Policy report

December 2015

Zero-hours and

short-hours

contracts

in the UK: Employer and

employee perspectives

The CIPD is the professional body for HR and people

development. The not-for-profit organisation champions

better work and working lives and has been setting the

benchmark for excellence in people and organisation

development for more than 100 years. It has 140,000

members across the world, provides thought leadership

through independent research on the world of work, and

oers professional training and accreditation for those

working in HR and learning and development.

1 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

1 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Zero-hours and short-hours contracts

in the UK: Employer and employee

perspectives

Policy report

Acknowledgements 1

Foreword 2

Glossary 3

Executive summary 4

Introduction 10

Employer perspectives 13

Employee perspectives 26

Conclusions 37

References 41

Endnotes 42

Contents

Acknowledgements

The CIPD is grateful to David Freeman and Mark Chandler at the Office for National Statistics for

providing unpublished analyses of the Labour Force Survey.

The Labour Market Outlook and Employee Outlook surveys used in this report were administered by

YouGov and the CIPD is grateful to Ian Neale and Laura Piggott at YouGov for advice on the use of the

survey data in this report. The CIPD also thanks all the respondents who gave their time to contribute

to these surveys.

Any errors that remain are entirely the CIPD’s responsibility.

2 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 3 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Zero-hours contracts remain

controversial, but the number

of people on them is increasing

and they look set to become a

permanent feature of the UK

labour market.

The CIPD has made a leading

contribution to understanding

of zero-hours contracts and our

research has been quoted by

government, employers and unions

– both supporters and opponents

of zero-hours contracts.

Zero-hours contracts have

sometimes, it seems, been singled

out as an especially unfair form

of employment. In our view, this

is unjustified. Our research shows

that zero-hours contracts appear

to work well for many of those

on them. But they are not for

everybody and that’s why zero-

hours contract workers need to

understand their employment

rights as well as how these

contracts are likely to work in

practice. Zero-hours contracts

work best when there’s an element

of give and take, a recognition that

flexibility works both ways. A small

minority of employers using them

don’t seem to recognise this, but

there are many ‘permanent’ jobs

where the actions of employers

can make them anything but

secure. There may be too much

emphasis at times on the precise

terms of the employment contract

with not enough attention given to

the spirit in which the employment

relationship is conducted.

We have updated our estimate

of the number of zero-hours

contracts from about 1 million

in 2013 to about 1.3 million in

the spring and summer of 2015.

Otherwise, this research has

produced very similar results. On

average, employees on zero-hours

contracts are as satisfied with

their jobs as other employees and

report similar levels of well-being.

While they may be less likely to

feel involved at work and see

fewer opportunities to develop and

improve their skills, they are also

less likely to feel overloaded and

under excessive pressure.

This report also presents

comparable data for those

employed on short-hours

contracts, defined here as jobs

that guarantee up to eight

hours’ work a week. This is a

smaller group of about 400,000

employees who are qualitatively

different from zero-hours contract

employees in terms of their

working patterns and working

hours. They are also more satisfied

with their situation than any other

group of workers we identified in

our Employee Outlook survey.

Our message to employers –

including our members – is to

think carefully about whether

or not these types of contracts

are suitable for your business.

This involves broader issues than

whether or not they help you

match demand to supply. For

example, do they help strengthen

your working culture and your

employer brand?

Our message to employees on

these contracts, and those thinking

about taking one, is to find out

exactly what you are being asked

to agree to, what your rights and

responsibilities are and how these

types of work are used in practice.

Ask questions such as whether

there is a minimum notice period

when work is withdrawn and, if this

does occur, whether you would

be compensated for any costs

incurred.

Our message to government

and the policy community is

that heavy-handed changes to

the law, such as attempts to

abolish zero-hours contracts,

are likely to be both ineffective

and counterproductive. But the

research does raise issues about

employment status, access to

employment rights and the

treatment of zero-hours contract

employees. Modest, targeted

changes to current legislation

may be an option worth further

discussion, but the best way to

improve the working lives of

people on zero-hours contracts

is to help employers develop

working practices that are both

flexible and fair.

Peter Cheese

CIPD Chief Executive

Foreword

3 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Discussions of the advantages and disadvantages of different forms of work sometimes lack precision on

terminology and definitions. Below are explanations of the terminology used in this report (any deviations

from these are highlighted in the report). These do not necessarily match corresponding legal concepts.

Employee An employee is anyone in work who does not regard themselves

as self-employed. Both CIPD and ONS surveys do not identify the

‘worker’ category that appears in employment law.

Full-time employee Any employee who says their work is full-time or who usually works

30 or more hours each week.

Part-time employee Any employee who says their work is part-time or who usually works

for less than 30 hours each week.

Short-hours contracts Employment where the employer guarantees a small minimum

number of hours each week and where the employer has the option

of offering additional hours (which the employee may have the option

of being able to refuse). This report uses eight hours a week as the

upper limit on what constitutes a ‘small’ number of hours.

Temporary employment Employment which is not permanent (as defined by the employee).

Zero-hours contract There is no generally accepted definition of a zero-hours contract.

CIPD guidance uses the following definition: ‘an agreement between

two parties that one may be asked to perform work for the other but

there is no set minimum number of hours. The contract will provide

what pay the individual will get if he or she does work and will deal

with the circumstances in which work may be offered (and, possibly,

turned down)’ (CIPD 2013c).

New government guidance describes a zero-hours contract as ‘one

in which the employer does not guarantee the individual any hours of

work. The employer offers the individual work when it arises, and the

individual can either accept the work offered, or decide not to take up

the offer of work on that occasion’ (BIS 2015).

Although the lack of any guaranteed minimum hours of work is

common to both definitions, the government definition suggests

that individuals are able to decline offers of work whereas the CIPD

definition recognises this may not always be the case.

Glossary

4 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 5 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

This report updates and extends

the analysis of zero-hours contract

work presented in the previous

CIPD report Zero-hours Contracts:

Myth and reality.

In addition, it presents data on

short-hours contract working. As

with zero-hours contracts, there is

no universally accepted definition

of a short-hours contract. This

report uses a guaranteed minimum

of eight hours a week as the upper

limit for a short-hours contract.

The report is based upon

analysis of survey data from both

employers and employees.

The employer perspective is

provided by the CIPD’s quarterly

Labour Market Outlook (LMO), a

representative sample survey of

all employers in the UK with two

or more employees. Questions

on zero-hours and short-hours

contracts were included in the

surveys conducted in the spring

and summer of 2015, which

generated responses from 1,013

employers and 931 employers

respectively.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS)

collects data on employees with

zero-hours contracts. This has been

supplemented with data from the

CIPD’s summer 2015 Employee

Outlook (EO) survey, which

generated responses from 2,572

employees.

Zero-hours contracts

Employer perspective

According to the LMO surveys

conducted in spring and summer

2015, about a quarter of employers

use zero-hours contracts, little

changed from the 2013 estimate

of 23%.

Employers generally use zero-

hours contracts for a relatively

small proportion of the workforce.

