Reading Apprenticeship is an approach to reading instruction that helps students develop

the knowledge, strategies, and dispositions they need to become more powerful readers. It

is at heart a partnership of expertise, drawing on what teachers know and do as discipline-

based readers, and on adolescents’ and young adults’ unique and often underestimated

strengths as learners. Reading Apprenticeship helps students become better readers by

R (!!#(!5-./(.-5#(5'),5,#(!A ),5,,.#)(5-51&&5-5 ),5-/$.5,5&,(#(!

and self-challenge;

R %#(!5."5.",]-5#-#*&#(7-5,#(!5*,)---5(5%()1&!50#-#&5.)

students;

R %#(!5-./(.-]5,#(!5*,)---65').#0.#)(-65-.,.!#-65%()1&!65(5/(,-

standings visible to the teacher and to one another;

R &*#(!5-./(.-5!#(5#(-#!".5#(.)5."#,5)1(5,#(!5*,)---:5(

R &*#(!5."'50&)*55,*,.)#,5) 5*,)&'7-)&0#(!5-.,.!#-5 ),5)0,)'#(!5)-

stacles and deepening comprehension of texts from various academic disciplines.

The Reading Apprenticeship

®

Framework

Reading Apprenticeship

Strategic Literacy Initiative

© 2017 WestEd

1

Reading Apprenticeship Framework

In other words, in a Reading Apprenticeship classroom, the curriculum expands to

include how we read and why we read in the ways we do, as well as what we read in

subject area classes.

Reading Apprenticeship instructional routines and approaches are based on a framework

that describes classroom life in terms of interacting dimensions that support reading

development:

Social: The social dimension draws on learners’ interests in peer interaction as well as

larger social, political, economic, and cultural issues. Reading Apprenticeship creates a

safe environment for students to share their confusion and difficulties with texts, and to

,)!(#45."#,5#0,-5*,-*.#0-5(5%()1&!85

Personal: This dimension draws on strategic skills used by students in out-of-school

settings, their interest in exploring new aspects of their own identities and self-awareness

as readers, their purposes for reading, and their goals for reading improvement.

Cognitive: The cognitive dimension develops readers’ mental processes, including

their repertoire of specific comprehension and problem-solving strategies. The work of

generating cognitive strategies that support reading comprehension is carried out through

shared classroom inquiry.

Knowledge-Building: This dimension includes identifying and expanding the knowledge

readers bring to a text and further developing it through personal and social interaction

with that text. Students build knowledge about language and word construction, genre

(5.2.5-.,/./,65(5."5#-)/,-5*,.#-5-*# #5.)55#-#*&#(A#(5#.#)(5.)5."5

concepts and content embedded in the text.

These dimensions are woven into subject area teaching through Metacognitive

Conversations

A)(0,-.#)(-5)/.5."5."#(%#(!5*,)---5-./(.-5(5.",-5(!!5

in as they read. Extensive Reading—increased opportunities for students to practice

,#(!5#(5'),5-%#&& /&513-A#-5."5(--,35)(.2.5 ),5."#-5 ,'1),%5.)5-/8

Reading Apprenticeship

Strategic Literacy Initiative

© 2017 WestEd

9

2

Reading Apprenticeship Framework

1

Reading Apprenticeship is an approach to reading instruction that helps students develop the

knowledge, strategies, and dispositions they need to become more powerful readers. It is at heart

a partnership of expertise, drawing on what teachers know and do as discipline-based readers,

and on adolescents’ and young adults’ unique and often underestimated strengths as learners.

Reading Apprenticeship helps students become better readers by

● Engaging students in more reading--for recreation as well as for subject area learning and

self-challenge;

● Making the teacher’s discipline-based reading processes and knowledge visible to

students;

● Making students’ reading processes, motivations, strategies, knowledge, and

understandings visible to the teacher and to one another;

● Helping student gain insights into their own reading processes; and

● Helping them develop a repertoire of problem-solving strategies for overcoming

obstacles and deepening comprehension of texts from various academic disciplines.

In other words, in a Reading Apprenticeship classroom, the curriculum expands to

include how

we read and why

we read in the ways we do, as well as what

we read in

subject area classes.

