Chinese Investments

in European

Maritime

Infrastructure

Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

Directorate-General for Internal Policies

PE 747.278 - September 2023

EN

STUDY

Requested by the TRAN Committee

Abstract

This study looks at Chinese investments in maritime

infrastructures through the lens of ‘de-risking’ for the first time. It

provides a comprehensive overview of Chinese investments in

the European maritime sector over the past two decades and

weighs the associated risks. The study borrows the framework

adopted by the National Risk Assessment of the Kingdom of the

Netherlands 2022 for its risk assessment and further develops it to

score the impact and likelihood of the investments across five

major threat areas: EU-level dependency risk, individual

dependency risk, coercion/influence risk, cyber/data risk and

hard security risk. The analysis illustrates that the risks remain

insufficiently understood by Member States, despite their high

likelihood and/or impact. This is particularly true for economic

coercion and cyber/data security risks.

RESEARCH FOR TRAN COMMITTEE

Chinese Investments

in European

Maritime

Infrastructure

This document was requested by the European Parliament's Committee on Transport and Tourism.

AUTHORS

Mercator Institute for Chinese Studies (MERICS): Francesca GHIRETTI, Jacob GUNTER, Gregor SEBASTIAN

The Vienna Institute for International Economic Studies (wiiw): Meryem GÖKTEN, Olga PINDYUK,

Zuzana ZAVARSKÁ

Institute of International Economic Relations: Plamen TONCHEV

Research administrator: Davide PERNICE

Project, publication and communication assistance: Mariana VÁCLAVOVÁ, Kinga OSTAŃSKA, Stephanie

DUPONT

Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, European Parliament

LINGUISTIC VERSIONS

Original: EN

ABOUT THE PUBLISHER

To contact the Policy Department or to subscribe to updates on our work for the TRAN Committee

please write to: Poldep-[email protected]opa.eu

Manuscript completed in September 2023

© European Union, 2023

This document is available on the internet in summary with option to download the full text at:

https://bit.ly/3rlVcff

This document is available on the internet at:

http://www.europarl.europa.eu/thinktank/en/document/IPOL_STU(2023)747278

Further information on research for TRAN by the Policy Department is available at:

https://research4committees.blog/tran/

Follow us on Twitter: @PolicyTRAN

Please use the following reference to cite this study:

Ghiretti, F, Gökten, M, Gunter, J, Pindyuk, O, Sebastian, G, Tonchev, P, Zavarská, Z, 2023, Research for

TRAN Committee – Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructure, European Parliament,

Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels

Please use the following reference for in-text citations:

Ghiretti et al (2023), Research for TRAN Committee – Chinese Investments in European Maritime

Infrastructure, European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies, Brussels

DISCLAIMER

The opinions expressed in this document are the sole responsibility of the authors and do not

necessarily represent the official position of the European Parliament.

Reproduction and translation for non-commercial purposes are authorized, provided the source is

acknowledged and the publisher is given prior notice and sent a copy.

© Cover image used under the licence from Adobe Stock

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

3

CONTENTS

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS 4

LIST OF FIGURES 7

LIST OF TABLES 7

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 8

1. INTRODUCTION 10

1.1. Scope of the study 10

1.2. Overview of China as a maritime power 11

1.3. Specificities of Chinese direct investments 12

1.4. Chinese investments in the maritime sector in Europe 12

2. CASE STUDIES AND RISK ASSESSMENTS 16

2.1. EU-level dependency risk assessment 17

2.2. Piraues, Greece 21

2.3. Hamburg, Germany 28

2.4. Kumport, Turkey 34

2.5. Impact on EU of Chinese investments in European Neighbourhood 38

2.6. Comparison of key regulations between the EU and US related to FDI

screening and maritime cabotage law 39

3. CONCLUSION AND POLICY RECOMMENDATIONS 41

REFERENCES 44

ANNEX 47

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

4

LIST OF ABBREVIATIONS

BMI

German Ministry of the Interior

BMWK

German Federal Ministry of Economic Affairs and Climate Action

BoD

Board of directors

BRI

Belt and Road Initiative

BSI

German Federal Office for Information Security

CAMCO

Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company

CBRT

Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey

CCCC

China Communications Construction Company

CCP

Chinese Communist Party

CIC

China Investment Corporation

CIMC

China International Marine Containers

CMG

China Merchants Group

CMP

China Merchants Port

CMPH

China Merchants Port Holdings

COSCO

China Ocean Shipping Company

CPL

COSCO Pacific Limited

CSPL

COSCO Shipping Ports Limited

CSSC

China State Shipbuilding Corporation

CTT

Container Terminal Tollerort

CXIC

Changzhou Xinhuachang International Containers

EIA

Environmental impact assessment

ENISA

The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity

FDI

Foreign direct investment

FEIR/IOBE

Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

5

HHLA

Hamburger Hafen und Logistik

HPCS

Hellenic Port Community System

HRADF/TAIPED

Hellenic Republic Asset Development Fund

ICBC

Industrial and Commercial Bank of China

ICT

Information and communication technologies

M&A

Mergers and acquisitions

MENA

Middle East and North Africa

MEP

Member of the European Parliament

MSC

Mediterranean Shipping Company

NATO

The North Atlantic Treaty Organization

NIS

Network & Information Systems

OOCL

Orient Overseas Container Line

OSCE

Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe

OSINT

Open-Source Intelligence

PCDC

Piraeus Consolidation & Distribution Centre

PCT

Piraeus Container Terminal

PEARL

Piraeus-Europe-Asia Rail Logistics

PLAN

The People's Liberation Army Navy

PPA/OLP

Piraeus Port Authority

SASAC

State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State

Council

SEIA

Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment

SIPG

Shanghai International Port Group

SOE

State-owned enterprise

TEN-T

Trans-European Network for Transport

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

7

LIST OF FIGURES

Figure 1: China’s acquisitions and announced greenfield investment projects in the maritime

sector infrastructure of the EU and its Neighbourhood 13

Figure 2: Number of jobs created, and capital pledged in the announced greenfield

investment projects in the maritime sector infrastructure of the EU and its

Neighbourhood by China, 2004-2021* 14

Figure 3: CMP and COSCO investments in European ports 15

Figure 4: COSCO’s protected home market advantage 18

Figure 5: COSCO’s vertically integrated value chain 19

Figure 6: COSCO Shipping Lines - NET Feeder Route 36

Figure 7: Map of Piraeus Port 50

LIST OF TABLES

Table 1: Value of acquisitions in the maritime infrastructure sector of EU and its

Neighbourhood by Chinese companies 47

Table 2: Pledged capital in announced greenfield investment projects in the maritime

sector infrastructure of the EU and its Neighbourhood; EUR m 48

Table 3: Mandatory Investments in the Port of Piraeus 49

Table 4: PPA/OLP Board of Directors 49

Table 5: Gross throughput volume of Kumport Terminal 50

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

8

EXECUTIVE SUMMARY

• This study identifies 24 Chinese acquisition deals and 13 announced greenfield investment

projects in European maritime infrastructure from 2004 to 2021. Acquisitions accounted for the

bulk of the capital invested – in total, according to our calculations, their value exceeded EUR

9.1bn, while the value of the capital pledged in the greenfield projects was about EUR 1.1bn.

• Investment activity by Chinese companies in the maritime sector subsided noticeably in 2020-

2021, probably reflecting the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and ‘zero-COVID’ policies, and

also the introduction of stricter FDI screening mechanisms in the region.

• China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) and China Merchants have been the leading

investors. Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Company Limited (ZPMC) is the main supplier

of ship-to-shore cranes for European ports. Chinese state-owned enterprises (SOEs) involved in

European maritime infrastructure benefit from a protected home market advantage and a

vertically integrated value chain under the ownership of the State-owned Assets Supervision

and Administration Commission (SASAC) – these facilitate anti-competitive market share

expansion in Europe and risks concerning common market dependency on Chinese providers.

• The analysis of the three case studies - two in EU Member States and one in a EU candidate

country - of the Port of Piraeus (Greece), the Port of Hamburg (Germany) and the Kumport

Terminal (Turkey) show that Chinese investments can bring benefits such as upgrades and

expansions of port capacity (i.e. at Piraeus and Kumport). However, of the cases analysed, only

at the Port of Piraeus has this led to a substantial increase in transit and shipping. The Kumport

Terminal has had a disappointing performance and is operating below its capacity.