Over half of employers use them

for less than 20% of the workforce

– with the mean percentage

covered being 19.7%.

A best estimate for the number of

zero-hours contract employees at

spring/summer 2015 is 1.3 million,

which is an increase from the

previous estimate of 1 million in

2013.

Employers in the public and

voluntary sectors are more likely

to use zero-hours contracts than

private sector employers. Zero-

hours contracts are most often

used by employers in hotels,

accommodation and food, health

and social work (which includes

social care), education and the

voluntary sector.

Large organisations are much more

likely than small organisations to

use zero-hours contracts.

Employers use zero-hours contract

workers in a variety of roles. The

jobs most commonly mentioned

by employers are in administrative

and support roles, care work,

cleaning and various hospitality-

related functions, although some

more skilled jobs (nursing, IT,

teaching) are also mentioned quite

regularly.

The mean number of hours

usually worked by zero-hours

contract workers is 19.4 hours a

week. Although 70% of employers

typically employ them for 20

hours or less each week, 20% of

employers typically employ them

for 30 or more hours each week.

Over two-fifths of employers

(44%) say that working hours are

driven largely by the employer,

with 15% emphasising the role

of the individual. The remaining

employers focus on the variability

and unpredictability of working

time.

The most common reasons for

using zero-hours contracts are to

manage fluctuations in demand

(mentioned by 66% of employers),

provide flexibility for the individual

(51%) and provide cover for

absences (48%). Reducing costs

is a specific objective for 21% of

employers.

Almost half (47%) of employers

using zero-hours contracts see

them as a long-term feature of

their workforce strategy, likely to

still be in use in four or more years’

time.

Most employers of zero-hours

contract staff (67%) classify them

as employees, with 19% classifying

them as workers, 5% as self-

employed, 6% not classifying their

status and 1% unaware – very

similar responses to those given in

2013.

Over four-fifths (81%) of employers

provide zero-hours contract

workers with a written contract,

although 8% do not provide a

contract and 8% say it varies,

with 3% unsure because workers

are supplied by a recruitment

Executive summary

5 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

‘More than half of

employers (58%)

give zero-hours

contract workers

the contractual

freedom to turn

work down and

say they honour

this in practice.’

agency. Where a written contract is

provided, 86% of these employers

say it records employment status.

More than half of employers (58%)

give zero-hours contract workers

the contractual freedom to turn

work down and say they honour

this in practice. However, a fifth of

employers (21%) say that contracts

give workers the right to turn work

down when, in practice, they are

always or sometimes expected to

accept all work offered. A further

14% say their zero-hours contracts

do not allow employees to turn

work down.

Two-thirds (66%) of employers

have some form of policy or

practice on notice of termination,

compared with 55% in 2013. Less

than half of employers (45%) say

they have policies or practices

when it comes to cancelling a shift.

Almost two-thirds (63%) of

employers pay zero-hours contract

employees about the same hourly

rate as employees on a permanent

contract doing the same job. Some

employers (16%) pay a higher rate

and others (9%) pay a lower rate.

Over four-fifths (82%) of employers

using zero-hours contract workers

say they are eligible for company

training and development, with just

13% saying this is not the case.

Employers are most likely to say

people on zero-hours contracts are

entitled to annual paid leave (61%),

the right to receive a statement

of written terms and conditions

(59%) and the statutory minimum

notice period (57%). Reported

entitlements have generally little

changed since 2013, although

there has been a noticeable

increase in the proportion of

employers saying zero-hours

contract workers are entitled to

pension auto-enrolment, up from

38% in 2013 to 48% in 2015.

Only 6% of employers using

zero-hours contract workers even

occasionally prohibit them from

working for another company. This

suggests that the prohibition of

exclusivity clauses is unlikely to

affect many employers.

Employee perceptions

According to the LFS, the number

of people on zero-hours contracts

has almost tripled in less than

three years, from 252,000 in

October–December 2012 to

744,000 by April–June 2015 (46%

men, 54% women). Much of this

reported increase may be due to

greater public awareness of zero-

hours contracts.

Exactly one-quarter of zero-hours

contract employees are students

still in full-time education, which

helps to explain why a third of

zero-hours contract employees

are aged under 25. One-fifth of

zero-hours contract employees are

aged 25–34, another fifth are aged

35–49, and just under a quarter are

aged 50 or over.

The mean number of hours usually

worked each week by zero-hours

contract employees in April–June

2015 is 25.1 hours. The majority

(59%) of zero-hours contract

employees do not want to work

more hours, compared with 88% of

all those in employment.

According to the summer 2015

EO, the mean number of hours

usually worked each week by zero-

hours contract employees is 23.9

hours, almost identical to the 2013

estimate of 23.7 hours. Just over

half (52%) of zero-hours contract

employees usually work for less

than 25 hours a week, although

one-seventh (14%) work for longer

than 40 hours each week.

Almost three-fifths (59%) of zero-

hours contract employees describe

themselves as part-time workers.

6 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 7 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

The vast majority (88%) of these

say it is their choice to work part-

time. Nevertheless, 22% of these

‘voluntary’ part-time employees

on zero-hours contracts would

like additional hours. The most

common reason for not working

more hours is a perception that

employers are unable to offer more

hours (mentioned by 81% of zero-

hours contract employees wanting

to work more hours).

The proportion of zero-hours

contract employees describing

their job as temporary (rather

than permanent) is 37%. A little

over half (57%) of temporary zero-

hours contract employees say this

is their choice (although a few of

these would prefer a permanent

contract). The vast majority (87%)

of those who say their temporary

status is not their choice would

prefer a permanent contract.

According to the LFS, mean

earnings for zero-hours contract

employees are £8 per hour,

whereas they are £13 per hour

for those not on a zero-hours

contract. Part of the gap can

be explained by compositional

effects: zero-hours contract

work tends to be concentrated

in relatively low-paid industries,

such as accommodation and food.

However, a difference exists in

every broad industry grouping.

According to the summer 2015

EO, 49% of zero-hours contract

employees earn less than £15,000

per year. Nevertheless, there are a

few zero-hours contract employees

with relatively high earnings: 9%

earn £45,000 or more.

The proportion of zero-hours

contract employees who are either

very satisfied or satisfied with their

jobs is 65%, slightly higher than

the proportion for employees as a

whole (63%). However, part-time

zero-hours contract employees

are much less likely to be satisfied

with their jobs if they want to work

more hours.

Just 60% of zero-hours contract

employees say they have a

manager or supervisor or someone

they report to as part of their job,

with a further 17% saying they

sometimes have a manager and

23% having no manager. When

zero-hours contract employees

do have a manager, they are

slightly more likely to be satisfied

with their relationship with them

than other employees. Zero-

hours contract employees are

just as positive about working

relationships with colleagues as

other employees.

Zero-hours contract employees are

more likely to see their work–life

balance in a positive light (62%

strongly agree or agree they have

the right balance) than other

employees (58%).

Whereas 41% of employees feel

under uncomfortable and excessive

pressure at work at least once or

twice a week, the proportion is

just 34% for zero-hours contract

employees. Zero-hours contract

employees with excessive workloads

are as likely as other employees in

that position to feel under pressure

– but they are much less likely to

have an excessive workload.

