently experiencing

homelessness (See Fig. 14).

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

19!

• The largest percentage of triaged individuals were in their fifties (41%), and triaged

individual age ranged from 18 to 68, with an average age of 43 years (See Fig. 1).

• The majority of triaged individuals were male (55%), with the minority of triaged

individuals being transgender (2%) and female (43%; See Fig. 2).!!

• Triaged individuals were able to select more than one ethnicity. About half of triaged

individuals identified as multiracial (49%) and about half identified as NHPI (47%), with

just over half identifying as Caucasian/White (53%) (See Fig. 3).

2%

2%

2%

5%

5%

5%

5%

5%

16%

16%

47%

49%

53%

Micronesian (n=1)

Puerto Rican (n=1)

Japanese (n=1)

Korean (n=2)

Portuguese (n=2)

Hispanic (n=2)

African American (n=2)

Samoan (n=2)

Chinese (n=7)

Filipino (n=7)

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n=20)

Multiracial (n=21)

Caucasian/White (n=23)

Fig. 3 Triage Ethnicity

7%

27%

11%

41%

14%

Fig. 1 Triage Age (N = 44)

18-29 years (n=3) 30-39 years (n=12)

40-49 years (n=5) 50-59 years (n=18)

60-69 years (n=6)

43%

55%

2%

Fig. 2 Triage Gender (N = 44)

Female (n=19)

Male (n=24)

Transgender (n=1)

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

20!

Referrals

LEAD HNL clients were identified through referrals from community partners. These referrals

included both diversion referrals and social contact referrals. Individuals who have committed

low-level, non-violent offenses were eligible through diversion referrals from different criminal

justice agencies. Individuals who were perceived to be high risk for arrest were eligible for

LEAD HNL through social contact referrals from different community partners and not a result

law enforcement diversion. The following clients are LEAD HNL clients and do not reflect those

triaged only clients who only received triage services but were not admitted into LEAD HNL.

Mode of Referral

Diversion referrals. Provided there is an active diversion arm within LEAD HNL, diversion

requests take precedent over social contact referral. In place of an arrest or citation, LEAD HNL-

trained law enforcement officers refer individuals directly and immediately to LEAD HNL staff.

Eligible offenses include, but are not limited to trespassing, littering, park closure violations,

sit/lie offenses, and open container violations. Individuals who have committed violent offenses

within the last 10 years (e.g., drug traffickers, promoters of prostitution, sex offenders, and those

exploiting minors) are ineligible for LEAD HNL. As of the date of this report, diversion referrals

have not begun due to LEAD HNL still being in the process of facilitating a partnership with

HPD and the Prosecutor’s Office. Therefore, all referrals described in this report came through

social contact, as described below.

Social contact referrals. LEAD HNL will also accept social contact referrals from law

enforcement, that is, individuals perceived by officers as at high risk of arrest in the future for

low level drug activity. Since diversion has not yet begun, the primary avenue for social contact

referrals in the LEAD HNL program has been in collaboration with HPD’s Health Efficiency

Long-term Partnership (H.E.L.P.) initiative and the Sheriff’s Division of the Hawaiʻi Department

of Public Safety in collaboration with the Office of the Governor's Coordinator on

Homelessness. H.E.L.P. is a collaboration of police officers, social service workers, and

advocates who jointly conduct outreach aimed at providing connections for individuals to shelter

and/or detox services.

Social contact criteria. All social contact referrals to LEAD HNL must meet the following pre-

requisites:

• Verification by law enforcement, judiciary, or community provider that the individual’s

“chaotic substance use” has resulted in a history of negative interactions with the legal

system.

o Chaotic substance use:

§ any diagnosed history of Substance Use Disorder (SUD) from the DSM-V

criteria; or

§ any use of narcotic, stimulant, alcohol, or other illicit substance in a public

area resulting in a public safety concern.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

21!

• Verification by law enforcement, judiciary, or community provider of chaotic substance

use:

o police reports, arrests, jail bookings, criminal charges, or convictions indicating

that the individual was engaged in chaotic substance use; or

o law enforcement has directly observed the individual's chaotic substance use; or

o law enforcement has a reliable basis of information to believe that the individual

is struggling with chaotic substance use, such as information provided by another

first responder, a professional, or credible community members.