Reading Apprenticeship instructional routines and approaches are based on a framework

that describes classroom life in terms of interacting dimensions that support reading

development:

Social: The social dimension draws on learners’ interests in peer interaction as well as

larger social, political, economic, and cultural issues. Reading Apprenticeship creates a

safe environment for students to share their confusion and difficulties with texts, and to

recognize their diverse perspectives and knowledge.

● Creating safety

● Investigating the relationship between literacy and power

● Investigating the relationship between literacy and social identity

● Investigating the relationship between literacy and status

● Sharing text talk

1

Adapted from Schoenbach, R., Greenleaf, C., & Murphy, L. (2012). Reading for understanding, 2nd ed.

San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass, Inc.

3

● Sharing reading processes, problems, and solutions

● Noticing and appropriating others’ ways of reading

● Noticing and appreciating cultural resources others bring to texts

Personal: This dimension draws on strategic skills used by students in out-of-school

settings, their interest in exploring new aspects of their own identities and self-awareness

as readers, their purposes for reading, and their goals for reading improvement.

● Developing reader identity

● Identifying out-of-school cultural resources that can support in-school literacy practices

● Developing metacognition

● Addressing affective dimensions of literacy learning that result from cultural mismatch or

pervasive negative stereotypes

● Finding or creating identification in de-raced texts

● Developing reader fluency and stamina

● Developing reader confidence and range

Cognitive: The cognitive dimension develops readers’ mental processes, including

their repertoire of specific comprehension and problem-solving strategies. The work of

generating cognitive strategies that support reading comprehension is carried out

through shared classroom inquiry.

● Getting the big picture

● Breaking it down

● Monitoring comprehension

● Monitoring affective responses

● Identifying life-based problem-solving strategies that can be applied to reading

● Using problem-solving strategies to assist and restore comprehension

● Setting reading purposes and adjusting reading processes

Knowledge-Building: This dimension includes identifying and expanding the knowledge

readers bring to a text and further developing it through personal and social interaction with that

text. Students build knowledge about language and word construction, genre and text structure,

embedded in the text.

● Surfacing, building, and refining schema

● Identifying relevant cultural funds of knowledge

● Building knowledge of content and words

4

● Building knowledge of texts

● Building knowledge of language

● Building knowledge of disciplinary discourse and practices

These dimensions are woven into subject area teaching through Metacognitive

Conversations--conversations about the thinking processes students and teachers engage in

as they read. Extensive Reading—increased opportunities for students to practice reading in

more skills ways--is the necessary context for this framework to succeed.

5

Setting the Social and Personal Foundations for Inquiry

75

Personal Reading

History Protocol

Individually and then together, team members reflect on high and low moments in their reading histories

and the implications for their work inquiring into their own reading and the reading of their students.

PURPOSE

The group understands that the Personal Reading History routine is an opportunity to reflect on

how people develop reader identities and what hinders or helps in that development. By sharing

their reader histories, team members will better understand the beliefs and attitudes about reading

development they bring to their work together. The activity will also help team members rehearse what

it might be like to bring the Personal Reading History into their classrooms.

INDIVIDUAL WRITING

Provide about ten minutes for team members to write individual responses to prompts about key

moments or events in their development as readers:

• What reading experiences stand out for you? High points? Low points?

• Were there times when your reading experience or the materials you were reading made you feel

like an insider? Like an outsider?

• What supported your literacy development? What discouraged it?

PARTNER SHARING

Explain that partners and then the whole group will share highlights from their journey to becoming

adult readers and subject area teachers. Allow six minutes for partners to share. Provide these guidelines:

• Take turns describing some highlights of your reading histories. Let one person speak without inter-

ruption, then discuss. Reverse roles after three minutes.

• Discuss commonalities and surprises in your histories.

• What were some similarities in your barriers and supports?

• What were some surprises?

GROUP DISCUSSION

The whole group debriefs these reflective partnerships. As in debriefing the Personal Reading History

in classrooms, it is important to make sure there is space made for participants to talk about reading

barriers and not to assume that reading has been easy and supported for everyone on the team.

• What ideas do you have about the impact of reading experiences in people’s lives?

• What ideas do you have about how reflecting and sharing our Personal Reading Histories may

impact our work as a team?

• How might teachers and students benefit from doing Personal Reading Histories in class?

*See also the discussion and protocol for classroom investigation of Personal Reading History in Chapter Three of Reading for Understanding.