The (smaller) proportion of zero-

hours contract employees who

do feel under excessive pressure

at work are less likely than

other employees to say there is

support available from managers,

colleagues or anywhere else.

Zero-hours contract employees are

as satisfied with their job role and

the degree of challenge it offers

as other employees. However, they

are slightly less likely to think their

employer gives them opportunities

to learn and grow.

Less than half (43%) of zero-hours

contract employees feel fully or

fairly well informed about what is

going on at work, compared with

56% of all employees. This carries

through into less satisfaction with

the opportunities they have to

feed their views and ideas upwards

within the organisation.

Conclusions

Two-fifths of employers (39%)

think zero-hours contracts will be a

long-term feature of the UK labour

market – in other words, around

for the next four years, if not

longer. A slightly larger proportion

(43%) see them as a short- to

medium-term feature of the labour

market, with 18% unsure.

The proportion of employers

suggesting they might be a

transient form of employment

practice is surprisingly high given

how long some employers have

been using zero-hours contracts.

Although the number of people

employed on zero-hours contracts

has increased since 2013, there is

no evidence of any qualitative shift

in why they are used, how they are

used or in their impact on either

organisations or individuals.

Zero-hours contract employees are

more likely than other employees

to have hours (and earnings) that

vary from week to week – including

the possibility of spells when there

is no work and thus no income from

work. This variability will be a source

of anxiety to some, especially for

those faced with large and regular

financial commitments. It can be

seen in lower job satisfaction among

those who want to work more

hours (a characteristic shared with

other part-time employees wanting

more hours). But other zero-hours

contract employees will regard

uncertainty as an acceptable price

for the freedom to turn down work

at short notice.

7 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Zero-hours contract employees

appear more likely to have a more

distant, transactional employment

relationship than the norm – one

where work is measured (and paid)

by the hour, with less engagement

in the long-term future of the

employment relationship.

There is still room for improvement in

the operation of zero-hours contracts.

This includes greater transparency

on employment status, codifying

procedures for the cancellation of

work at short notice and termination

of a zero-hours contract. This could

be achieved in part through greater

use of model contracts, but the CIPD

also believes all workers should be

legally entitled to a written copy of

their terms and conditions not later

than after two months in employment

(currently, under the Employment

Rights Act 1996, only employees are

entitled to this).

Employers who have chosen to place

the majority of the workforce on zero-

hours contracts should provide a clear

explanation to their workforce and

other stakeholders about the reasons

that led them to take this decision.

The available evidence does not

provide a strong case for further

legislation to regulate the use of

zero-hours contracts. However, if

policy-makers do want to intervene

further to improve the rights of

zero-hours contract workers, the

CIPD has suggested introducing

a right for zero-hours contract

workers to request regular hours

after they have been in employment

with an organisation for 12 months.

An outright ban on zero-hours

contracts could do more harm than

good. Prohibiting contracts that

give employees an option to turn

work down could lead to some of

them withdrawing from the labour

force. Employers with little concern

for their employees’ well-being

could simply change contracts to

guarantee a very small minimum

number of hours or replace zero-

hours contracts with casual labour.

The best way to improve the working

lives of the zero-hours contract

workforce is to help employers

understand why they need to develop

flexible and fair working practices

and how to implement them:

• Employers should consider

whether zero-hours contracts

are appropriate for their business

and check there aren’t alternative

means of providing flexibility

for the organisation, for example

through the use of annualised

hours or other flexible working

options.

• All zero-hours contract workers

should receive a written copy of

their terms and conditions. The

written statement should clarify

the intended employment status

and employers should conduct

regular reviews to check that

the reality of the employment

relationship matches the contract

of employment.

• Employers need to provide

training and guidance for line

managers to ensure they are

managing zero-hours workers

in line with their employment

status. Training must ensure that

line managers are aware that

zero-hours workers have a legal

right to work for other employers

when there is no work available

from their primary employer.

• Employers should provide zero-

hours contract workers with

reasonable compensation if pre-

arranged work is cancelled with

little or no notice. The CIPD believes

a reasonable minimum would be

to reimburse any travel expenses

incurred and provide at least an

hour’s pay as compensation.

• Employers should ensure there

are comparable rates of pay

for people doing the same job

regardless of differences in their

employment status.

‘An outright ban

on zero-hours

contracts could do

more harm than

good. Prohibiting

contracts that

give employees

an option to

turn work down

could lead to

some of them

withdrawing from

the labour force.’

8 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 9 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

‘The most common

reasons given

by employers

for using short-

hours contracts

are to manage

fluctuations in

demand.’

Short-hours contracts

Employer perceptions

About one in ten employers use

short-hours contracts offering

one to eight hours a week of

guaranteed employment.

Employers generally use short-

hours contracts for a relatively

small proportion of the workforce,

with the mean proportion

employed being 21.9%.

A best estimate for the number of

short-hours contract employees is

400,000.

The proportion of employers using

short-hours contracts is similar in

the private and public sectors, but

lower in the voluntary sector.

Short-hours contracts are most

prevalent in hotels, accommodation

and food and in retail.

Large organisations are much more

likely than small organisations to

use short-hours contracts.

The jobs most commonly carried

out by employees on short-hours

contracts are in administrative and

support roles, cleaning, caretaking,

driving, retail and various

hospitality-related functions.

The mean number of hours typically

worked by short-hours contract

workers is 11.4 hours each week. Just

5% of employers using short-hours

contract workers say the typical

working week is 30 hours or more.

Over two-fifths (43%) of employers

using short-hours contracts choose

to emphasise their role in shaping

working time patterns, whereas

16% place the employee in the

driving seat. Almost one-third

(31%) of employers say working

patterns are broadly the same each

week, in terms of hours per day

and days per week worked.

The most common reasons given

by employers for using short-

hours contracts are to manage

fluctuations in demand (mentioned

by 45% of employers), provide

flexibility for the individual (32%)

and provide cover for absences

(32%). Reducing costs is a

specific objective for 19%. Only

11% of employers using short-

hours contracts say they are used

in order to avoid the negative

publicity surrounding zero-hours

contracts.

Employee perceptions

According to the summer 2015 EO,

the median short-hours contract

involves five to eight hours’

guaranteed work each week

and the mean number of hours

usually worked is 9.2 hours.

Only 5% of short-hours contract

employees usually work over

32 hours each week.

Almost all short-hours contract

employees (94%) consider

themselves part-time and the vast

majority of these (91%) say it is

their choice to work part-time.

However, 25% of these ‘voluntary’

part-time employees would like

to work more hours. The most

common reason given for not

working more hours is a perception

that employers are unable to offer

more hours (mentioned by 70% of

short-hours contract employees

wanting to work more hours).

The proportion of short-hours

contract employees describing

their job as temporary (rather than

permanent) is 17%.

Two-thirds (68%) of short-hours

contract employees earn less than

£15,000 per year.