Other social contact referral methods

include direct recommendations

from officers or Sheriff deputies. In

addition to accompanying HPD on

H.E.L.P Honolulu operations, LEAD

staff regularly accompany the

Sheriff’s Capitol Patrol unit on

patrols in the Iwilei area and to

Community Outreach Court (See

Fig. 4).

Since July 1, 2018, 57 individuals have been referred to LEAD HNL through “social contact

referral.”

• Of these 57 referrals, the majority (54%) were through the H.E.L.P program.

• Over a third (35%) were referred from the Sheriff’s Division.!

54%

35%

5%

2%

4%

Fig. 4 Mode of Referrals for LEAD HNL

Participants (N=57)

HELP HNL (n=31)

Sheriff's Division (n=20)

Community Outreach

Court (n=3)

Point-in-Time (n=1)

HHHRC Walk-in (n=2)

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

22!

Fig. 5 Referral Locations

The majority of referrals were from

the 96817 zip code area (68%,

n=39), which includes Iwilei (n=14),

Chinatown (n=11), Aʻala Park (n=8),

River Street (n=5), and Pauahi Street

(n=1) (See Fig. 5).

Of the eleven people who were

referred from zip code 96813, five

were referred from Kakaʻako Park,

three were referred from Community

Outreach Court, two were referred

from Iolani Palace, and one was

referred from HHHRC walk-in (See

Fig. 5).

Of the four people referred from 96814, two were referred from Thomas Square Park, one was

referred from Ala Moana, and one was referred from Makiki. Another 2 people were referred

from Kapiʻolani Park (96815) (See Fig. 5).

Furthermore, the area assocaited with the 96817 zip code provided the most LEAD referrals and

according to the 2020 Oahu Point in Time Count is the location with the largest number of

unsheltered individuals. Indicating LEAD HNL is serving the hardest hit area of homelessness.

l

Intake Procedures

Once the referred individual has accepted the referral, LEAD HNL staff arrive on-site to conduct

an initial intake and to schedule a follow-up appointment to complete a full needs assessment

and begin to link the client with services. These clients are not diversion referrals and enrollment

in to LEAD does not influence any law enforcement charges or offenses.

Enrollments

Out of 57 individuals referred to LEAD HNL, 50 are enrolled in LEAD HNL.

l

The reasons for 7

out of 57 individuals referred to LEAD HNL not being enrolled vary, with the most common

reason being that the individual did not follow up with LEAD HNL staff to complete a long

intake and needs assessment (LINA). Clients who have completed a LINA with a LEAD HNL

case manager are considered enrolled in the program. LEAD HNL case managers provided

intensive follow-ups, calls, client scheduling and meetings, and other intensive avenues to aid in

l

Social contact referrals are made for individuals who are perceived as high risk of arrest for low-level,

non-violent criminal offenses in the future, but do not necessarily involve a police citation.

l

!Due to 1 LEAD client passing away, counts may reflect 49 clients versus 50 to show comparison. !

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

23!

turning referrals into enrolled clients. Currently, completing the LINA is the only requirement

for participation in the LEAD HNL program.

Enrolled Client Demographics & Background

The following section presents client demographics for clients at the time of enrollment into

LEAD HNL:

• At the time of enrollment, the largest

percentage of the 50 enrolled clients

were between 50 and 59 years of age

(36%; n=18) (See Fig. 6). The

majority of clients are women (48%;

n=24) (See Fig. 7) and have

graduated high school or obtained

their GED (36%; n=18) (See Fig. 8).

Just over a quarter of clients have

completed 9

th

to 11

th

grade (28%;

n=14) or some college (28%; n=14)

(See Fig. 8). However, only a few

clients graduated from college (4%;

n=2) (See Fig. 8). Half of the

enrolled clients have never been

married (50%; n=25) and nearly a

quarter are divorced (22%; n=11)

(See Fig. 9).

• The largest percentage of triaged

individuals were between 50 and 59

years of age (41%; n=18) (See Fig.

1) and were men (43%; n=24) (See

Fig. 2). About half of triaged

individuals identified as multiracial

(49%; n=21), and about half

identified as Native Hawaiian/Pacific

Islander (NHPI) (47%; n=20) (See

Fig. 3).