• The risk assessment analyses five types of risk: EU-level dependency risk; individual

dependency risk of each case; coercion and/or influence risk; cyber/data risk; and hard security

risk. The analysis highlights that economic coercion and cyber/data security risks are higher

and thus require more attention by the EU and Member States both in terms of preparedness

and awareness.

• Awareness of and capacity to deal with cyber/data risk is identified as the most urgent issue

where the EU and its Member States have poor capabilities. Cyber/data risks will quickly

become more widespread as the digital transition, application of 5G, use of sensors, etc.

develop in the shipping and port operation industries.

• The study shows that investments in one European maritime infrastructure increase the risks

for the whole of the EU. The risk increase appears to be proportional to the investment: the

larger the shares owned by a Chinese enterprise of a European maritime infrastructure, the

higher the risks and their consequences.

• The study notes that risks arise from the deliberate strategy by China to leverage its

investments in European maritime infrastructure to its own advantage, and as a result of

conflict scenarios (i.e. the Taiwan conflict, or disputes between the EU and/or Member States

and China).

• Finally, the risk scenarios envisaged in this study indicate a complex situation that is neither

‘business as usual’ nor ‘apocalyptic sensationalism’. Some risks are likely to require monitoring

and stronger enforcement of current rules, others will need moderate change or co-ordination

between the European Institutions and Member States, and yet others will demand more

complex solutions.

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

9

• Data and analysis of Chinese presence in cyber/data management in ports is poor and so is the

analysis of related risks. Further research to collect data on the risks of Chinese companies’

involvement in cyber and data security in critical infrastructures would provide a strong basis

to inform Member States and develop related policies.

• The study outcomes suggest that Member States carry out a risk assessment of China’s

involvement in their maritime infrastructures that includes the impact on labour and the

environment, as well as on dependencies. An assessment of bottlenecks in the shipping of

goods from China to Europe that considers transshipment is missing. Following such

assessment, redundancies and contingency plans should be created to prepare for a conflict

with China. An early warning system should be established for the risks that require monitoring

and according to the methodology proposed in this study.

• A proposal for a European maritime cabotage law needs to be developed. An EU solution

already exists for air and land, but not for the maritime sector. As such, EU solutions for air and

land provide the basis to adopt a pan-EU maritime cabotage law that could apply to non-EU

shippers.

• Findings suggest a move toward the Europeanisation of screening of inbound investments.

The European Parliament should use the opportunity provided by the review of the existing EU

regulation on screening FDI

1

to propose a strengthening of the role of the EU in not only

screening but also blocking Chinese investments in critical infrastructures. Maritime critical

infrastructure is an area where the decision of one Member State impacts all Member States,

and it could be a pilot case to advance the Europeanisation of FDI screening in critical

infrastructures. This could be limited to majority shareholding of Chinese enterprises, leaving

decisions on minority shareholdings in the hands of Member States.

• To mitigate cyber and data security risks, guidelines on dealing with high-risk actors, such as

data-sharing best practices, should be published, then a regular (six-monthly and then annual)

review of progress with annexed transparency and reporting requirements should be ensured.

The initial report should map existing European ports that use Chinese software and/or data

management platforms and the data being collected and transmitted via these.

1

Regulation (EU) 2019/452 of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 March 2019 establishing a framework for the screening of

foreign direct investments into the Union.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

10

1. INTRODUCTION

1.1. Scope of the study

Economic relations between the EU and the People’s Republic of China (hereafter China) have been

dynamically developing over the past two decades. Following China’s remarkable economic ascent,

the country has become the EU’s third-largest export destination and its largest source of imports.

Beyond trade, China has emerged as a major source of global FDI flows, including in the EU. Although

total Chinese FDI stocks in Europe remain small compared to other investment partners

, they have

relevance in several sectors with strategic importance. As economic security risks (e.g. critical

dependencies) stemming from foreign ownership become more apparent, the EU has committed to

de-risking to a more resilient and autonomous economic structure, particularly vis-à-vis China, which it

considers ‘a partner, a competitor and a systemic rival’.

The EU framework for FDI Screening, introduced in 2020, aimed to create a co-operation mechanism

for information sharing on FDI across EU Member States, and between Member States and the

Commission. The Regulation is up for review in 2023. Furthermore, in 2022 the EU approved new

rules

for protecting the EU’s essential infrastructure, according to which Member States should adopt

national resilience strategies and cross-border communication should take place through designated

points of contact.

One critical area that is addressed by the Regulation and in which Chinese firms have been

accumulating growing stakes – not least through the flagship Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) – is transport

infrastructure. Maritime ports form an indispensable component of this, serving as vital gateways for

international trade and global connectivity. In this regard, the ownership structure of EU’s ports

deserves special attention, especially as, over the past decade, Chinese state-owned firms have

acquired stakes in 15 European ports – including in Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Malta,

the Netherlands and Spain in the EU, as well as in EU Neighbourhood states such as Turkey.

The security risks associated with Chinese investments and ownership of European ports have been

debated at national and international levels and have spurred increased scrutiny and awareness.

However, an analysis of critical infrastructures, including transport infrastructures, through the lens of

de-risking is yet to be undertaken.

2

Therefore, the main scope of this study is to carry out a thorough

risk assessment that focuses on risk scenarios associated with Chinese involvement in the EU’s maritime

infrastructure via FDI. Although the scope of this study’s risk assessment is narrow, the assessment can

then be replicated to other infrastructures and other sectors to obtain a more comprehensive picture

of the risks posed by Chinese investments in the EU.

Against this backdrop, this study aims to provide policy recommendations to guide EU decision-

making, with particular attention to the competences of the European Parliament. To this end, the

study is divided into three sections. Section 1 is an introductory chapter, providing a background

regarding the Chinese position as a maritime power in investments and shipping. In this section,

detailed data on Chinese investments in the maritime sector in Europe

are identified, collated and

descriptively analysed to understand the magnitude and the trends in these FDI flows. Section 2

provides a case study-based risk assessment of Chinese investments in the EU maritime infrastructure

to provide the necessary depth to our analysis. The study assesses the risks using a framework designed

by the National Risk Assessment of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 2022 and adapting it to the

requirements of this study by focusing on five key risk areas. The framework is applied generally to the

EU, as well as to three case studies: the Port of Piraeus in Greece, the Port of Hamburg in Germany, and

2

In this study, de-risking is used with the meaning of managing and decreasing risk.

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

11

the Kumport Terminal in Turkey. This section also considers the implications for the broader European

context beyond the EU and its Neighbourhood states. Finally, Section 3 summarises the study's main

conclusions and presents evidence-based and actionable policy recommendations to mitigate and

manage the identified security risks.

1.2. Overview of China as a maritime power

At present, 90% of global goods traverse through shipping routes. According to the World Trade

Organization (WTO), in 2020 shipping accounted for 53% of the total value of China’s trade. Within its

borders, China boasts the highest concentration of shipping ports within a single country, with seven

of these ports among the world's busiest.

Outside China’s borders, investments in ports have constituted a significant facet of President

Xi Jinping's ambitious Belt and Road Initiative.

3

China’s global maritime investments have predominantly been carried out by the state-owned

enterprises China Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) and China Merchants Group (CMG), and by

CK Hutchison Holdings, a private enterprise based in Hong Kong. However, other entities have also

played their part in bolstering the global presence of Chinese firms within port operations. Prominent

among these are the

Shanghai International Port Group (SIPG) and port authorities such as

Qingdao Port. China Communications Construction Company (CCCC) has occasionally put forward

investment proposals concerning critical maritime infrastructure, although its activities predominantly

focus on investments and construction in other sectors. Among the entities listed, COSCO notably

holds the distinction of being a pivotal container shipping company, and is thus uniquely positioned,

with the capacity to re-route containers to alternative ports directly.

Beyond direct investments in port facilities, China has emerged as the predominant global

manufacturer of essential equipment. Impressively,

China's production encompasses 96% of the

worldwide share of shipping containers and 80% of ship-to-shore cranes, and it claimed 48% of the

world's shipbuilding orders in 2022.

Chinese firms also deliver indispensable services critical to the

modern functioning of ports. For instance, Shanghai Zhenhua Heavy Industries Company Limited

(ZPMC) is the leading supplier of ship-to-shore cranes and it

has offices in some of the European cities

that host investments by COSCO: Rotterdam (the Netherlands), Valencia (Spain), Hamburg (Germany)

and Savona (Italy), but is active in most European ports, including in

Belgium, Greece and France.

