REPORT

Review of The Star Pty Ltd

Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of

the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

VOLUME 2

Report of the Inquiry under section 143 of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

Published 31 August 2022

© State of NSW through the Inquiry under section 143 of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

_______________________________________________

CONTENTS

Contents

Volume 1

Chapter 1 Executive Summary

Chapter 2 Previous Reviews of The Star

Chapter 3 Developments in the Casino Landscape in Australia since the 2016 Review

Chapter 4 The Nature of this Review

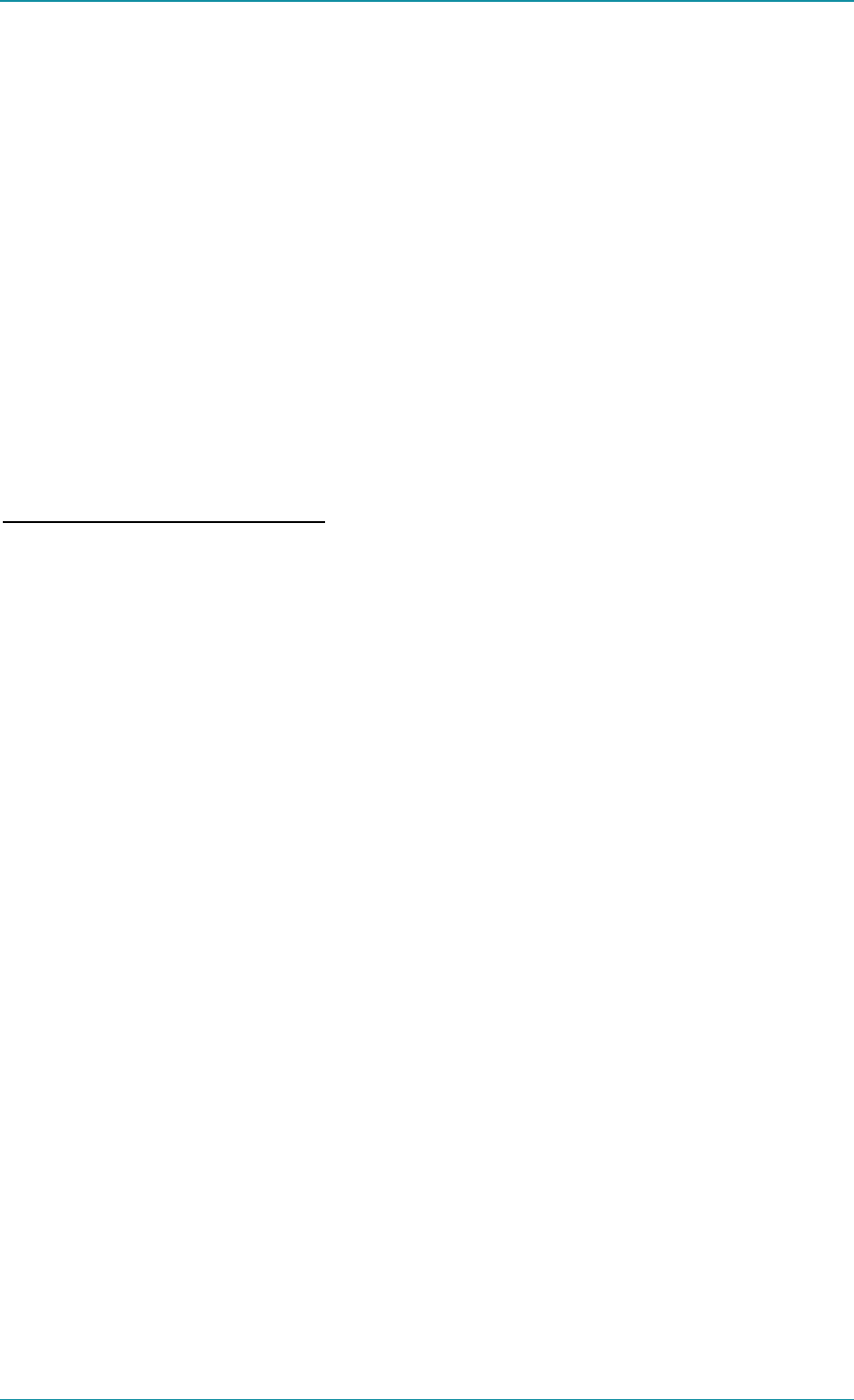

Chapter 5 The Regulatory Environment

Chapter 6 The Test of Suitability

Chapter 7 Procedural History of this Review

Chapter 8 Governance and Management Structure of The Star and Star Entertainment

Chapter 9 Departures from Star Entertainment during the public hearings and their impact