• The majority of enrolled clients

identified as multiracial (54%;

n=27), and half identified as Native

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (NHPI)

(50%; n=25) (See Fig. 10).

• At the time of enrollment, 78%

reported using methamphetamine,

36% reported using alcohol, and

36% reported using opioids and/or

heroin within the six months prior

(See Fig. 11).

• The vast majority of enrolled clients

reported currently experiencing

homelessness (76%; n=38), and

nearly a quarter had experienced

homelessness within the past three

years but were not currently

experiencing homelessness (22%;

n=11) (See Fig. 13).

57 referred

7 referred but not enrolled 50 referred and enrolled

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

24!

• The majority of enrolled clients were aged fifty or older (60%) and client age ranged

from 21 to 71, with the average age of 49.1 years (See Fig. 6).

• The largest percentage of enrolled clients were female (48%), and 6 clients identified as

either transgender or gender fluid (12%) (See Fig. 7). !

• The majority of clients finished high

school or obtained their GED (36%), with

an equal amount reporting having

completed 9

th

to 11

th

grade only (28%) or

some college (28%). Only 2 clients

graduated from college (4%) (See Fig. 8).

!

2%

22%

4%

18%

50%

4%

Married (n=1)

Divorced (n=11)

Widowed (n=2)

Separated (n=9)

Never Married/Single (n=25)

Unmarried Couple (n=2)

Fig. 9 Enrolled Client Family Status (N=50)

10%

16%

14%

36%

22%

2%

Fig. 6 Enrolled Client Age (N =50)

18-29 years (n=5) 30-39 years (n=8)

40-49 years (n=7) 50-59 years (n=18)

60-69 years (n=11) 70-79 years (n=1)

48%

40%

12%

Fig. 7 Enrolled Client Gender (N =50)

Female (n=24)

Male (n=20)

Transgender or Gender Fluid (n=6)

28%

36%

28%

4%

2%

Fig. 8 Enrolled Client Highest Level

of Education (N =50)

8th grade or less (n=1)

9th - 11th Grade (n=14)

Graduated or GED (n=18)

Some College (n=14)

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

25!

• At the time of enrollment, half (50%) of enrolled clients had never been married. Eleven

clients (22%) are divorced, and 9 clients (18%) are separated from a partner (See Fig. 9).

• Enrolled clients were able to select more than one ethnicity. The majority of enrolled

clients identified as multiracial (54%), and half (50%) identified as NHPI (See Fig. 10).

Compared to the overall population on Oʻahu, NHPIs and

multiracial individuals are overrepresented in referred and

enrolled LEAD HNL clients. NHPI and multiracial

individuals made up 9.6% and 22.8% of Honolulu County’s

population and 10.1% and 24.2% of Hawaiʻi’s population

in 2019, respectively,

6

compared to 50% and 54% of LEAD

HNL referrals. However, the program’s referred and

enrolled client racial breakdown reflects recent data

showing that NHPIs and multiracial individuals are

disproportionately represented in the homelessness population on Oʻahu, comprising 31% and

25% of the homeless population.

7

Additionally, data shows that Native Hawaiians are over-represented in the prison population,

both as seen in the LEAD Year 1 report and other reports.

4,5

Thus, the enrolled clients’ racial

composition roughly reflects those most likely to experience homelessness and/or incarceration

on Oʻahu, as seen in both years of LEAD HNL program implementation.

2%

4%

2%

6%

6%

10%

10%

12%

14%

14%

14%

42%

50%

54%

Micronesian (n=1)

Samoan (n=2)

Korean (n=1)

Portuguese (n=3)

American Indian (n=3)

Puerto Rican (n=5)

Hispanic (n=5)

Japanese (n=6)

African American (n=7)

Chinese (n=7)

Filipino (n=7)

Caucasian/White (n=21)

Hawaiian/Pacific Islander (n=25)

Multiracial (n=27)

Fig. 10 Enrolled Client Ethnicity

According to the 2020

Point-in-Time Count,

NHPIs comprised the

largest percentage of the

homeless population (31%),

followed by multiracial

(25%).

7

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

26!

• The vast majority of enrolled clients self-reported using methamphetamine (78%) over

the past 6 months (See Fig. 11).