In early 2023 The Wall Street Journal published an article arguing that the sophisticated technology of

ZPMC’s cranes allowed the equipment to collect data on the origin and destination of containers. This

was not the first occasion on which concerns had been raised about Chinese companies’ data

management systems for ports within their investment purview. The lack of clarity over the capabilities

of technologies present in ship-to-shore cranes highlights an important but overlooked aspect related

to the presence of Chinese companies in the European maritime transport sector, that of cyber- and

data security. The key risks centre on the potential access that Chinese companies might gain to

sensitive data, both civilian and military. An example of such exposure is the signing of a

co-o

peration

agreement between Portbase, a Dutch company that improves communication and data exchanges

between ports and inland infrastructures, and Logink, a Chinese company that operates in the same

sector, in 2019. China’s Data Security Law and the National Intelligence Law, furthermore, require data

to be shared with the Chinese government if required.

3

Not all investments amount to full ownership.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

12

1.3. Specificities of Chinese direct investments

Attention towards Chinese investments in critical infrastructures and the associated risks has been

increasing since the mid-2010s. Several factors contribute to Chinese investments being seen to

challenge the EU’s openness, economic resilience and security, more so than for investments

originating from other major sources. The three primary reasons are:

1. State ownership of investing companies. The fact that many Chinese enterprises investing

abroad are state-owned raises questions about their autonomy from the government and their

integration within the broader system. While acknowledging the potential commercial

motivations behind these investments, it is essential to recognise that Chinese SOEs might also

pursue objectives beyond mere profitability, unlike their European equivalents with fiduciary

responsibilities to shareholders. These objectives are often spelled out in China’s strategic

documents; they can range from expanding China's influence within a vital sector for global

trade to acquiring strategic assets that bolster China's geopolitical standing. This is especially

true since Xi Jinping came to power in 2013, as he has reversed the direction of SOE reform and

has instead called for 'better, stronger, bigger' SOEs to advance Chinese interests

. The nature

of SOEs urges a comprehensive analysis encompassing both commercial and strategic

considerations.

2. Magnitude and expansion of Chinese investments. The remarkable scale and rapid

expansion of Chinese investments within the sector have been exemplified by prominent

Chinese enterprises spearheading numerous acquisitions abroad throughout the 2000s, with

a particular surge in activity during the 2010s. This surge has raised concerns that Chinese SOEs,

and to some extent China as a whole, are progressively establishing dominance within the

sector, leaving limited room for competitors. The apprehension centres on the emergence of

issues such as unfair practices, market distortions, unfair competition and the absence of a level

playing-field. Chinese SOEs possess inherent advantages rooted in their national ecosystem,

which they leverage to outperform their counterparts (see Section 2.1).

3. Political and security implications of Chinese investments. The notion of China as a

systemic rival reinforces the urgent need to consider the security implications associated with

investments from a country that has exhibited deficiencies in the rule of law and in

fundamental principles such as transparency and labour rights. Moreover, as geopolitical

tensions between the United States and China escalate, China has embraced strategies

including economic coercion

4

and other forms of influence. These strategies raise pertinent

questions concerning the political and security ramifications of Chinese companies' presence

within critical infrastructures that form the bedrock of our societies' functioning.

1.4. Chinese investments in the maritime sector in Europe

This section analyses the data on Chinese direct investments in the EU’s maritime transport

infrastructure. The data coverage of China’s investment activity abroad is somewhat patchy. Hence,

data from multiple sources are consolidated to present the most comprehensive picture possible of

the Chinese investment presence in the EU’s maritime sector. We convert USD-denominated values

into EUR-denominated ones using average annual and monthly USD/EUR exchange rates reported by

the European Central Bank.

4

Using economic means and lever to achieve political goals. China's economic coercion (europa.eu)

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

13

Figure 1 shows the investment activity of Chinese companies in the maritime transport sector of the

EU and its Neighbourhood

5

based on the data collected. During 2004-2021, a total of 24 acquisition

deals, and 13 announced greenfield investment projects can be identified in the sector, with China

Ocean Shipping Company (COSCO) and China Merchants being the leading investors. Acquisitions

accounted for the bulk of the capital invested – during 2004-2021 their total value exceeded

EUR 9.1bn,

6

while the value of the capital pledged in the announced greenfield projects stood at about

EUR 1.1bn. This is in line with the general strategy of Chinese investors till recently to prefer cross-

border M&A to access existing strategic assets as well as technologies, and quickly expand their market

share. In 2020-2021 investment activity by Chinese companies in the sector sharply subsided, probably

reflecting the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and 'zero-COVID' policies on the Chinese economy,

as

well as the introduction of stricter FDI screening mechanisms in the region. More detailed information

on the investment projects can be found in

Table 1 and Table 2 in the Annex.

Figure 1: China’s acquisitions and announced greenfield investment projects in the

maritime sector infrastructure of the EU and its Neighbourhood

Number of deals Value of investment, EUR m

Sources: fDi Markets; China Global Investment Tracker; ECFR China-EU Power Audit Key Deals 2005-2017; China Overseas

Port Project Dataset 1979-2019; https://www.truenumbers.it/cina-porti-europa/; authors’ calculations.

* In 2010 and 2016 there were deals with unknown value: in 2010 Shanghai International Port Group acquired 25% of

Zeebrugge Port; in 2016 ICBC acquired a stake in Antwerp Port.

According to fDi Markets data

7

, China’s greenfield investment projects in the sector generated around

3,200 jobs during the entire period, most of them in Greece in the projects related to Piraeus port in

2013 (700 jobs), 2016 (1,255 jobs), and 2019 (507 jobs) – see Figure 2. Spain comes second in terms of

jobs created and capital pledged, but the numbers do not even come close to those recorded in Greece.

5

The EU Neighbourhood is defined here as Western Balkan countries, Georgia, Moldova, Turkey and Ukraine.

6

There is no available information on the value of two acquisition deals.

7

fDi Markets, a Financial Times dataset on cross-border greenfield investments that covers all countries and sectors worldwide. It contains

information on various characteristics of the announced greenfield investment projects, such as sector of the mother company and an

affiliate that is being created, value of investment projects and estimate of the jobs being created.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Greenfield investment Acquisitions

0

200

400

600

800

1000

1200

1400

1600

1800

2004

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010*

2012

2013

2014

2015

2016*

2017

2018

2019

2020

2021

Greenfield investment Acquisitions

2008 - 3935

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

14

Figure 2: Number of jobs created, and capital pledged in the announced greenfield

investment projects in the maritime sector infrastructure of the EU and its

Neighbourhood by China, 2004-2021*

Number of jobs Value of investment, EUR m

Source: fDi Markets, authors’ calculations.

* The Hamburg port investment was originally planned to be EUR 100m, but has since been reduced in scale, with a decrease

in the shareholding to 24.99%. The revised investment value is not yet known and therefore not accounted for in the graph

above.

Chinese SOEs have established a presence in 15 distinct EU ports in countries including Greece, Malta,

Italy, Spain, France, Belgium, the Netherlands and Germany. China controls about 10% of European

throughput (see

Figure 3)

8

. However, not all of these investments entail a majority stake or full

ownership. In many instances where a majority shareholding or ownership is achieved, the investment

is concentrated within a specific terminal within the port, rather than encompassing the entire port

complex. A notable exception that diverges from this pattern is the Port of Piraeus in Greece, one of the

case studies we analyse, where COSCO holds majority shares in the port and maintains complete

ownership of the container terminal.

The predominant period for these investments in European ports dates from 2013 to 2020. Because

China’s economy has been slowing down, China's overseas investments in large infrastructural projects

have been scaled back in some destinations. Investments have been further negatively impacted as a

growing array of EU countries have begun instituting policies to scrutinise and potentially impede FDI.

This trend has not spared investments in ports, although sporadic but pertinent investments continue

to arise. One such recent instance involves

COSCO's acquisition of stakes in the Container Terminal

Tollerort (CTT) within the Port of Hamburg, Germany, a transaction finalised in 2023.

Many of the European ports in which Chinese enterprise have a stake are part of the EU’s core trans-

European transport network policy (TEN-T). The scope of the TEN-T is to develop

“coherent, efficient,

multimodal, and high-quality transport infrastructure across the EU” by connecting different means of

transportations in one network. The aggregated Chinese presence in these ports in nodes of the core

TEN-T carries important implications for the resilience of the network that range from minor disruptions

in one node (i.e., in a small terminal such as the Tollerort terminal in the port of Hamburg) to disruptions

to the whole core network (i.e., if all Chinese investments in EU ports are leveraged and/or suspended

at the same time). Section 2 of the study will further elaborate on these cases and on intermediary

steps.