The proportion of short-hours

contract employees who are either

very satisfied or satisfied with

their jobs is 67%, higher than the

proportion for employees as a

9 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

whole (63%). However, part-time

short-hours contract employees

are less likely to be satisfied with

their jobs if they want to work

more hours.

Short-hours contract employees

have a very positive view of their

managers, with 75% either very

satisfied or satisfied with their

working relationship. They are

just as positive about working

relationships with colleagues as

other employees.

Short-hours contract employees

have an especially positive view of

their work–life balance, with 72%

agreeing or strongly agreeing that

they have the right balance.

Whereas 41% of employees

feel under uncomfortable and

excessive pressure at work at

least once or twice a week, the

proportion is just 26% for short-

hours contract employees. This

is in part because short-hours

contract employees are less likely

to think their workload is excessive.

Even allowing for this, however,

short-hours contract employees

report unusually low occurrences

of excessive pressure.

Short-hours contract employees

are more satisfied with their

job role than other employees

(75% satisfied or very satisfied,

compared with 63% for all

employees).

Three-fifths (60%) of short-hours

contract employees feel fully or

fairly well informed about what

is going on at work, compared

with 56% of all employees. As a

result, half (50%) are very satisfied

or satisfied with the opportunities

available to feed their views

upwards within the organisation,

compared with 44% for all

employees.

Conclusions

On the face of it, short-hours

contracts would appear close

substitutes for zero-hours

contracts. However, the evidence

suggests there are sometimes

quite substantial differences

between the two, both in how they

are used by employers and in their

suitability to employees.

These differences mean their

experience does not provide

any reliable guide to what might

happen if a minimum hours

guarantee – or the right to request

a minimum guaranteed number

of hours – was ever introduced

for existing zero-hours contract

employees.

10 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 11 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Despite accounting for less than

5% of the UK workforce, zero-hours

contracts remain controversial.

The limited quality and coverage

of much of the available data has

probably been a factor because

it is harder to refute claims made

about zero-hours contracts from

politicians, interest groups and

commentators on all sides of the

debate if the relevant evidence is

incomplete or inconsistent.

The Labour Force Survey (LFS) has

included a question about zero-

hours contracts since 2000 (see

Figure 1).

According to these data, the

number of employees on zero-

hours contracts has almost

tripled in three years. Much of

this reported increase may be the

result of the publicity surrounding

zero-hours contracts: as they have

become more widely understood,

more people have realised they are

covered by these arrangements.

The interdependence between

individual awareness, data, media

coverage and political debate is

illustrated by trends in the number

of UK-based web searches on zero-

hours contracts (see Figure 2).

Before 2012, searches for zero-

hours contracts were, in relative

terms, miniscule or non-existent.

From early 2013 until the middle

of 2015, the weekly number of

web searches appears to be on an

upwards trend. There are two very

large spikes in the data. The first

occurs in the week when the CIPD

first released its estimate of there

being 1 million zero-hours contract

workers, which was four times

greater than the LFS estimate at

the time (CIPD 2013b). The second

occurs early in the 2015 General

Election campaign when the Labour

Party leader, Ed Miliband, made a

speech on 1 April 2015 in which he

talked about ‘exploitative’ zero-

hours contracts and promised to

Introduction

Figure 1: People in employment on a zero-hours contract, 2000–15

UK, October–December quarter except 2014 and 2015 (April–June)

Source: Oce for National Statistics, Labour Force Survey

800

700

600

500

400

300

200

Thousands

100

2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014 20152000

0

11 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Figure 2: Interest in zero-hours contracts, 2011–15

UK web searches for ‘zero-hours contract’ topic. Data are scaled so that 100 is the week with the highest number of searches

Source: Google Trends

100

70

80

90

60

50

40

30

20

10

2011

0

29 March–5 April 2015:

Labour Party announces

plans to introduce

guaranteed hours of work

after 12 weeks’ employment

4–11 August 2013: CIPD publishes

estimate of 1 million zero-hours

workers, four times the ONS

estimate at the time

introduce a guaranteed minimum

number of hours after 12 weeks of

continuous employment. In both

cases, the news headlines and

publicity led to many web searches.

No doubt, in some cases, the result

was individuals realising that they

(or people they know) might be

employed on a zero-hours contract.

The Office for National Statistics

(ONS) supplements the LFS with

a biannual survey of employers.

The latest data cover a period of

two weeks in the second half of

January 2015, when there were

an estimated 1.5 million contracts

where work was carried out but

where no minimum number of

hours was guaranteed. This was

an increase of 100,000 on the

previous January (ONS 2015).

1

In

addition, there were 1.9 million

contracts with no guaranteed

hours where no work was carried

out during the reference period. An

unknown proportion of these may

also be zero-hours contracts.

Improvements to data collection in

the Labour Force Survey and the

new business survey help fill some

of the gaps in the evidence base

on zero-hours contracts. However,

data on the earnings of zero-hours

employees is limited. On average,

they earn much less than other

employees, but this is probably

because most zero-hours contracts

are in relatively low-paid sectors

and for less skilled jobs, rather

than because zero-hours contract

employees are paid less than other

employees for doing the same work.

The ONS business survey provides

estimates of the prevalence of

contracts with no guaranteed

minimum number of hours but it

does not collect data on how or

why employers use them.

Similarly, the LFS does not collect

data from employees on their

experience of zero-hours contracts

or on some important outcomes,

including well-being.

Many of these issues were covered

in the previous CIPD report

Zero-hours Contracts: Myth and

reality (CIPD 2013b). This report

updates and extends that analysis.

In particular, it includes data on

short-hours contract working,

which has to date received far less

attention in debates about the

quality and desirability of these

forms of work. This may in part be

due to the lack of official statistics.

The available evidence suggests

that short-hours contracts are

commonplace in retail: a survey

of union members in the sector

found that 10% were employed on

contracts that offer between one

and ten hours of guaranteed work

each week (USDAW 2014). As with

zero-hours contracts, there is no

universally accepted definition of

a short-hours contract. This report

uses a guaranteed minimum of

eight hours a week as the upper

limit for a short-hours contract.

The definitions used in this report

are explained in the glossary.

2012 2013 2014 2015

12 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 13 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Methodology

This report is based upon

analysis of survey data from both

employers and employees.

The employer perspective is

provided by the CIPD’s quarterly

Labour Market Outlook (LMO), a

representative sample survey of all

employers in the UK with two or

more employees.

Questions on zero-hours and

short-hours contracts were

included in the surveys conducted

in the spring and summer of 2015,

which generated responses from

1,013 employers and 931 employers

respectively (see CIPD 2015a and

CIPD 2015b for summaries of the

survey data and further information

about the composition of the

samples). The LMO data quoted

in this report are weighted to be

representative of the structure of

UK employment. In other words, a

finding that ‘x% of employers say

they use zero-hours contracts’ means

that zero-hours contracts are used

by employers who, between them,

employ x% of the UK workforce

with two or more employees.