Chapter 10 Risks of Money Laundering and Criminal Infiltration in Casinos

Chapter 11 Developments in the VIP Casino Market in North Asia and their Significance

Chapter 12 The use of CUP Cards at The Star

Volume 2

Chapter 13 The Star’s Dealings with Suncity since 2016 ........................................................... 1

Chapter 13.1 Introduction ............................................................................................................ 2

Chapter 13.2 The Establishment of Salon 95 .............................................................................. 3

13.2.1 The 2017 Rebate Agreement ................................................................................................ 3

13.2.2 The layout of Salon 95 ......................................................................................................... 4

Chapter 13.3 Knowingly Misleading Liquor & Gaming NSW ................................................... 6

13.3.1 Contemplation of a cage or buy-in desk in Salon 95 ........................................................... 6

13.3.2 The submission to Liquor & Gaming NSW dated 12 October 2017 ................................... 9

13.3.3 Further communication with L&GNSW ............................................................................ 11

13.3.4 The Star’s breach of the Casino Operations Agreement .................................................... 12

Chapter 13.4 The Unauthorised use of the Service Desk in Salon 95 ....................................... 13

13.4.1 The commencement of the service desk: mid-April 2018 ................................................. 13

13.4.2 Large cash payments at the service desk: 18 April 2018 ................................................... 21

13.4.3 The completed risk assessment: 27 April 2018 .................................................................. 23

13.4.4 Chips for cash exchanges at the service desk: 8 May 2018 ............................................... 24

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

i

CONTENTS

Chapter 13.5 The Star’s Inappropriate Response to the Unauthorised use of the Service Desk in

Salon 95 ..................................................................................................................................... 28

13.5.1 The first warning letter: 10 May 2018 ...............................................................................28

13.5.2 Mr McGregor calls out Suncity’s conduct in Salon 95: 14 May 2018 ..............................29

13.5.3 “Operation Money Bags”: 15 and 16 May 2018 ................................................................30

13.5.4 Belated reaction from Senior Management: 15 and 16 May 2018 ....................................31

13.5.5 The Service Desk SOP: 23 May 2018 ...............................................................................34

13.5.6 The second warning letter: 8 June 2018............................................................................. 36

13.5.7 The Salon 95 balcony blind-spot footage: 15 June 2018 ...................................................39

13.5.8 Renewal of the 2017 Rebate Agreement: 21 June 2018 .................................................... 40

13.5.9 Inadequate disclosure to the Board of issues in Salon 95: 26 July 2018 ...........................41

Chapter 13.6 The Review of Salon 95 By Mr Stevens in 2019 ................................................. 43

13.6.1 Salon 95 remains in operation: late 2018 to early 2019 .....................................................43

13.6.2 Mr Stevens’ conducts his review: March to May 2019 ..................................................... 45

13.6.3 Mr Stevens’ report on Salon 95: 23 May 2019 ..................................................................45

13.6.4 The email from Mr Tomkins: 24 June 2019 ......................................................................46

13.6.5 Mr Buchanan’s reliance on Mr Stevens’ report ................................................................. 47

13.6.6 Further concerning conduct in Salon 95 in 2019 ............................................................... 47

Chapter 13.7 The Hong Kong Jockey Club Report ................................................................... 48

Chapter 13.8 Those who knew: the dissemination of the Hong Kong Jockey Club Report at Star

Entertainment ............................................................................................................................. 51

Chapter 13.9 Mr Buchanan and Mr Houlihan’s Trip to Hong Kong in July 2019 .................... 57

Chapter 13.10 Media Allegations Concerning Suncity in 2019

................................................ 58

Chapter 13.11 The Star’s Disclosures to the Board in response to the 2019 Media Allegations

................................................................................................................................................... 60

Chapter 13.12 The Star’s Disclosures to the Authority in response to the 2019 Media Allegations

................................................................................................................................................... 65

Chapter 13.13 Suncity moves to Salon 82 ................................................................................. 70

13.13.1 No updated risk assessment ........................................................................................ 70

13.13.2 Suncity moves from Salon 95 to Salon 82: September 2019 ......................................71

Chapter 13.14 Relevant Evidence given to the Bergin Inquiry ................................................. 74

13.14.1 Mr Hawkins’ evidence before the Bergin Inquiry: 4 August 2020 .................................. 74

13.14.2 The correctness of Mr Hawkins’ answers to the Bergin Inquiry .....................................76

13.14.3 Mr Hawkins’ explanation for his evidence to the Bergin Inquiry ....................................78

13.14.4 Conclusions concerning Mr Hawkins’ evidence to the Bergin Inquiry ........................... 78

13.14.4 Ms Arnott’s evidence before the Bergin Inquiry: 3 and 6 August 2020 ..........................80

13.14.5 Disclosure to this Review of the events in Salon 95 ........................................................82

Chapter 13.15 The Evolving Due Diligence Reports of Mr Buchanan ..................................... 82