8

Other investments in Europe by Chinese companies that are not SOEs include two by Hutchison Ports Holdings (HPH): one in Poland, in

Wolny Obszar Gospodarczy (WOG), a terminal at the Port of Gdynia; and one in Sweden, in a container terminal within Stockholm Free

Port.

0

50

100

150

200

250

300

2350

2400

2450

2500

0

25

50

75

100

125

825

850

875

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

15

Even though TEN-T connects multiple European ports, and other transport infrastructures in the single

market, the EU maritime cabotage regulation o

nly “ensure(s) that maritime transport services within a

Member State can be offered by companies of other Member States”. Transport services are still

registered and regulated at national level not at EU level, meaning that different Member States have

different levels of openness and restrictiveness vis à vis non-European vessels. That is not the case for,

for example,

air tran

sports. Furthermore, due to the lack of a common market maritime cabotage, non-

EU ships can move from one Member State to another to avoid the cabotage law of a specific Member

States and can still interact with the common market at each port.

Figure 3: CMP and COSCO investments in European ports

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

16

2. CASE STUDIES AND RISK ASSESSMENTS

A general and case study-based risk assessment is conducted in this study, in order to provide an

in- depth evaluation of the Chinese investment presence in European maritime transport

infrastructure. The risk assessment framework applied adapts the methodology from the

National Risk

Assessment of the Kingdom of the Netherlands 2022 compiled by the National Network of Safety and

Security Analysts, which follows the main methodology usually adopted in risk analysis by other

countries and in the private sector. The purpose is to evaluate various risks across two primary

dimensions – likelihood and impact – across different potential scenarios.

Risks are categorised into five main groupings, which are most relevant to critical transportation

infrastructure:

1. EU-level dependency risk (additional dependency risks to total single market dependency

levels) – How dependent is the single market on the Chinese investment in the port infrastructure?

2. Individual dependency risk (dependency risks for an individual investment) – How dependent

is the host country on the Chinese investment in the given port infrastructure, including at the

‘ecosystem’ level?

3. Coercion and/or influence risk – Does this investment meaningfully raise the risk of Beijing’s

coercion/influence over the country’s and EU politics, actively or passively?

4. Cyber/data risk – Does Chinese investment/participation in this infrastructure/project create new

cyber threats to critical infrastructure and/or raise data security/privacy risks?

5. Hard security risk – Does the investment create traditional national security risks, mainly related to

use by China’s military or to its ability to inhibit or undermine European security?

These five risk groups are used as lenses to examine the risk to critical transportation infrastructure

across the EU and countries in the European Neighbourhood. To enhance the comprehensive

assessment of risks, three case studies delve into specific risk scenarios that might emerge as a result

of Chinese investments in, or utilisation of, critical maritime infrastructures across Europe. Each scenario

is subjected to a thorough analysis, evaluating its likelihood of occurrence and potential impact. The

findings of this assessment are subsequently organised into a table, plotting the scenarios based on

their likelihood and impact levels. This visual representation aids stakeholders in promptly gauging

which risks necessitate immediate attention and action and, in contrast, which require lighter

monitoring and contingency planning.

The following three case studies are examined through the lenses of the risk groupings:

• The Port of Piraeus, Greece

• The Port of Hamburg, Germany

• Kumport Terminal, Turkey

The selection of these cases illustrates distinct scenarios involving Chinese SOEs and their investments

within European ports. These cases encompass a spectrum, ranging from an instance where a Chinese

SOE holds full ownership of container terminals plus a majority share of the port authority in an EU port

(Port of Piraeus, Greece) to a case with a minority shareholding in a single terminal within an EU port

(Port of Hamburg, Germany). The selection includes a case study from an EU candidate country

(Kumport Terminal, Turkey).

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

17

2.1. EU-level dependency risk assessment

Background

Individual investments in European maritime infrastructure generate varying levels of dependency on

a single-site or whole-of-country basis. Nevertheless, each investment also adds to a net dependency

risk at the EU level. This section looks into the risks and opportunities that the collective footprint of

Chinese investment in European ports and shipping operations has on the common market.

Importantly, this big-picture assessment provides context for the subsequent case studies that look at

individual cases in more detail.

For acquisitions of existing infrastructure, the shareholders in ports receiving investment from Chinese

firms are the most immediate beneficiaries, when that investment surge is paid out through dividends.

Beyond that, the port operators sometimes use the raised capital to pay off liabilities or reinvest it into

the port to upgrade or expand operations.

However, the longer-term benefits, including through M&A and greenfield investment, can be

considerable

9

– but only to the degree that the acquisition meaningfully expands trade flows and/or

boosts the efficiency of port operations. As such, if the acquisition expands the capacity of total import

and export potential, which is then utilised, the benefits at the EU level are significant. In other words,

if investment and increases in shipping services – which boost ‘supply’ – are met with new demand as

a result of, for example, lower prices or easier/better access to overseas markets, the benefit is notable.

However, if this only manages to redirect existing demand to use one port over another, the benefits

are negligible if not net-zero, and only materialize at the local level.

For example, suppose that the investment in the Port of Hamburg lowers prices and improves access

to foreign markets to the extent that it leads companies in the hinterland to increase production for

export. In that case, the benefits are considerable: more production means higher employment,

increased demand for rail, barge and truck services to get products to the port, and more employment

at and a better return on investment (ROI) from the port itself. But suppose that the investment and

increased traffic in Hamburg only lead to already existing trade flows redirecting to Hamburg, and away

from Rotterdam and Gdansk. In that case, the net benefit is marginal, even though it is good for the

logistics chain leading to the Port of Hamburg, albeit at the expense of Rotterdam and Gdansk.

Downside of China-sourced investment in European maritime infrastructure

The primary downside to the expansion of the market share of Chinese SOEs such as COSCO and CMG

in European shipping markets is that higher market share also means higher dependency risks. Many

in Europe learned this lesson the hard way after Russia invaded Ukraine and they found themselves

dependent not only on oil and gas infrastructure controlled by Russian firms, such as Nord Stream, but

also on the oil and gas that flowed through it. Russian market share in those countries’ energy mix

quickly translated into dependency on Russia that could be weaponised at the worst possible moment.

Even in circumstances falling short of a Russia-like scenario, dependency concerns are at the core of de-

risking efforts – many risks exist only because of the level of reliance on China as provider of certain

goods. The political/geopolitical connection, therefore, has already been made for China-dominated

products such as refined critical raw minerals, solar panels and legacy chips. However, services such as

port operation and shipping services, which underlie the global value chains that Europe heavily relies

on, are often overlooked.

9

Such as investments to expand throughput capacity, which COSCO made in Piraeus.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

18

Although there is considerable risk that COSCO will be able to, over time, take market share from

European shippers owing to the unfair advantages (outlined below) that it enjoys, European shippers

do enjoy a substantial head start. Four of the five largest container shippers (measured by throughput

)

are European; the other is COSCO. That said, COSCO’s global market share in container shipping has

grown steadily, from

4.5% in 2013 to 10.8% in 2023.

COSCO has achieved rapid and sustained growth, and its expansion is fuelled heavily by advantages it

enjoys in its home market, which can be projected outward. However, at its core, COSCO should be

understood to be profoundly unlike its European competitors. Unlike the publicly listed European firms

it strives to outcompete, COSCO is legally bound to advance the strategic goals of its country’s

government and it rejects the fiduciary responsibilities that others are bound by to their shareholders.

Instead, COSCO can, to the degree that Beijing wants it to, cut into its margins in order to boost its

market share.

COSCO benefits from extensive protectionism at home that enhances its EU market share growth

In its home market, COSCO benefits from extensive protection through

extremely restrictive maritime

cabotage law (see Figure 4). Foreign shippers can engage in standard international shipping at Chinese

ports. However, they are banned from international relay

10

(except for one marginal pilot programme

limited to a few ports) and domestic/hinterland shipping. To transship or carry out inland shipping,

China requires that vessels be Chinese-flagged and owned and operated by a Chinese company. As

such, Hapag-Lloyd or MSC would be able to bring goods to and from the Port of Shanghai, but even if

they invested in a local subsidiary and had Chinese-flagged vessels, they could not transship goods

from Qingdao through Shanghai or bring goods from Wuhan down the Yangtze to be shipped from

Shanghai to foreign markets.