• Enrolled clients self-reported that the drugs most commonly utilized over the past 6

months (other than methamphetamine) were alcohol (36%), opiods/heroin (36%), and

marijuana (30%) (See Fig. 11).

• Triaged only individuals self-reported that the drugs most commonly utilized over the

past 6 months were methamphetamine (49%), marijuana/hashish (40%), and alcohol

(38%) (See Fig. 12).

• Triaged individuals self-reported that the drugs least commonly utilized over the past 6

months were cocaine (7%), benzodiazepines (5%), and opiods/heroin (5%).

• LEAD clients (78%) reported more methamphetamine use than triaged only clients

(49%) during the 6 months prior to their first assessment.

36%

10%

36%

10%

30%

78%

4%

Fig. 11 Enrolled Client Drug Use in

the Past 6 Months (N =50)

Alcohol (n=18) Benzodiazepines (n=5)

Opiods/heroin (n=18) Cocaine (n=5)

Marijuana (n=15) Methamphetamine (n=39)

Other (n=2)

38%

5%

5%

7%

40%

49%

Fig. 12 Triage Drug Use

in the Past 6 Months (N =44)

Alcohol (n=16) Benzodiazapines (n=2)

Opioids/Heroin (n=2) Cocaine (n=3)

Marijuana/Hashish (n=17) Methamphetamine (n=21)

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

27!

!

• At the time of enrollment, the majority of clients were currently experiencing

homelessness (76%) (See Fig. 13).

• Less than a quarter of clients had experienced homelessness within the past three years

(22%); however, were not homeless at the time of enrollment (See Fig. 13).

• At the time of triage, the vast majority of triaged only individuals (98%) were currently

experiencing homelessness, with only a small minority being housed (2%) (See Fig. 14).

Triage clients (98%) were more likely to be currently homeless than LEAD clients (76%) during

first assessment.

m

Due to 1 LEAD client passing away, counts may reflect 49 clients versus 50 to show comparison. !

22%

76%

2%

Fig. 13 Enrolled Client Experienced

Homelessness in the Past 3 Years

(N =50)

Yes (but not currently homeless) (n=11)

Yes (currently homeless) (n=38)

Missing (n=1)

98%

2%

Fig. 14 Triage Currently

Experiencing Homelessness (N =44)

Yes (n=43) No (n=1)

At the time of this report, 18 out of the 49 LEAD HNL clients (37%) were currently

housed through different agencies, as well as through a collaboration with Partners

in Care (PIC) Oahu’s Continuum of Care Coordinated Entry System (CES).

m

Four

were housed through the Institute for Human Services, 4 through Catholic Charities

Hawaii, 2 through Honolulu Community Action Project, and 1 each through

HHHRC, Section 8, Kalihi Palama Health Center, Villages of Maili: Bridge Housing

provided by CCH, Gregory House, and self-housed.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

28!

Service Engagement

After enrollment and completing the Long Intake and Needs Assessment (LINA), LEAD HNL

case managers provide intensive case management services to help connect clients to other

services. About 78% (n=39) of the 50 enrolled clients are actively engaging in LEAD case

management services. Of the 50 enrolled clients, 10 individuals are not actively working with

their case managers for reasons ranging from the client has received the services they require

from the program and do not need hands-on assistance at the moment, as well as the case

manager has not been able to locate the client for an extended period of time, but are still

considered LEAD clients, and 1 individual is deceased.

Services Needed & Used

The following section presents triaged only individuals and

LEAD HNL clients’ self-reported services interested in

receiving/needed and services currently receiving/used.

Triaged individuals self-reported the types of services they

would like to utilize (See Fig. 15) as well as the types of

services utilized within the past 30 days (See Fig. 16).

LEAD HNL clients’ self-reported the types of services they

would like to utilize (See Fig. 17) as well as services

utilized within the past 30 days (See Fig. 18) at the time of

referral, baseline, and at subsequent follow-up time periods.

57 referred

7 referred, but not

enrolled

50 referred and enrolled

10 enrolled, but not

engaged

39 enrolled and engaged

("active")

1 deceased

50'Clients'with'

LINAs'(Baseline)

42'Clients'with''

FLINAs'(Last'

Assessment)

Operational Work Group:

LEAD HNL utilizes weekly

meetings to discuss and

coordinate care with community

partners, such as representatives

from HPD, the Office of the

Governor's Coordinator on

Homelessness, and the funding

agency ADAD.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

29!