13.15.1 The 1 October 2020 memorandum ..................................................................................82

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

ii

CONTENTS

13.15.2 Mr Buchanan’s meetings with Mr Power and Mr Houlihan ............................................85

13.15.3 Changes between the 1 October 2020 and 24 November 2020 versions ......................... 87

13.15.4 Mr Power’s deletions in the marked up copy ................................................................... 89

13.15.5 Conclusions regarding the evolution of Mr Buchanan’s memorandum ..........................91

Chapter 13.16 The Final Due Diligence Assessments of Suncity and Alvin Chau ................... 93

13.16.1 The question of “good repute” ......................................................................................... 93

13.16.2 The Project Congo memorandum: 16 August 2021 .........................................................94

13.16.3 Further decisions to “Maintain customer relationship” with Mr Chau: 18 August 2021

and 6 December 2021 ................................................................................................................... 96

13.16.4 Withdrawal of Licence issued to Mr Chau: 14 December 2021 ...................................... 98

13.16.5 A most concerning state of affairs ...................................................................................99

Chapter 13.17 Consideration of the Lawfulness of the Service Desk in Salon 95 .................. 100

13.17.1 The legal issues .............................................................................................................. 100

13.17.2 Sections 12, 31 and 32 of the Unlawful Gambling Act 1998 (NSW) ............................102

13.17.3 Section 124 of the Casino Control Act ..........................................................................105

13.17.4 Section 70 of the Casino Control Act ............................................................................115

Chapter 13.18 Conclusions and Recommendations ................................................................ 119

Chapter 14 The end of junkets ..................................................................................................140

Chapter 14.1 Introduction ........................................................................................................ 141

Chapter 14.2 Evidence to the Bergin Inquiry .......................................................................... 141

Chapter 14.3. Star Entertainment’s announcement in September 2020

.................................. 142

Chapter 14.4 Mr Bekier’s 6 May 2021 email to the Authority

................................................ 142

Chapter 14.5 The intentions of senior management ................................................................ 143

Chapter 14.6 The intentions of the Board ................................................................................ 145

Chapter 14.7 Conclusions and recommendations .................................................................... 146

Chapter 15 Misrepresentations to the Bank of China Macau ............................................... 149

Chapter 15. 1 Introduction ....................................................................................................... 150

Chapter 15.2 The Relevant Conduct ........................................................................................ 151

Chapter 15.3 Extent of the Conduct

......................................................................................... 154

Chapter 15.4 The Investigation of the Conduct by Star Entertainment ................................... 156

Chapter 15.5 Conclusions ........................................................................................................ 158

Chapter 16 The Closure of Star Entertainment’s Bank Accounts in Macau and the Response

...................................................................................................................................................... 162

Chapter 16.1 Introduction

........................................................................................................ 163

Chapter 16.2 Establishment of EEIS ....................................................................................... 164

Chapter 16.3 Use of the EEIS Bank of China Hong Kong Accounts ...................................... 165

Chapter 16.4 Closure of The Star’s BOC Macau Accounts .................................................... 166

Chapter 16.5 The Kuan Koi Arrangements ............................................................................. 167

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

iii

______________________________________________

CONTENTS

Chapter 16.6 Activities of EEIS in 2018 and 2019.................................................................. 185

Chapter 16.7 Conclusions ........................................................................................................ 214

Chapter 17 The Conduct of Star Entertainment’s International VIP Team since 2016 ..... 230

Chapter 17.1 Introduction

........................................................................................................ 231

Chapter 17.2 The organisational structure of the International VIP Team in the Relevant Period

................................................................................................................................................. 232

Chapter 17.3. Mr John Chong

.................................................................................................. 232

Chapter 17.4 Mr Marcus Lim .................................................................................................. 236

Chapter 17.5 Mr Simon Kim ................................................................................................... 241

Chapter 17.6 The closure of Star Entertainment’s overseas offices ........................................ 243

Chapter 17.7 Inadequate Supervision and Management of the International VIP Team

........ 243

Chapter 18 The KPMG Reports ............................................................................................... 250

Chapter 18.1 Commissioning of the reports ............................................................................ 251

Chapter 18.2 KPMG’s reports dated 16 May 2018

................................................................. 253

Chapter 18.3 Audit Committee meeting of 23 May 2018 and reaction to KPMG’s reports ... 255

Chapter 18.4 Subsequent meetings with KPMG ..................................................................... 259