Figure 4: COSCO’s protected home market advantage

Source: MERICS

10

Relay is a container transfer between two ships controlled by the same carrier. In case of international relay, coastal relay of international

cargo is done by a foreign carrier.

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

19

Meanwhile, COSCO can and does engage in all types of shipping in Europe, directly or through

subsidiaries. Its investments in the Port of Piraeus are explicitly for transshipping purposes, as is the

case in other ports such as Hamburg and Rotterdam, while subsidiaries like COSCO (Europe) and

Diamond Line are developing feeder services using locally flagged vessels to perform domestic and

hinterland shipping.

This means that COSCO can compete for and acquire market share in Europe in a way that European

shippers cannot in China, thanks to this protected home market advantage

. That may sound like a

market access and reciprocity issue. However, the unequal playing-field that favours COSCO means

growing market share for that firm, shrinking market share for European shippers, and hence greater

European dependence on COSCO.

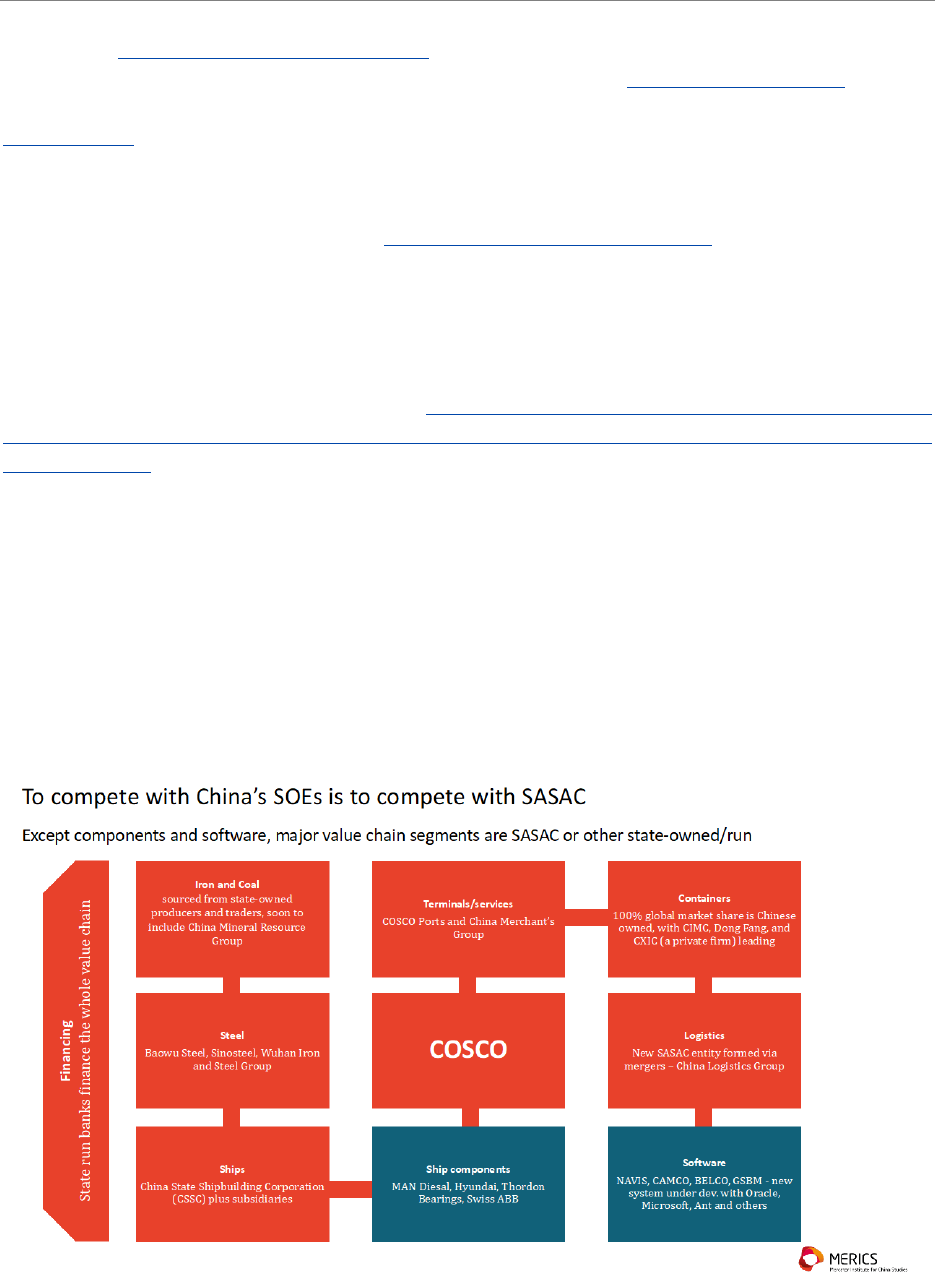

COSCO’s vertically integrated value chain further empowers its ability to seize market share

Competing against COSCO for market share is

not just a matter of competing with COSCO – it is about

competing with the State-owned Assets Supervision and Administration Commission of the State

Council (SASAC). This holding company controls and manages China’s 97 centrally owned SOEs.

Much of the value, up and downstream in COSCO’s value chain, is also SASAC-owned or state-owned

by different entities. Upstream, more and more of COSCO’s ships are made by CSSC, which gets its steel

from Baowu and other SOEs, which themselves get their iron ore and coal from state-owned minders

and traders – all under SASAC. Downstream is a similar story. Many of the terminals COSCO uses are

owned by COSCO or CMG; the containers are all made in China, primarily by SOEs; and a key logistics

service provider/co-ordinator is also SASAC-owned. All of these entities are also mainly financed by

China’s state-run banks.

Figure 5: COSCO’s vertically integrated value chain

Source: MERICS.

Because of its robust competition law, such a vertically integrated value chain would be impossible

within the EU. However, that competition law does not apply to the whole value chain in China but

only to the ‘point of contact’ in COSCO itself through its activities in the EU. But that does not stop

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

20

the obvious and anti-competitive advantages that COSCO enjoys at home from causing distortions in

the common market.

Leveraging those advantages, like leveraging its protected home market advantage, gives COSCO

a clear edge when competing for market share in Europe and beyond, thus exacerbating dependency

risks.

Generally, the individual dependency risk will depend heavily on how much market share in European

ports and shipping markets Chinese firms such as COSCO and CMG can acquire. The higher the market

share, the greater the dependency on Chinese providers and the less capacity European competitors

(which presumably would have lost market share and become smaller) would have if they needed to

fill in as alternate operators and providers.

In a scenario in which COSCO and CMG only marginally increase their market share in the EU over the

coming decade, perhaps owing to economic slowdowns in China that lead Beijing to call on SOEs to

prioritise boosting employment over global expansion, the risk is limited. China’s SOEs are often

tapped to fulfil such social stability roles during economic headwinds. China’s economy is struggling

to get back up to speed post-COVID, making this scenario more possible than in previous years. That

would mean diminished benefits from investment and from potential increases in total trade, but from

a risk mitigation perspective, this scenario is optimistic.