Fig. 15 Triage & Referred Individuals Services Interested

in Receiving

• Triaged individuals were less interested in receiving

services than referred individuals except for emergency

shelter/temporary housing – triaged individuals were more

interested (64%) than referred individuals (40%).

• The majority of triaged individuals were interested in

receiving permanent housing (66%), food/clothing (64%),

and emergency shelter/temporary housing (64%).!

!

• The majority of referred individuals were also interested in

receiving permanent housing (82%) and food/clothing

(73%). In addition, the majority indicated needing case

management (89%), ID assistance (73%). Transportation

assistance (62%), mental health services (60%), disability

services (including SSI & SSDI) (56%), and legal services

(55%).!

Fig. 16 Triage & Referred Individuals Services Currently

Receiving

• The majority of triaged and referred individuals were not

currently receiving services.

• The services most utilized by triaged individuals were

food/clothing (30%) and medical services (27%).

• The services most utilized by referred individuals were

medical services (47%) and disability services (including

SSI & SSDI) (20%).

• Generally speaking, both triaged and referred individuals

reported minimal or no use of services, suggesting this

population is in grave need of support.!

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

30!

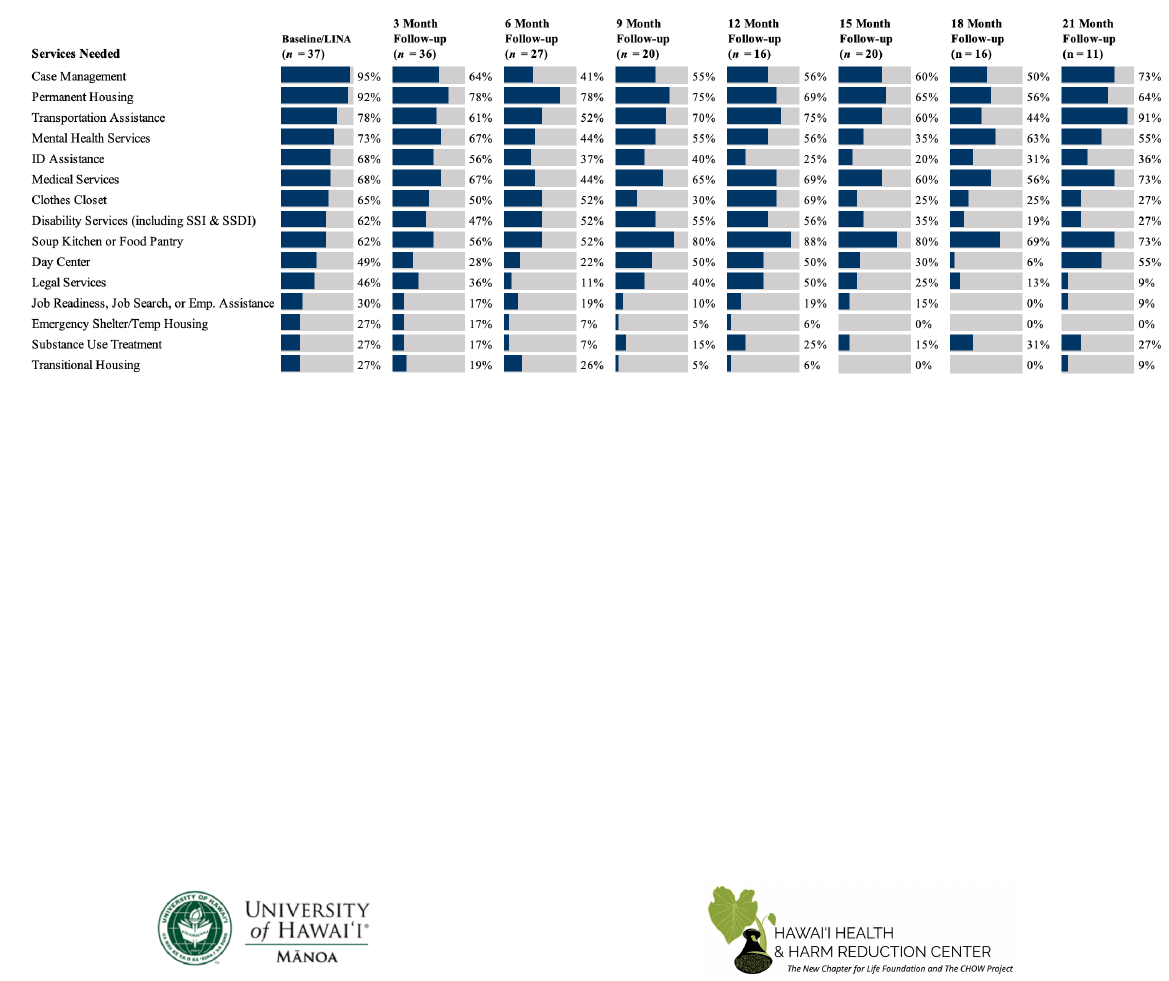

Fig. 17 Percent of Enrolled LEAD Clients Indicating Services Needed over Time in the Program

• At baseline, the majority of clients indicated needing 9 of the 15 services listed, with the vast majority indicating needing case

management services (95%) and permanent housing (92%).

• At baseline, about three quarters of clients indicated needing transportation assistance (78%) and mental health services (73%).!

• At baseline, over half of clients indicated needing ID assistance (68%), medical services (68%), clothes closet (65%), disability

services (including SSI & SSDI) (62%), and soup kitchen or food pantry (62%).

• The need for ID assistance dropped dramatically from 68% at baseline to 20% at 15-month follow-up.

• The need for clothes closet dropped dramatically from 65% at baseline to 25% at 15-month follow-up.

• At baseline and at all follow-up assessments, permanent housing continues to be a persistent need of the majority of clients.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

31!