TEAM TOOL 4.2

6

Reproduced with permission of the

copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

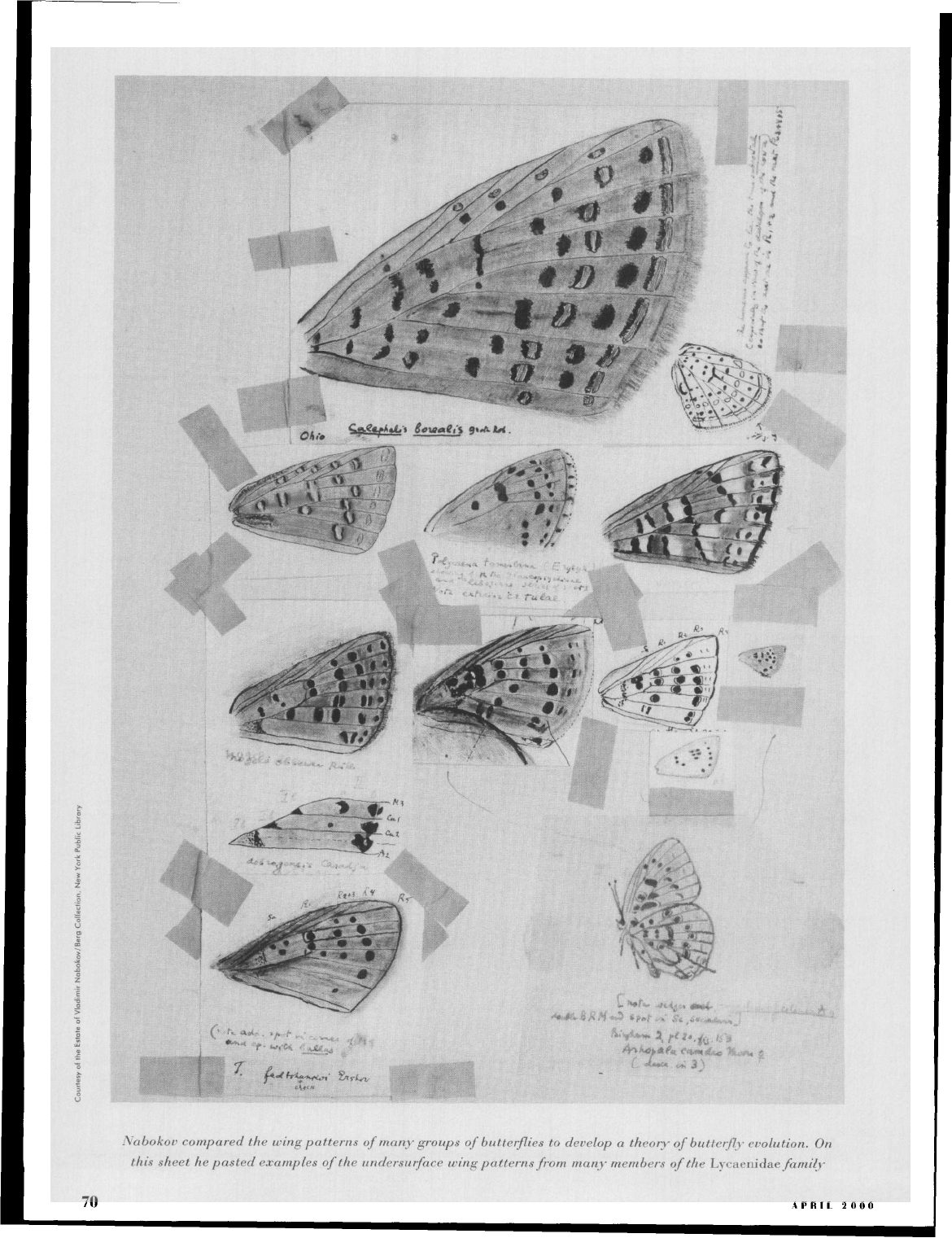

Father's butterflies

Nabokov, Vladimir

The Atlantic Monthly; Apr 2000; 285, 4; ABI/INFORM Collection

pg. 59

7

Reproduced with permission of the

copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

8

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

9

9

Reproduced with permission of the copyright owner. Further reproduction prohibited without permission.