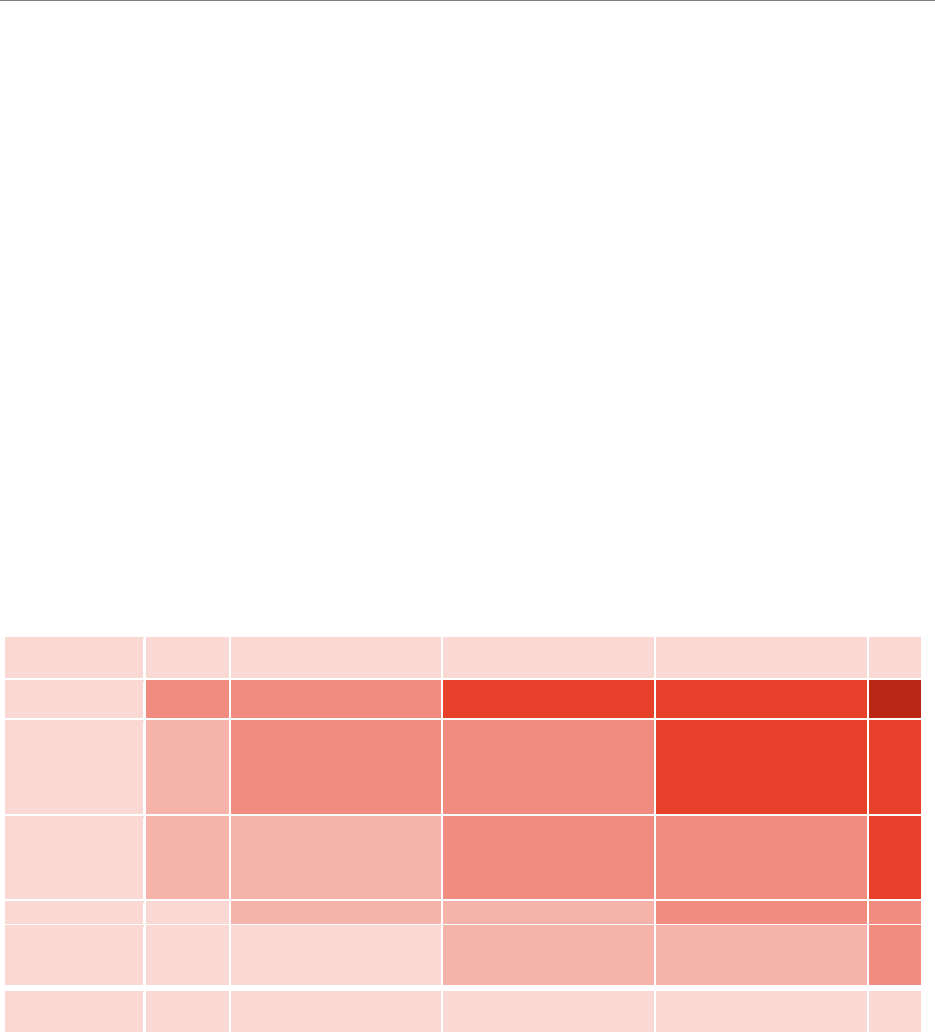

Risk assessment: EU-level dependency risk

Impact level /

Likelihood

Catastrophic

Very serious

China's port and shipping firms

drastically increase market

share in the EU and heavily

displace European firms

Serious

China's port and ship-ping

firms significantly increase

market share in the EU and

displace European firms

Substantial

Limited

China's port and shipping firms

marginally increase market

share in the EU

Very

unlikely

Unlikely Somewhat likely Likely

Very

likely

Source: Authors’ analysis.

If COSCO and CMG manage to increase their investments and market shares in Europe at a pace

comparable to that achieved in the past – albeit likely less on the investment side, which is now subject

to greater scrutiny – they would be doing so in ways that come at the expense of European shippers’

market share. Assuming no significant changes in the EU vs member-state dynamic, COSCO and CMG

may continue to play off Member States against one another to maintain access and expand market

share over the coming decades. This outcome would not only enhance the dependency risks for the

EU but would also generate more significant exposure to other risk types, such as influence/coercion

potential – after all, the ability to influence or coerce is intrinsically tied to how much could be at stake

if Beijing attempts to weaponise dependencies.

Finally, there is a scenario in which European policy makers need to turn to Chinese firms for capital

injection, as many did during the fallout years after the global financial crisis. Were this to occur, COSCO

and CMG would seize the opportunities to invest in more ports and expand their shipping market

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

21

share. This scenario is unlikely, however, as an economic crisis severe enough to push European

governments to take such steps would be likely to bring down China’s economy as well – and, with

current debt levels, Beijing could not again disburse the scale of stimulus it did in 2008. However,

in such a wildcard scenario, dependency risks would grow considerably.

2.2. Piraues, Greece

Background

In November 2008 the Greek government and China’s COSCO Pacific (subsequently COSCO Shipping)

signed a concession agreement worth EUR 831.2m

. The deal covered two of the three piers of the

Piraeus port, which have been since managed by a COSCO subsidiary, Piraeus Container Terminal (PCT).

The initial duration of the agreement was 35 years, but in 2012 it was extended until February 2052.

In 2016, at the height of Greece’s fiscal and economic crisis, COSCO obtained a 51% majority stake in

the Piraeus Port Authority (PPA/OLP) for EUR 280.5m, plus EUR 88m in an escrow account.

11

Under the

terms of the deal, COSCO had the right to claim an extra 16% of the PPA/OLP stock five years later, if

within that timeframe it had completed a set of 11 mandatory investments worth EUR 294m in the

infrastructure of the port (see Annex Table 3). Under the 2016 agreement, COSCO reserves the exclusive

right to use and exploit the land and infrastructure inside the port area.

In August 2021 the Greek government agreed to give COSCO the extra 16% of the PPA/OLP stock, even

though the Chinese company still needed to complete the mandatory investments set out in the 2016

agreement. COSCO undertook to complete the mandatory investments by 2026 or, in case of further

delays caused by force majeure, by 2031.

11

Escrow account is an account opened by a third party for the purposes of holding cash on behalf of two or more contracting parties until

certain agreed contractual conditions for release of the funds from the account have been met.

https://uk.practicallaw.thomsonreuters.com/0-107-6230?transitionType=Default&contextData=(sc.Default)&firstPage=true

SUMMARY OF KEY MESSAGES

• The Port of Piraeus is seen by China as a valuable asset in inter-regional supply chains.

A shutdown or a change to the management of the facility would be likely only under

extreme circumstances.

• COSCO’s presence is perceived as beneficial to the port and to Greece, although this is

based primarily on Chinese narratives. An impact assessment of the investment has

never been considered by Greek authorities.

• A major crisis with China would have a very serious impact – primarily on the Piraeus

economic ecosystem and to a lesser extent on the overall Greek economy – and could

lead to coercion on the part of Beijing.

• COSCO’s presence next to critical civilian and military infrastructure is highly

problematic, in terms of cyber risks and potential sensitive data leaks.

• Greece’s level of preparedness in view of a major crisis with China is low. This applies

to COSCO’s investment in the Port of Piraeus as well.

• A thorough risk assessment of COSCO’s investment requires close co-ordination

with Western partners in terms of technical assistance.

• Similarly, the creation of a crisis management mechanism and mitigation of various

potential risks are possible only in concert with EU and NATO partners.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

22

Governance structure

The Port of Piraeus has the following governance structure:

Piraeus Container Terminal (PCT), a 100% subsidiary of COSCO, has been operating Piers II and III at the

Port of Piraeus since 2009. PCT and PPA/OLP are separate legal entities, but are both managed by

COSCO.

Based on the agreement renegotiated in 2021, COSCO now holds a 67% stake in PPA/OLP. The Hellenic

Republic Asset Development Fund (HRADF/TAIPED), Greece’s privatisation agency, holds roughly 7%,

while the remaining 26% stake is in the hands of investors who have bought PPA/OLP shares through

the Athens Stock Exchange. If COSCO’s stake becomes even higher than 67%, this will further

strengthen its hand in managing PPA/OLP. In theory, if HRADF/TAIPED sells its remaining shares and

COSCO buys the shares of the remaining investors, the Chinese company's stake in PPA/OLP could

reach 100%.

The PPA/OLP Board of Directors (BoD) comprises six Chinese and three Greek members, with COSCO

providing the chairman and the chief executive officer (see Annex Table 4). None of the three Greek

representatives is an executive member of the BoD. The Greek members are: an HRADF/TAIPED

representative; the incumbent mayor of Piraeus; and an honorary president of the International

Maritime Union, a Piraeus-based association of shipping agencies. Notably, the mayor of Piraeus is not

included as an ex officio member, but as an independent individual – and so it is not clear if his position

will be filled upon the expiry of his term of office.

Yet another legal entity, 100% owned by COSCO, is the Piraeus Consolidation & Distribution Centre

(PCDC), a facility providing logistics services at PCT. It handles and stores general/dry cargo,

refrigerated and deep-frozen goods, flammable products, chemicals, etc. While goods are at PCDC,

duties and taxes are not levied on them. A further entity under COSCO’s control is the former Greek

company Piraeus-Europe-Asia Rail Logistics (PEARL). In November 2019, during the state visit to Greece

of Chinese President Xi Jinping, 60% of the stock of PEARL was purchased

by Ocean Rail Logistics, a

100% subsidiary of COSCO.