2

Data were collected from some

additional employers who use

short-hours contracts. These

have been added to those surveyed

in the main spring and summer

surveys, producing a combined

dataset of 453 employers who use

either short-hours contracts or

zero-hours contracts (see Table 1).

3

Of these employers, 157 used short-

hours contracts, 209 used zero-

hours contracts and 88 used both

types of contract.

Analyses of the combined dataset

quoted in this report are weighted

by sector and employer size to be

representative of all employers

using short-hours or zero-hours

contracts during the spring and

summer of 2015.

The LFS collects data on

employees with zero-hours

contracts and this has been

supplemented by data from

the CIPD’s quarterly Employee

Outlook survey. This is a survey

of employees (including sole

traders) with participants drawn

from members of the YouGov Plc

UK panel of more than 350,000

individuals who have agreed to

take part in surveys.

Relevant questions were included

in the unpublished summer 2015

survey which allow comparisons

to be made between zero-

hours contract, short-hours

contract, temporary and part-

time employees. In total, 2,572

employees responded to the

survey. Fieldwork was undertaken

between 12 June and 7 September

2015. The figures presented in this

report have been weighted to be

representative of the UK workforce

in relation to sector (private,

public and voluntary), employer

size band, industry and full-time/

part-time working by gender. The

sample also includes boosts of

employees on zero-hours contracts

(to achieve a minimum of 300

responses), employees contracted

to work 1-8 hours (to achieve a

minimum of 100 responses) and

employees contracted to work 1-8

hours but who in practice work

more hours (to achieve a minimum

of 50 responses).

Table 1: Composition of combined dataset

Number of responses (unweighted)

Does your

organisation employ

people under a zero-

hours contract?

Does your organisation employ people under a short-hours contract?

Yes (up to 8 hours’

guaranteed work)

No (more than 8 hours’

guaranteed work) Impossible to say Row total

Yes 88 75 46 209

No 67 134 35 236

Don’t know 2 1 5 8

Column total 157 210 86 453

Source: CIPD combined Labour Market Outlook dataset, spring/summer 2015.

13 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Table 2: Employers using zero-hours and short-hours contracts (% of employers)

Yes (up to 8 hours’

guaranteed work)

No (more than 8 hours’

guaranteed work)

Employers using zero-hours contracts 23 26

Employers using short-hours contracts 6 8

Employers using zero-hours and short-hours contracts 2 4

Employers using neither zero-hours nor short-hours contracts 72 67

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook surveys

Use of zero-hours and short-hours

contracts

According to the LMO surveys

conducted in spring and summer

2015, about a quarter of employers

use zero-hours contracts, little

changed from the 2013 estimate

of 23%. About one in ten

employers use short-hours

contracts offering one to eight

hours a week of guaranteed

employment (see Table 2).

Only a small proportion of

employers use both types of

contract, although not necessarily

for the same types of work. Most

employers using these contracts

use one but not the other (84%

of employers using either type of

contract in summer 2015).

Employers generally use zero-

hours and short-hours contracts

for a relatively small proportion of

the workforce (see Figure 3). In

both cases, over half of employers

use them for less than 20% of the

workforce, presumably restricted

to specific roles or as a variable

margin to cover peaks and troughs

in workload. But there are a small

number of employers who have

chosen to make these contracts

their standard employment

model: 10% of zero-hours contract

employers and 8% of short-hours

contract employers use them for

over half of the workforce.

Employer perspectives

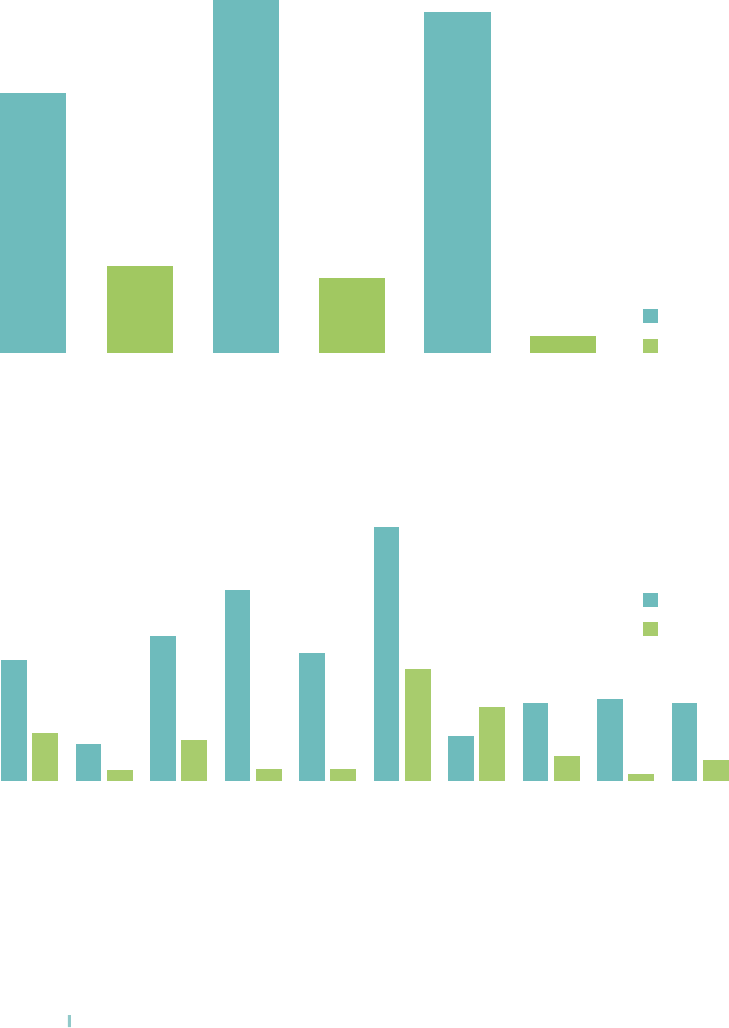

Figure 3: Proportion of an organisation’s workforce employed on zero-hours and short-hours contracts (%)

1–10

1–10

11–20

11–20

21–30

21–30

31–40

31–40

41–50

41–50

51–60

51–60

61–70

61–70

71–80

71–80

81–90

81–90

91–100

91–100

Base: Employers who used zero-hours contracts/short-hours contracts and were able to estimate the proportion of the workforce on them (n=330 and n=106)

Source: CIPD combined Labour Market Outlook dataset, spring/summer 2015

Zero-hours contracts

Mean = 19.7

Short-hours contracts

Mean = 21.9

42

35

10

17

5

8

2

1

3

7

2

3

2 2

3

1

1

0

2 2

14 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 15 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

In spring 2015, the mean

proportion of the workforce

employed on zero-hours contracts

in the private sector organisations

using them was 27%, whereas it

was 11% in the public and voluntary

sectors – again, similar proportions

to 2013. Almost all organisations

with more than half of the

workforce on zero-hours contracts

are in the private sector.

A best estimate for the number

of zero-hours contract employees

at spring/summer 2015 is

1.3 million, which is an increase

from the 2013 estimate of 1 million.

A best estimate for the number

of short-hours contract employees

is 400,000 (see box for details of

these calculations).