10

Capturing the Reading Process Notetaker

Reading Process Analysis

Individual Reading

Read silently as you would when you want to understand something. Use any strategies

you commonly use to make sense of text. (Pens and sticky notes are in the table boxes.)

Individual Think-Write

Take a few minutes to make some notes about the processes you used to make sense of

this text.

Even if you weren’t explicitly aware of them while you were reading, what strategies or

approaches did you use to engage with or make sense of the text? Where was the text

unclear? What did you do to make sense of it at that point? What problems remain,

ifany?

11

Our Reading Strategies List

The strategies our group used to make sense of the text:

Notes for getting started in the classroom:

12

106

Reading for Understanding

English teacher Doug Green

3

reverted to literature instruction instead of think-

ing aloud—more than he is happy remembering:

I found myself falling into explaining the short story to them rather than

talking about my thinking as I read the short story. It was really hard for me

to discipline myself to do that because one of the thinking strategies is mak-

ing connections to other things. And as soon as I start making connections

to other things, I lead myself very quickly into explaining the short story

instead of talking about my thinking techniques. That was hard to resist.

The idea of modeling a Think Aloud for her adult GED students gave

technical college instructor Michele Lesmeister the jitters. As she explains in

BOX 4.7

Using a Metacognitive Bookmark

PURPOSE

When teachers fi rst model metacognitive

conversation with a Think Aloud, many give students

a bookmark for keeping track of the common kinds

of thinking processes the teacher will be

demonstrating.

Students can use this same bookmark as a scaff old

for their own metacognitive conversations when

practicing with a partner.

As a scaff old, its use should fade as students become

more comfortable with metacognitive conversation

routines.

PROCEDURE

• Give each student a copy of the bookmark and

briefl y review students’ understanding of the various

categories and examples.

• Explain that as you Think Aloud, you will model

many of these. Ask students to listen for examples.

• Think Aloud, modeling metacognitive conversation.

• Invite students to describe some of the thinking

processes you used.

Let students know that they can use the bookmark

whenever they practice metacognitive conversation on

their own and with classmates.

Note: The bookmark is a sample only. Please adapt and revise it according to your subject area and student needs.

Sample Metacognive Bookmark

Predicng

I predict . . .

In the next part I think . . .

I think this is . . .

Visualizing

I picture. . .

I can see . . .

Quesoning

A queson I have is . . .

I wonder about . . .

Could this mean . . .

Making connecons

This is like . . .

This reminds me of . . .

Idenfying a problem

I got confused when . . .

I’m not sure of . . .

I didn’t expect . . .

Using fix-ups

I’ll reread this part . . .

I’ll read on and check back . . .

Summarizing

The big idea is. . .

I think the point is. . .

So what it’s saying is. . .

13

Health-Related

Variables

and

Academic

Performance

Among

First-Year

College

Students:

Implications

for

Sleep

and

Other

Behaviors

Mickey

T.

Trockel,

MS;

Michael

D.

Barnes,

PhD;

Dennis

L.

Egget,

PhD

Abstract.

The

authors analyzed the

effect

of

several

health

behaviors

and

health-related

variables

on

grade

point

averages

of

a

random

sample

of

200

students

living

in

on-campus

residenice

halls

at

a

large

private

university.

The

set

of

variables

included

exer-

cise,

eating,

and

sleep

habits;

mood

states;

perceived

stress;

time

management;

social

support;

spiritual or

religious

habits;

niunber

of

hours

worked

per

week;

gender; and

age.

Of

all the

variables

considered,

sleep

habits,

particuIlarly

wake-up

times,

accounted

for

the

largest

amnount

of

variance

in

grade

point

averages.

Later

wake-

up

times

were

associated

with

lower

average

grades.

Variables

associated

with

the

Ist-year

students'

higher

grade

point

averages

were

strength

training

and

study

of

spiritually oriented material.

The

number

of

paid

or

volunteer hours worked

per

week

was

asso-

ciated with

lower average

grades.

Key

Words:

academic performance, college

students,

grade

point

average,

health-related behaviors,

sleep

Improved

academic

performance

is

an

appropriate goal

for

college

health promotion

personnel,

just

as

improved

job

performance

is

a

desired outcome for

worksite

health

promotion professionals. A

common

measure

of

academic

performance

is

grade

point

average

(GPA),

and

determining

the

factors

that most

affect

it

is

important

to universities.