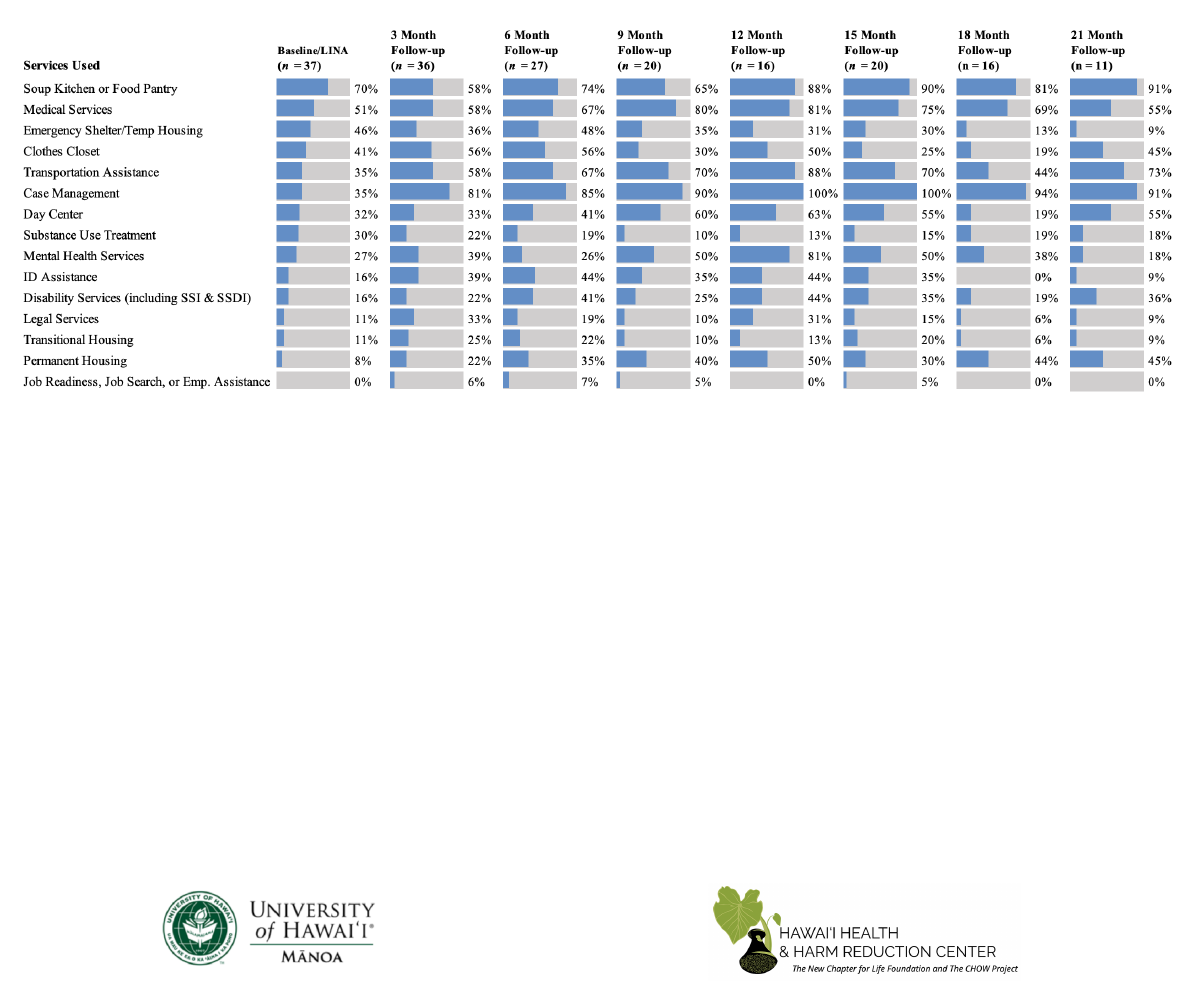

Fig. 18 Percent of Clients Indicating Using Services over Time in the Program

• At baseline, the majority of clients indicated using only two services – soup kitchen or food pantry (70%) and medical services

(51%). This is in stark contrast to findings that the majority of clients indicating needing nine services at baseline.

• Use of transportation assistance increased substantially from 35% at baseline to 67% at 24-month follow-up.

• Use of case management increased from 35% at baseline to 100% at 15-month follow-up as well as use of mental health

services, which increased from 27% at baseline to 50% at 15-month follow-up, which suggests that clients are receiving

services that were indicated by the majority of clients as services they needed at baseline.

• Use of permanent housing increased from 8% at baseline to 50% at 15-month follow-up, suggesting that LEAD is helping

clients obtain permanent housing, while also indicating the need for permanent housing remains a persistent need for clients.

• At baseline and all follow-up assessments, soup kitchen or food pantry and medical services continues to be utilized by the

majority of clients, suggesting that clients still need to utilize services for meeting basic needs, such as food and medical care

after being enrolled into the program.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

32!

HHHRC Clinic Collaboration and LEAD Clients

• HHHRC provides clinical services to LEAD clients and other program-based clients and