Decisions on whether or not to use

these types of contract can change.

In spring 2015, 6% of employers

who didn’t use zero-hours

contracts at that time had used

them in the past. At the same time,

1% of employers who had never

used zero-hours contracts planned

to introduce them shortly and 2%

were considering their introduction.

Another 12% had no plans but

might consider their use in the

medium term. Nevertheless, over

three-quarters (78%) of employers

who have never used zero-hours

contracts don’t think they will ever

use them. Half the employers in

this group don’t think they need

that level of flexibility. There are

also concerns about a negative

impact on employee engagement

(mentioned by 44% of employers

who will never introduce zero-

hours contracts), their exploitative

nature (33%) and the negative

publicity that zero-hours contracts

have generated (16%).

This suggests there may be

limited scope for further increases

in the proportion of employers

using zero-hours contracts. This

doesn’t necessarily mean the

number of people employed on

these contracts is at or near a

peak. Growth could still arise if

organisations already using zero-

hours contracts make greater use

of them.

Calculation of estimates of numbers of zero-hours and short-hours contract employees

Numbers of zero-hours and short-hours contract employees are estimated using the following calculation:

[Number of employees] x [% of employers using zero-hours/short-hours contracts] x [% of workforce on

zero-hours/short-hours contracts]

Where:

The number of employees in businesses with two or more employees is 27.666 million, taken from the whole

economy table of the 2015 UK business population estimates.

The proportions of employers using zero-hours contracts/short-hours contracts are 24.6% and 6.9%

(arithmetic means of employment-weighted percentages from the spring and summer 2015 LMO surveys,

see Table 2).

The proportions of the workforce on zero-hours/short-hours contracts where these are used are 19.7% and

21.9% (employment-weighted percentages taken from the combined LMO dataset, see Figure 3).

Multiplying these together gives estimates of 1.34 million for zero-hours contracts and 415,000 for short-

hours contracts. Disaggregating the calculation using six employee size bands produces slightly different

estimates (1.25 million and 400,000), so both estimates have been rounded to the nearest 100,000 to avoid

appearing unduly precise.

Note that rounding does not correct for all the sources of uncertainty in these calculations. Other potential

sources of variation include item non-response (in particular, 30% of employers using zero-hours contracts

and 40% of employers using short-hours contracts don’t know what proportion of their workforce

are employed on these contracts), non-response bias in general, and imperfect understanding among

employers of these contracts (even though definitions were provided).

15 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Variation across employers in the

use of zero-hours and short-hours

contracts

In line with previous CIPD research,

employers in the public and

voluntary sectors are more likely

to use zero-hours contracts than

private sector employers (see

Figure 4). This is not the case with

short-hours contracts, where the

proportion using them is very similar

in the private and public sectors, but

lower in the voluntary sector.

These differences by sector

arise because of significant

differences between industries in

the use of both types of contract

(see Figure 5). Zero-hours contracts

are most often used by employers

in hotels, accommodation and

food, health and social work (which

includes social care), education and

the voluntary sector.

4

Short-hours

contracts are most prevalent in

hotels, accommodation and food

and in retail.

Large organisations are much

more likely than small

organisations to use zero-hours

contracts and short-hours

contracts (see Figure 6).

Figure 4: Employer use of zero-hours and short-hours contracts, by sector (%)

Private sector Public sector Voluntary sector

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, summer 2015.

3

31

8

32

9

24

Short-hours contracts

Zero-hours contracts

Figure 5: Employer use of zero-hours and short-hour contracts, by industry (%)

Source: CIPD combined Labour Market Outlook survey, summer 2015

29

9

35

46

31

61

11

19

20

19

12

3

10

3

3

27

18

6

2

5

Agriculture, construction etc.

Manufacturing

Education

Health and social work

Voluntary

Hotels, catering, accommodation

Retail

Transportation, communication

Finance, business services

Central and local government

Short-hours contracts

Zero-hours contracts

16 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 17 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

How employers use zero-hours

and short-hours contracts

The majority of organisations that

use zero-hours and short-hours

contract workers employ them

directly, rather than through an

employment agency, although a

small minority use both direct and

indirect employment models (see

Table 3).

Employers use zero-hours and

short-hours contract workers for a

variety of jobs (see Figure 7). The

jobs most commonly mentioned by

employers are administrative and

support roles, care work, cleaning

and various hospitality-related

functions. Some more skilled

jobs (nursing, IT, teaching) are

also mentioned. The distribution

of roles for short-hours contract

workers is similar. The main

differences are that employers

using short-hours contracts are

more likely to highlight driver,

caretaker and retail roles and

less likely to be using them for

administrative and support staff,

cleaners and nurses.

Figure 6: Employer use of zero-hours and short-hours contracts, by employee size band (%)

Source: CIPD combined Labour Market Outlook survey, summer 2015

6

5

10

4

10

1

19

7

33

11

22

15

Micro

(2–9 employees)

Small

(10–49 employees)

Medium

(50–249 employees)

250–999

employees

1,000–9,999

employees

10,000+

employees

Short-hours contracts

Zero-hours contracts

Table 3: Arrangements for the employment of zero-hours and short-hours contract workers (%)

Employers using

zero-hours contracts

(n=215)

Employers using

short-hours contracts

(n=104)

Direct employment 78 75

Employment via an agency 6 15

Both 15 7

Sources: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (zero-hours contracts); combined CIPD Labour Market Outlook dataset,

spring/summer 2015 (short-hours contracts)

17 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Employers generally use zero-

hours and short-hours contracts

for a limited number of specific

jobs rather than for a wide range

of different ones. The list of jobs

shown in Figure 7 has 27 different

categories, but 83% of employers

using zero-hours contracts and

86% of employers using short-

hours contracts use them in no

more than three different roles.

Employers were asked, ‘On

average, how many hours per

week does a member of staff

employed under a zero-hours

contract/short-hours contract

work at your organisation?’ Over

two-fifths of employers using

zero-hours contracts and a third

of employers using short-hours

contracts were unable to provide

an answer. Where an average or

Figure 7: Roles filled by zero-hours and short-hours contract workers

Administrative roles

Cleaners

Caterers/waiters or waitresses

Care/social workers

Secretaries, PAs etc.

Support staff

Other

Nurses

Caretaker/cleaner

Retail workers

Chefs or cooks

Teachers/tutors

Call centre/customer services

Salesforce

IT staff

Production/machine operators

Labourers

Doctors

Consultants

Other hotel, catering or leisure

Drivers

Skilled trades workers

Security staff

Researchers

Legal staff

HR staff

Media staff

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (zero-hours contracts, n=215);

combined CIPD Labour Market Outlook dataset, spring/summer 2015 (short-hours contracts, n=157)

5 10 15 20 25 30

0

Short-hours contracts

Zero-hours contracts

% of employers

18 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 19 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

typical number of hours could

be provided, zero-hours contract

workers usually work considerably

longer hours than short-hours

contract workers (see Figure 8).