Good

grtdes

in

college

are

highly

related

to career success.t

Health behaviors potentially

affecting college

student

GPA

include

a

wide

range

of

actions

and

habits:

exercise.

sleep,

and

nutritional

habits;

development

and

use

of

social

support

systems;

time

and stress

management

techniques.

2

Health-related variables

in

addition to

other

physical,

emo-

tional, social,

and

spiritual health

itidicators

potentially

Mickey

T:

Trockel is

a

dloctoral

candidcate

in

the DJepartment

of

Communi7zty

Healtth,

University

of

Illinois.

Chamwpaign;

Michael

D.

Barnes

is

an

associate

professor

in

the

Department

of

Health

Sciences

at

Brigham

Youing

University

in

Provo,

Utah,

where

Dennis

L.

Egget

is

director

of

the

Statistical

Research

Center.

VOL

49,

NOVEMBER

2000

affect

college

students'

academic

perfornance.

Clearly,

it

is

not

possible

for one

study to

consider the entire range

of

health-related

variables that

are

potential

influences on

col-

lege

students'

GPAs.

In

this

study,

we analyzed the

effects

of

several

health-

r

elated variables

on

1st-year

college

students'

GPAs.

Although

several

studies

have

identified the influence

of

many

health-related

factors

on

academic

performance,

the

results

have

often

been inconsistent.

Furthermore,

college-

specific

information

regarding

academic

performance

and

its

relationship

to

health-related behaviors

is

rare.

3

Such

information

has

implications

for

developing

programs

and

services,

helping

colleges and universities retain

students,

improve students'

academic

performance,

and

reduce

the

resource

burden for

student

support

servicesi.

3 4

Previous

Studies

Exercise

A

few

researchers

have

evaluated the effect

of

exercise

on

university

students' academic

performance.

Turbow,

5

in

a

study involving

891

upperclassmen

and graduate

students,

found

students who

exercised

7

or

more

hours

per

week

obtained

significantly

lower grades than students

who

exer-

cised

6

or

fewer

hours

weekly

or

not

at

all.

However,

a

study

involving

710

students

at

California

State University.

Fres-

no,

6

was

unable

to show

a

significant

relationship between

academnic

achievement and

exercise.

The reasons

for

these

disparate

results

are

not

apparent.

Sleep

Habits

Reports

in the

literature implicate

a

negative

effect of

sleep

deprivation

on

college students' cognitive perfor-

mance.

7

One observer found

poorer

academic

performance

among university

students

whose

weekend sleeping periods

were

significantly

delayed compared with

weeknight

sleep-

125

14

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

TITLE: Health-related variables and academic performance among

first-year college students: implications for sleep and

other behaviors

SOURCE: Journal of American College Health 49 no3 N 2000

WN: 0030602584004

The magazine publisher is the copyright holder of this article and it

is reproduced with permission. Further reproduction of this article in

violation of the copyright is prohibited.

Copyright 1982-2001 The H.W. Wilson Company. All rights reserved.

15

Evidence

I saw, heard, read...

Interpretation

I wondered, made a connection, thought…

16

134

Leading for Literacy

• Team Tool 6.4, Identifying Routines and Scaffolds Note Taker, then invites

teachers to review Reading for Understanding with a stack of sticky notes at

hand, tagging specific routines and scaffolds that could support their begin-

ning instructional goals.

• With those ideas from Reading for Understanding in mind, teachers fill in

a matrix that relates goals, content, texts, activities, the Framework, and

A Progression for Building

Metacognition in Shared

Class Reading

In this model sequence of metacognitive reading experiences that build students’ reading

independence, the first three activities occur once, and the others recur in increasingly refined

or increasingly expansive iterations.

Student Reading Survey

STUDENT GROWTH OF INDEPENDENCE OVER TIME

ONGOING SELF-ASSESSMENT AND REFLECTION

Personal Reading History

Capture the Reading Process

Create Reading Strategies List

Practice Think Aloud

Revise and update Reading Strategies List

Integrate disciplinary and other new strategies

into Think Aloud

Practice Talking to the Text

Revise and update Reading Strategies List

Integrate disciplinary and other new

strategies into Talking to the text

Practice Double-Entry and

other Metacognitive Logs

Use Think Aloud,

Talking to the Text,

and Metacognitive Logs

to practice new strategies

TEAM TOOL 6.3

17