Benefits drawn from COSCO’s investment

There have been apparent benefits generated since COSCO’s arrival in 2008. Before that, Piraeus was

primarily a passenger port, with a limited container handling capacity (throughput) in the range of

700,000 twenty-foot container equivalent units (TEUs). COSCO’s investment has helped to increase the

container throughput by a factor of eight, to 5.6m TEUs in 2019.

Piraeus port's current throughput is estimated at 7.2m TEUs. The PPA/COSCO management insists on

the construction of Pier IV and seeks to boost the port's throughput to between 10m and 11m TEUs. In

this way, Piraeus could compete on an equal footing with Hamburg, Antwerp and Rotterdam. However,

the Greek authorities have yet to approve this proposal. In the absence of such approval, COSCO is

upgrading the existing facilities through rearrangements within the PPA territory (see Annex Figure 7)

However, the container volume at Piraeus has shrunk from its record high of 5.6m TEUs in 2019. This

can be attributed to two main factors: the negative impact of China’s zero-COVID strategy in 2020-

2022; and a series of strikes at PPA due to disputes between the management and local trade unions.

Tensions peaked in late 2021 after a fatal accident

affecting a worker at Piraeus. As a result, Piraeus has

lost its dominant position in the Mediterranean as a container port and has been overtaken by Tanger-

Med in Morocco and Valencia in Spain.

At present, the Piraeus port is performing very well in terms of passenger traffic, as the tourism boom

in Greece has led to a growing number of cruise arrivals. Additional proposals by COSCO envisage the

construction of four hotels. This reflects the priority given by the PPA/OLP management to Piraeus as

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

23

a passenger home port and a significant destination for cruisers. 2022 was a profitable year for

PPA/OLP, mainly owing to the cruise/ferry traffic through the port.

COSCO has stated that in 2021 its investment had the following impact: the economic value added

corresponded to 0.76% of Greece’s GDP and the jobs created accounted for 0.12% of the country's total

employment. These estimates cannot be confirmed by any other source, as Greek authorities have not

commissioned an impact assessment of COSCO’s investment in Piraeus.

Downside of COSCO’s investment

Several disputes in Piraeus and adjacent municipalities have marred COSCO’s investment.

In particular, in 2020 Piraeus City Council expressed disquiet about the absence of an environmental

impact assessment (EIA) for the construction of a new cruise terminal worth EUR 136m. The project has

now been approved, and a contractor selected by COSCO is building the terminal, but with funding

provided through the EU structural funds.

Although environment aspects are not taken into consideration in the risk assessment of this study,

there have been concerns about the environmental impact of mandatory investments and the need

for adequate environmental impact assessments. For instance, all the local and regional authorities

initially dismissed the Strategic Environmental Impact Assessment (SEIA) submitted by PPA/COSCO. In

2022 Greece’s Council of State ruled that PPA had to approve a comprehensive SEIA before

implementing its expansion plan. The SEIA has now been submitted and approved by Greek

authorities.

In addition, there have been concerns about pollution caused in the port and the city of Piraeus. For

instance, the transportation of debris through the streets of Piraeus increased congestion levels in the

city. This mobilised local activists, who blocked the movement of PPA/COSCO lorries in Piraeus in late

2020. Furthermore, local ship repair businesses have strongly objected to COSCO’s plan to construct a

new shipyard in Perama, to the west of Piraeus. Their grievances have been taken to Parliament by the

opposition.

The official position of the Greek Ministry of Shipping is that such a shipyard, controlled by

COSCO, is not envisaged in the 2016 agreement.

A proposal put forward by COSCO/PPA in 2020 envisaged the creation of an e-platform for the

management of all functions of the port. The so-called Hellenic Port Community System (HPCS) was

opposed by a number of business actors in Piraeus who argued that this would lead to a ‘monopoly on

services’ in the hands of COSCO and open the door to unfair competition by other Chinese companies.

In the end, the Ministry of Shipping announced that it would replace HPCS with a National Integrated

Port Community System controlled by the state and included relevant provisions in a law adopted by

parliament in January 2021.

Initial expectations were that a considerably higher number of jobs would be created. In 2016 the

Foundation for Economic and Industrial Research (FEIR/IOBE) carried out a study which referred to

31,000 potential new jobs, whereas the current level of employment is 4,279 jobs (direct, indirect and

induced). As a large SOE, COSCO benefited from the Chinese state's political support to ensure better

contractual terms. Thus, in early

2015 EU state aid regulators ordered the Greek government to recover

certain illegal fiscal benefits granted to PCT and its parent company COSCO. Under the 2008

agreement, the Greek state had granted COSCO tax exemptions in value-added tax (VAT) and

depreciation obligations, which were more favourable

than Greek entities' standard obligations,

including those of PPA/OLP.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

24

Risk assessment: Piraeus, Greece

Source: Authors’ analysis.

Individual dependency risk

In the event of a major crisis in relations between the EU and Beijing, for example in the case of an

armed conflict over Taiwan or an incident in the South China Sea, the EU is widely expected to consider

imposing sanctions on China. Greece would be likely to follow suit – even if reluctantly.

12

This would

probably lead to reprisals by China.

The Piraeus ecosystem depends entirely on PPA/OLP, and any disturbance in its operation would be

felt immediately. Greece’s growing dependence on Chinese high-tech imports should also be factored

in. For instance, one Chinese solar panel producer

claims up to a 50% share of the Greek market and all

its products are imported via Piraeus. Possible scenarios of Chinese reprisals would include a

suspension of COSCO operations at Piraeus (which would effectively shut down the entire port) and

imposition of restrictions on Chinese exports to Greece.

However, if COSCO were to shut its operation in Piraeus altogether, China would lose – temporarily, at

least – access to ‘the jewel in its BRI crown’

and a significant transshipment hub in the Eastern

Mediterranean and Southeast Europe. Moreover, COSCO does not have another equally well-

developed hub in the Eastern Mediterranean. What Beijing is more likely to consider is imposing

targeted restrictions on strategically important Chinese exports to Greece.

The impact would be severe for the local ecosystem regarding employment and spin-off economic

benefits in the broader area of Piraeus. On a national scale, Greece might face an acute shortage of

equipment for the country’s green transition, e.g. as solar panels, electric vehicles and batteries, etc.

Further, unless COSCO shuts down its operation in Piraeus altogether, Greek authorities will face a

12

Interview with a Greek state official, 14 January 2023.

Impact level /

Likelihood

Catastrophic

Very serious

Individual dependency risk:

Suspension of COSCO

operations at Piraeus

Hard security risk:

COSCO is

activated as a maritime

militia. PLAN uses Piraeus as

an indirect resupply hub

Serious

EU-level dependency risk:

Complete breakdown of

trade through COSCO

Coercion/influence risk: COSCO threatens

to shrink cargo traffic via Piraeus to

influence Greek policy or European

Council's decision on a China issue

Cyber/data risk:

COSCO port operations give access to local

networks and lead to irregular but

sensitive data leaks of civilian and military

data with broader implications

Substantial

Limited

Very

unlikely

Unlikely

Somewhat

likely

Likely

Very

likely

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

25

tough choice over the legal status of the port. In case COSCO does decide to pull out of Piraeus, the

Greek government will find it difficult to swiftly mobilise another port operator.

EU-level dependency risk

A rough estimate as to the share of Chinese imports into the European market transshipped via the

Port of Piraeus points to a figure between 10% and 15%.

13

Given that in 2022 the worth of Chinese

exports to the EU amounted to some EUR 620bn, Piraeus could potentially account for the entry of

Chinese goods worth between EUR 62bn and EUR 93bn into the EU market. However, the one above is

a highly arbitrary analysis, for the reasons set out below.

The Greek market accounts for only a small share of all the Chinese goods delivered at the Port of

Piraeus. Most containers are transshipped to other countries and are unsealed at the final destination.

Therefore, credible data on the nature, worth and strategic importance of Chinese imports via Piraeus

takes time to come by.

In addition, the railway transport corridor from Piraeus to Budapest, which is part of the core TEN-T

(priority axis No22), still absorbs small amounts of containers at this stage – less than 200,000 TEUs in

2021.

14

While COSCO motherships arrive at Piraeus, goods are then transshipped to other

Mediterranean and Black Sea ports on smaller cargo vessels, known as ‘feeders’. Some of these ports

may be in EU Member States, such as Cyprus, Italy, Malta, France, Spain, Portugal, Bulgaria and

Romania. North African states also claim a considerable share of the cargo traffic via Piraeus. As many

goods transshipped via Piraeus go to North Africa rather than to Europe, the role of the Piraeus port in

the overall European supply chain may be more limited than generally assumed.