The mean number of hours

typically worked by zero-

hours contract workers is 19.4,

compared with 11.4 for short-hours

contract workers. Whereas 20%

of employers with zero-hours

contract workers typically employ

them for 30 or more hours each

week – which, for statistical

purposes, would count as full-time

employment – this is the case for

just 5% of employers using short-

hours contract workers.

Employers were also asked about

the qualitative nature of their

working time arrangements:

‘Which description best describes

the typical working hours pattern

of a member of staff that is

employed under a zero-hours

contract/short-hours contract at

your organisation?’ Over two-fifths

of employers using both types

of contract choose to emphasise

their role in driving working time

patterns (see Table 4). One in

six place the employee in the

driving seat. About two-fifths of

employers using each type of

contract focus on the variability

of working time. Here, there is a

noticeable difference between the

two contracts. Employers using

zero-hours contracts are more

likely to emphasise variability and

the impossibility of being able to

describe a typical working pattern.

Employers using short-hours

contracts are more likely to stress

a degree of regularity in the hours

and days worked each week.

5

‘The mean number

of hours typically

worked by zero-

hours contract

workers is 19.4,

compared with

11.4 for short-

hours contract

workers.’

Short-hours contracts

Zero-hours contracts

Figure 8: Distribution of typical weekly hours for zero-hours and short-hours contract workers (%)

35

30

25

20

15

10

5

0

Up to 5

hours

6–10

hours

11–15

hours

16–20

hours

21–25

hours

26–30

hours

31–35

hours

36–40

hours

41–45

hours

46–50

hours

51–55

hours

56–60

hours

60+

hours

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (zero-hours contracts, n=210);

combined CIPD Labour Market Outlook dataset, spring/summer 2015 (short-hours contracts, n=71)

19 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Why employers use zero-hours

and short-hours contracts

The employment and management

practices used by an organisation

depend, among other factors, on

its strategic orientation, market

positioning, how it competes

and its internal culture (see CIPD

2014b, Wu et al 2014, Wood et al

2013, Winterbotham et al 2014).

Data collected in the summer 2015

LMO captured various aspects

of organisation strategy and

mindset.

6

In general, these factors

seem to account for little of the

variation across employers in the

use of zero-hours and short-hours

contracts (see Table 5).

Table 4: Typical working hours patterns of zero-hours and short-hours contract workers (%)

Employers using

zero-hours contracts

(n=215)

Employers using

short-hours contracts

(n=104)

Working hours are driven largely by the employer 44 43

Working hours are driven by the individual 15 16

Hours are broadly the same each week 14 21

Hours vary greatly each week 10 3

Working days are broadly the same each week 3 10

Working days vary greatly each week 3 1

It is impossible to tell 9 4

Don’t know 2 2

Sources: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (zero-hours contracts); combined CIPD Labour Market Outlook dataset,

spring/summer 2015 (short-hours contracts)

Table 5: Use of zero-hours and short-hours contracts, by product/service strategy, organisation

culture and mindset (%)

Employers using

zero-hours contracts

Employers using

short-hours contracts

Product/service strategy

Premium quality (n=560) 27 5

Basic/standard quality (n=295) 27 14

Organisation culture

Family (n=354) 24 7

Structured (n=306) 31 8

Entrepreneurial (n=109) 20 5

Results-oriented (n=160) 23 12

Organisation mindset

Survivor (n=200) 26 8

Cost-cutter (n=131) 12 11

Balanced investor (n=165) 28 7

People-focused investor (n=110) 28 10

Capital-focused investor (n=128) 30 5

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, summer 2015

20 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 21 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

The summer 2015 LMO also asked

respondents to identify current

priorities for their organisation

(see Figure 9). Again, employers

using zero-hours and short-

hours contracts tend not to differ

much from other employers.

However, employers using zero-

hours contracts are more likely

to give priority to increasing

organisational responsiveness to

change, regulatory compliance and

improving reputation and brand.

It is not possible to determine

whether the use of zero-hours

and short-hours contracts is

determined by business priorities

or whether business priorities

might be influenced by the use of

zero-hours contracts and short-

hours contracts. Using zero-hours

contracts is an understandable

strategy for organisations seeking

to improve their ability to deploy

labour flexibly and quickly.

However, the negative publicity

attached to zero-hours contracts

could also be the reason why

employers using them are more

likely to be concerned about

reputation and brand (and,

perhaps, regulatory compliance).

The use of zero-hours and short-

hours contracts sometimes forms

part of a broader approach to

the flexible deployment of labour.

Both zero-hours and short-hours

contracts are more common in

organisations where 11% or more

of the workforce are temporary

contract workers (see Table 6).

Table 6: Use of zero-hours and short-hours contracts, by presence of temporary contract workers (%)

% of workforce made up of workers on

temporary contracts

Employers using

zero-hours contracts

Employers using

short-hours contracts

0% (n=339) 9 3

1–10% (n=318) 26 6

11–25% (n=122) 45 16

26%+ (n=147) 42 15

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, summer 2015

Figure 9: Current priorities for the organisation (%)

Cost management

Growth of market share in new or existing markets

Customer service improvement

Improving productivity

Improving organisational responsiveness to change

Regulatory compliance

Product innovation and quality improvement

Increasing sustainability

Improving corporate responsibility, reputation and brand

Significant refocus of business direction

% of employers identifying these areas as a current priority

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (n=929)

10 20 30 40 50 60 70

0

Employers using zero-hours contracts

Employers using short-hours contracts

All employers

21 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Employers who used zero-hours

and short-hours contracts were

asked a specific question about

their reasons for using them (see

Figure 10). The most common

reasons given for using both

types of contract are to manage

fluctuations in demand, provide

flexibility for the individual and

provide cover for absences, both

expected (such as holidays) and

unexpected (such as sickness

absence). Reducing costs is a

specific objective for about one-

fifth of employers using both types

of contract and some employers

also mention the costs associated

with employment of agency

workers (both fees and meeting

regulatory requirements). Only

11% of employers using short-

hours contracts say they use them

in order to avoid the negative

publicity surrounding zero-hours

contracts.

Almost half (47%) of employers

using zero-hours contracts see

them as a long-term feature of

their workforce strategy, likely

to still be in use in four or more

years’ time. In contrast, just 13%

of employers using zero-hours

contracts see them as a short-term

element in their plans, unlikely to

be used in 12 months’ time, with

29% thinking they might have a

lifespan of two to three years –

very similar responses to those

provided by employers in 2013.

Employers in the public sector

and employers with more than

10% of the workforce on zero-

hours contracts are more likely to

consider them part of their long-

term workforce strategy.

The priorities, mindset, market

positioning and internal culture of

an organisation are not, in general,

significant influences on whether

or not it uses zero-hours or short-

hours contracts. Nor indeed

are industry or sector, although

organisation size does increase

the likelihood of using these

contracts. The main influences on

whether or not these contracts

are used appear to be the nature

of the work, the variability and

predictability of customer demand

and staffing requirements, and

the extent to which they are part

of a broader workforce flexibility

agenda. Employee preferences

also play a role, as does a desire to

manage costs.