communities. Clinical services include rapid testing for Hepatitis C Virus (HCV), HIV

testing, wound care, and Buprenorphine for opioid treatment, housing voucher programs,

and other clinical services. Some services are handled and distributed within the HHHRC

clinic and others are connected and referred to outside services.

• At the time of this report, 18 clients are currently housed through a HHHRC collaboration

with Partners in Care (PIC) Oahu’s Continuum of Care Coordinated Entry System (CES)

partnerships (36%), 7 clients have received HCV tests (14%), and 4 clients have been

provided buprenorphine for opioid treatment (8%) (See Fig.19). Out of the 7 clients who

have received HCV tests, 3 clients had multiple HCV tests.

36%

16%

14%

12%

8%

Clients housed through HHHRC partner

agencies (n=18)

Clients provided HCV navigation (n=8)

Clients provided HCV tests (n=7)

Clients provided HCV treatment (n=6)

Clients provided Buprenorphine medication-

assisted treatment (MAT) (n=4)

Fig. 19 HHHRC Clinic Collaboration and Services Provided to Clients

(N=50)

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

33!

V. LEAD Honolulu Outcomes & Impacts

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

34!

In addition to examining program process, the evaluation team assessed program outcomes and

impacts based on goals identified in the LEAD Theory of Change (See Fig. 20). This section of the

report assesses program progress toward short-term and long-term goals for Years 1 and 2 (since

the start of the program) adhering to the harm reduction approach utilized by the LEAD program.