Furthermore, Greece has yet to adopt an FDI screening mechanism. The Greek government has

prioritised FDI attraction. Although Regulation 2019/452

came into force in October 2020, a year later,

the Greek parliament passed Law 4864/2021 on Strategic Investments, which moves in the opposite

direction.

The Greek government is extremely reluctant to consider changing the status of the Piraeus port. Even

in the case of a major international crisis and a collapse of relations between the EU and China, Greece

is unlikely to challenge the 2016 agreement with COSCO, as amended in 2021.

A complete breakdown of trade through COSCO, arising from an immediate suspension of the

operation of the Chinese forwarder in European ports, including Piraeus, is unlikely. Given the

headwinds that China’s economy is currently facing, Beijing would have to consider the risk of losing –

even if temporarily – Piraeus as a logistics hub and entry point to markets in the EU and the broader

Southeast Europe-MENA region. Chinese producers affected by this development would find it difficult

to divert their exports to other parts of the world swiftly. However, the impact would be severe, given

the EU’s dependence on Chinese imports transported by sea, including via Piraeus. The

Port of Piraeus

is part of the core TEN-T as major hub in the Eastern Mediterranean region (for highways, railways and

transshipment), disruptions in Piraeus therefore would have direct spillovers to other connected hubs

in the EU (i.e., the Helsinki-Valletta corridor and the Hamburg/Rostock-Burgas/TR Border/Piraeus -

Lefkosia corridor).

The imposition of partial countersanctions by China, for example restrictions on essential exports to

the EU, is more likely. Partial Chinese countersanctions, such as restrictions on specific exports to the

EU, could include rare earths (which is already the case with gallium and germanium), batteries for

13

Interviews with representatives of the business community in Piraeus, 26 July 2023.

14

Interview with PPA chairman Yu Zenggang, 27 May 2022.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

26

electric vehicles, solar panels, etc. Piraeus would be a relatively small, but not insignificant, entry point

in the overall European supply chain.

Coercion/influence risk

Greece is one of the most China-friendly EU Member States and, like many other European

governments, wishes to avoid a head-on clash with Beijing. While the current government is unlikely

to repeat the goodwill gestures made to Beijing by its predecessor in 2015-2019, Athens carefully

avoids stepping on China’s toes on ‘sensitive’ political issues, such as the status of Xinjiang, Tibet and

Taiwan, and consistently abstains on related UN resolutions. Greece has neither commented on China’s

coercion against Lithuania

15

nor criticised Beijing’s ‘neutral’ stance towards Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

However, Greece has not opposed EU sanctions against China on human rights related issues and

cyber-attacks.

In the event of a major international crisis, Beijing would seek to split the EU through ‘China-friendly’

voices, including Greece. Coercion cannot be precluded, but it is likely to be discreet rather than

undisguised. China may consider a range of possible responses, such as: exerting pressure on the Greek

government by threatening to freeze bilateral relations; restricting strategic exports to Greece, without

announcing an official embargo; quietly diverting traffic to other ports in the Mediterranean; and

explicitly informing Greek authorities that, if they support EU decisions, COSCO will halt investments

and will redirect flows to other destinations.

Although the complete shutdown of the Piraeus port as a consequence of economic coercion is

deemed highly unlikely, the port could be used by Beijing as a lever, given that COSCO’s investment is

a significant part of the Greek government’s FDI attraction strategy. However, Piraeus is a major

Chinese asset in the Mediterranean, and Beijing would not like to jeopardise its status through extreme

political pressure on Athens.

Cybersecurity/data risk

The Hellenic Port Community System (HPCS) dispute illustrates COSCO’s interest in data collection and

management, which could have economic and security implications. COSCO certainly has the

opportunities and resources to create an infrastructure that would allow it to ‘eavesdrop’ on Greek state

and military services in the broader area of Piraeus. The impact could be severe for state, international

and military infrastructure (Ministry of Shipping, Coast Guard, Greek Navy, visiting NATO military

vessels and global telecoms networks). PPA has granted nine offices and exterior space totalling a

surface of 1,100 sq metres to the Special Forces (KEA) of the Greek Coast Guard. COSCO has borne the

cost of the development and renovation of these sites. It is unclear to what extent the facilities are

equipped with the requisite safeguards in case Chinese listening equipment is installed in the area.

The ‘symbiosis’ of COSCO and several Greek state institutions in the same area (Ministry of Shipping,

Coast Guard and the Salamina naval base) is highly problematic. It is noted that the Greek naval base

at Salamina is less than five nautical miles away from Piraeus, i.e. within a range that allows – in theory,

at least – for the use of listening devices. There are (unconfirmed) reports of a secret telecoms unit at

PCT, with access granted to very few Chinese representatives.

A critical factor is the low level of awareness and understanding of cyber threats among Greek public

authorities. Notably, in early 2020 COSCO presented its HPCS platform to the Greek Ministry of Digital

Governance, which initially accepted it

. However, the local business community in Piraeus reacted

vehemently and only then did the Greek government realise the potential threat.

15

In 2021, Lithuania became the sixth European country to face an episode of Chinese economic coercion. The episode followed the

opening of a “Taiwanese Representative Office” in Vilnius in November 2021. https://merics.org/en/executive-memo/dealing-chinas-

economic-coercion-case-lithuania-and-insights-east-asia-and-australia

Chinese Investments in European Maritime Infrastructures

27

Greece has a National Cybersecurity Strategy, published in 2018 and updated in 2020. It focuses on

security policies for ICT systems in the public sector, and co-operation with the competent national

authorities, The European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA), etc. It is likely that this strategy

requires an update, or a specific chapter on potential cyber threats related to COSCO’s presence in

Piraeus.

Piraeus is often visited by military vessels from other NATO members, including the US. For instance,

the aircraft carrier USS Gerald R. Ford visited Piraeus

in late July 2023, although it did not enter the port.

It is the US navy's most advanced aircraft carrier, with 23 new technologies that operate with a 20%

smaller crew than Nimitz-class carriers. Furthermore, there are indications that calls by US military

vessels will be more frequent in the future. It is reasonable to assume that Chinese intelligence services

will be interested in collecting data about US advanced military technologies.

Hard security risk

The Chinese navy occasionally visits ports throughout the region, usually after concluding counter-

piracy patrols in the Gulf of Aden and before returning to China. Chinese warships have visited Piraeus

several times since 2002, most recently in October 2017, when the Greek and Chinese navies held one-

day joint drills. Despite the symbolic nature of this exercise, port calls of Chinese warships feed into the

debate on the potential dual use of COSCO’s investment project. Concerns over possible military use

are not entirely unwarranted, despite assurances by Greek authorities that they would never allow this.

In June 2015 the Chinese government announced that all civilian shipbuilders had to ensure that their

new vessels were suitable for military use in emergencies. This new strategy is designed to enable China

to convert the considerable potential of its civilian fleet into military strength

to protect strategic lines

of communication and maritime support capabilities. In other words, all new COSCO container ships

docking in the port of Piraeus will – in theory, at least – be capable of being converted into military

vessels at short notice and used in military operations.

As argued elsewhere, Piraeus port is seen by Chinese authorities as a valuable asset. They would be

unwilling to sacrifice it by turning it into a military facility, as this would justify the suspension of

diplomatic relations between Greece and China. Above all, Greece’s commitment to NATO, in

conjunction with the defence agreements between Greece and the US on the one hand, and Greece

and France on the other, render Chinese military activism in the Mediterranean virtually impossible.

In case of unrest in North Africa and a repeat of the Libya-2011 crisis, China will be called upon to

protect its assets and evacuate its citizens. Yet, it is unlikely that Greek authorities, as well as NATO

partners, would agree to the Piraeus port being used by China’s navy in such a rescue operation. In

addition, China may have other options in the Mediterranean, such as existing facilities or terminals

under construction in Egypt (at Alexandria, Port-Said and El-Dekheila) or Algeria (Cherchell).

Last but not least, in a major international crisis involving China, the main battle theatre is expected to

be in the Indo-Pacific, not the Mediterranean Sea. In such a scenario, the US 6th Fleet would probably

block the Suez Canal and thus prevent Chinese military and merchant ships from entering or leaving

the Mediterranean.

IPOL | Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies

28

2.3. Hamburg, Germany

Background