7

The practical operation of zero-

hours contracts

One strand of the debate

around zero-hours contracts has

centred on their advantages and

disadvantages and on whether

or not it would be desirable (or

feasible) to restrict or prohibit their

use. A second strand has focused

on specific issues associated with

how zero-hours contracts are used

in the workplace and whether

there is a case for regulations

governing how they are used.

One example is exclusivity

clauses, which the Government

has prohibited. Other issues

that have featured in the debate

include employment status, the

Figure 10: Reasons why employers use zero-hours and short-hours contracts (%)

Manage fluctuations in demand

Provide flexibility for individual

Provide coverage for staff absences

Part of a broader strategy to keep costs down

Uncertain business conditions

To avoid agency fees

To retain workers rather than make them redundant

Avoid Agency Workers Regulations costs

Other

Legacy within the organisation

Don’t know

No particular reason

To avoid negative publicity of zero-hours contracts

Respondents could select more than one reason

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook surveys, spring 2015 (zero-hours contracts, n=215);

combined CIPD Labour Market Outlook dataset, spring/summer 2015 (short-hours contracts, n=104)

Zero-hours contracts

Short-hours contracts

45

66

32

51

32

46

19

21

23

18

11

14

17

13

6

10

6

8

14

6

1

2

2

1

11

22 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 23 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

information provided to employees

(including notice of when work is

not available or when a zero-hours

contract is terminated) and their

treatment in terms of pay and

other benefits. Data covering these

topics were collected in the spring

2015 LMO.

Employers using zero-hours

contracts were asked: ‘In practice,

how does your organisation

generally classify the employment

status of staff who are on a zero-

hours contract?’ The picture is

similar to 2013: most employers

of zero-hours contract staff (67%)

classify them as employees, with

19% classifying them as workers, 5%

as self-employed, 6% not classifying

their status and 1% unaware.

8

A large majority of employers using

zero-hours contracts (81%) provide

them with a written contract, 8%

do not provide a contract and

8% say it varies, with 3% unsure

because workers are supplied by

a recruitment agency. Where a

written contract is provided, 86%

of these employers say it records

employment status. Of course,

whatever is stated in a contract

may not match employment status

in law. This ultimately would be

determined by a tribunal on the

basis of all the relevant evidence,

including (but not restricted

to) the contents of the written

contract of employment.

Employers were asked whether

employees on zero-hours

contracts are under a contractual

obligation to accept work if it

is offered to them. They were

also asked: ‘Regardless of what

the contract says, are staff on

zero-hours contracts within your

organisation expected to accept

work in practice?’ More than half of

employers (58%) give employees

the freedom in contract to turn

work down and say they

also honour this in practice (see

Table 7). However, a fifth of

employers (21%) say that contracts

give workers the right to turn work

down when, in practice, they are

always or sometimes expected to

accept all work offered to them.

This would appear to violate the

spirit, and possibly the letter, of

the employment contract.

Employers were also asked

whether they have a contractual

provision, practice or policy on the

amount of notice given to staff on

zero-hours contracts when a shift

is cancelled or when the company’s

relationship with the individual

is terminated (see Table 8). Two-

thirds (66%) of employers say

they have some form of policy or

practice on notice of termination,

compared with 55% in 2013. Less

than half of employers (45%) say

they have policies or practices

when it comes to cancelling a

shift. There is some uncertainty

here among employers, with 20%

unsure what the position is in at

least one of these situations.

Table 7: Contractual and practical obligations on zero-hours contract workers to accept all work oered

% of employers using zero-hours contracts, excluding ‘don’t know’ responses (n=205)

Contractual obligation Regardless of contract, whether practical obligation exists

Yes – obliged

to accept

No – free to

turn down Sometimes Row totals

Yes – obliged to accept 13 1 0 14

No – free to turn down 11 58 10 79

Sometimes 2 <0.5 6 8

Column totals 25 59 15

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015.

Table 8: Existence of contractual provision, practice or policy on amount of notice given to zero-hours contract workers

% of employers using zero-hours contracts (n=215)

Notification of

cancellation of shift

Notification of termination

Yes No Don’t know Row totals

Yes 41 2 2 45

No 21 17 1 38

Don’t know 4 1 12 17

Column totals 66 20 15

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015.

23 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Employers were asked to provide

additional information on their

policies or procedures, if they had

them. The number of answers

in each case was too small for

statistical analysis but some

common themes emerged. When

it came to cancellation of a shift,

some employers emphasise this

rarely or never happens, at least

once a rota has been drawn up.

The most commonly mentioned

notice periods are 24 or 48 hours

before a shift commences. Some

employers specifically say they

will pay the employee if the shift

is cancelled at shorter notice. A

number of employers do not allow

employees to cancel shifts once

they have accepted them, whereas

others also have minimum notice

periods for employees who want

to cancel work at short notice. As

for termination of the employment

relationship, some employers say

they treat zero-hours contract

employees in the same way as

other employees when it comes to

procedures and calculating notice

periods. Otherwise, commonly

specified notice periods are one

week and one month.

The majority of employers using

zero-hours contracts (63%) pay

zero-hours contract staff about

the same hourly rate as those on a

permanent contract doing the same

job. Some employers (16%) pay a

higher rate and others (9%) pay a

lower rate. A small proportion (4%)

don’t know the relative pay rate and

for 9% the question doesn’t apply,

presumably because there are no

situations where people with zero-

hours contracts and permanent

contracts are doing the same job.

As the proportion of the workforce

on zero-hours contracts increases,

it becomes less and less likely that

people on zero-hours contracts and

permanent contracts are doing the

same job.

Over four-fifths (82%) of

employers using zero-hours

contract workers say they are

eligible for company training and

development, with just 13% saying

this is not the case.

Entitlements of zero-hours contract

staff to a range of benefits

and rights – many specified in

employment legislation – depend

to a large extent on whether or not

their employer is one of the 67%

that classifies them as employees

(see Figure 11).

Source: CIPD Labour Market Outlook survey, spring 2015 (n=215)

Employers who do not treat zero-hours contract workers as employees

All employers of zero-hours contract workers

Employers who treat zero-hours contract workers as employees

Figure 11: Benefits available to people on zero-hours contracts (%)

Right to receive written statement of terms and conditions

Annual paid leave

Statutory minimum notice

Right not to be unfairly dismissed (after 2 years’ service)

Pension auto-enrolment

Statutory sick pay

Statutory maternity, paternity, adoption leave and pay

Statutory redundancy pay (after 2 years’ service)

Right to request flexible working

Occupational sick pay

None – no benefits are available

69

61

45

71

59

35

69

57

33

65

51

23

56

48

31

61

48

22

53

43

24

48

36

14

44

33

11

21

26

10

5

14

31

24 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives 25 Zero-hours and short-hours contracts in the UK: Employer and employee perspectives

Employers are most likely to say

people on zero-hours contracts are

entitled to annual paid leave (61%),

the right to receive a statement of

written terms and conditions (59%)

and the statutory minimum notice

period (57%). Employers are least

likely to give them entitlement to

occupational sick pay (21%), which