Fig. 20 LEAD Theory of Change

What is a “harm reduction approach?” The harm reduction approach seeks to reduce the adverse

consequences of drug use among persons who continue to use drugs. It developed in response to

the excesses of a “zero tolerance approach”. Harm reduction emphasizes practical rather than

idealized goals. It has been expanded from illicit drugs to legal drugs and is grounded in the

evolving public health and advocacy movements.

[Single, E. (1995). Defining harm reduction. Drug and Alcohol Review, 14(3), 287-290.]

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

35!

The following evaluation presents findings from Years 1 and 2 combined (i.e., clients’ first and last

assessment). It should be noted that findings presented in bold faced light blue indicate findings

for the first and last assessment of LEAD HNL clients from before the March 23, 2020

executive/emergency orders due to the COVID-19 pandemic to demonstrate any noticeable

differences in findings after the city-wide shutdown.

Short-Term Goals

Short-term goals include increased housing stability and decreased substance use and stress.

Housing Stability

The evaluation team assessed changes in housing by examining the number of days lived in

different locations for the last 30 days at baseline and follow-up. Of the 50 enrolled clients, 42

clients completed at least the baseline and a follow-up assessment. The time between baseline

and last assessment for these clients ranged 3-23 months, with an average of 13.5 months.

At baseline, the average number of days spent living on the street was 19.76 during the past 30

days. The average was 10.43 days during the past 30 days at the last assessment, showing a 47%

decrease since the start of the program.

!

# Days sleeping on

street/park/beach

47%

Additionally, the average number of days spent in an emergency shelter decreased from 3.12 to

1.55 days, while the average number of days in a transitional shelter increased from 1.37 to 2.00

days.

• Last assessment before the COVID-19 emergency orders indicated an average

increase by 188% from 1.37 days at first assessment to 3.94 days at last assessment for

the average number of days spent in a transitional shelter in the 30 days prior, which

is a larger increase than first (1.37) and last assessment (2.00) after COVID-19

indicating clients were using transitional shelters more before the COVID-19

pandemic.!

The percentage of clients who were housed for the

entire previous month increased from 13% at first

assessment to 48% at the last assessment.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

36!

# Days staying in emergency shelter

50%

# Days living in transitional housing

46%

These findings may reflect the change in the average number of days living in a shared or

independent apartment, which both increased from 1.47 and 1.63 days at first assessment to 3.21

and 10.29 days at last assessment, respectively. These changes may have contributed to the

reduction in emergency shelter use between assessments

# Days living in shared apartment

118%

# Days living in independent apartment

531%

The client average number of days in the past month sleeping on the streets was higher than other

sleeping locations at both first and last assessment; however, there was a 47% decrease from 19.76

days at first assessment to 10.43 days at last assessment.

• Last assessment before the COVID-19 emergency orders indicated an average

decrease by 61% for the average number of days spent sleeping on the streets from

19.76 days at first assessment to 7.69 days at last assessment.

The average number of days spent in independent apartment increased 531%, from 1.63 days at

first assessment to 10.29 days at last assessment.

These findings suggest that LEAD clients are spending less time on the streets

and more time in transitional housing or housed in an apartment since enrolling

in the program; however, there was a larger decrease in the number of days

sleeping on the streets and time in transitional housing before COVID-19.

The percentage of clients who lived in

an independent apartment for the

entire previous month increased from

4% at first assessment to 33% at the

last assessment.

LEAD Honolulu 2-Year Evaluation

! ! !

37!

What has changed in your life since starting LEAD?

“My court case recently got dropped and I’ll soon be off probation,

the (LEAD HNL) team helped me get there.”

– LEAD HNL Client

“I reunited with my family; I get to create memories with my

grandkids.”

– LEAD HNL Client

“I got sober and had a healthy baby girl. I also got married and

have my own place.”

– LEAD HNL Client

Substance Use

Using self-reported substance use data, evaluators assessed changes in LEAD HNL clients’

substance use and engagement in treatment services.

Figure 20 provides the average number of days clients used each substance in past month at first

and last assessment.

2.46

5.00

18.33

11.67

11.56

6.30

6.00

2.32

0.00

14.06

9.29

8.65

7.00

3.85

Cocaine Synthetic

marijuana/K2

Methamphetamine Opiods/heroin Marijuana/hasish Alcohol Benzodiazepines

Fig. 21 Average Number of Days Used Each Substance in Past Month at