Chapter 18.5 KPMG confirms its findings .............................................................................. 261

Chapter 18.6 Implementation of KPMG’s recommendations ................................................. 262

Chapter 18.7 Claiming legal professional privilege for the KPMG reports ............................ 263

Chapter 18.8 Failure to disclose KPMG’s reports to AUSTRAC ........................................... 267

Chapter 18.9 Failure to disclose KPMG’s reports to the Authority ........................................ 268

Chapter 18.10 Failure to disclose KPMG’s reports to the market ........................................... 269

Chapter 19 Star Entertainment’s Practices in Claiming Legal Professional Privilege ....... 276

Chapter 19.1 Introduction

........................................................................................................ 277

Chapter 19.2 Key principles .................................................................................................... 277

Chapter 19.3 Practice in relation to legal professional privilege claims .................................. 277

Chapter 19.4 Conclusions and recommendations .................................................................... 281

Volume 3

Chapter 20 Overall Assessment of Star Entertainment’s AML/CTF Program and associated

processes

Chapter 21 Prevention of Criminal Infiltration

Chapter 22 Gambling Duty Payable by The Star to the NSW Government

Chapter 23 Harm Minimisation and Responsible Gambling

Chapter 24 Controlled Contracts, Gambling Chips and Free Bet Vouchers

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

iv

CONTENTS

Chapter 25 The Use of Standard Operating Procedures at The Star

Chapter 26 Assessment of the Governance and Culture of Star Entertainment since 2016

Chapter 27 Suitability

Appendices

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

v

1

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

Chapter 13

The Star’s Dealings with Suncity since 2016

2

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Chapter 13. The Star’s Dealings with

Suncity since 2016

Chapter 13.1 Introduction

1. This Chapter considers The Star’s dealings with the Suncity Group (Suncity) since 2016.

During the Relevant Period, Suncity had various global business interests and was

associated with a number of publicly listed companies in Hong Kong. Suncity’s business

interests included the provision of VIP junket services throughout Asia. Mr Cheok Wa

Chau (also known as Alvin Chau) was the founder of Suncity. Between 2011 and 2016,

and between 2017 and October 2020, Mr Chau held the CCF

1

for, and therefore funded, a

particular junket group of which Mr Kit Lon Iek,

an employee of Suncity,

2

was the junket

promoter (Iek junket).

3

The Star had dealt with junkets funded by Mr Chau since 2011.

4

2.

For the financial years 2017, 2018 and 2019, the Iek junket turned over approximately

$1.29 billion, $2.29 billion and $1.27 billion respectively at The Star by way of non-

negotiable chips.

5

By September 2017, Suncity was The Star’s largest junket customer.

6

On 16 February 2018, the Board of Star Entertainment approved an increase in Mr Chau’s

CCF from $50 million to $80 million.

7

The Iek junket was one of the largest in terms of

turnover with which The Star dealt during the Relevant Period.

3.

An important feature of The Star’s relationship with Suncity was the private and exclusive

gaming room that The Star made available to the Iek junket. That gaming room was called

“Salon 95”. From late 2017, Suncity was the only junket operating at The Star that had its

own, exclusive gaming salon.

8

The events that took place in that salon, many of which

were captured on CCTV footage or recorded in contemporaneous emails and records, were

an important focus of the Review’s investigations and public hearings.

4.

While The Star Entities made significant concessions regarding The Star’s relationship with

Suncity during the Relevant Period, which included severe errors of judgement with respect

to Salon 95 and Suncity’s service desk operations, those concessions were made belatedly

during closing submissions in the public hearings. By that point, considerable time and

resources had been expended by the Review in investigating these issues. In any event, the

seriousness of the matters pertaining to Suncity and Salon 95 necessitate this Chapter

exploring those issues.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

3

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

Chapter 13.2 The Establishment of Salon 95

13.2.1 The 2017 Rebate Agreement

5. On 30 June 2017, The Star entered into a “Win/Loss Rebate & Exclusive Access

Agreement” with Mr Iek as the junket’s promoter (2017 Rebate Agreement).

9

The

agreement was signed by Mr Chad Barton on behalf of The Star. Clause 6 of the agreement

stipulated that The Star was to provide the promoter “with exclusive access” to a private

gaming salon, namely, “Salon 95 located 1

st

floor of The Darling Hotel, above the Sokyo

bar and restaurant …”. The clause then stated:

Promoter acknowledges and agrees that The Star retains sole operational and

management control of the Exclusive VIP Salon (including the operating hours, who

may access the Exclusive VIP Salon, the conduct of gaming, the operation of the

Cage, provision of food and beverage service and enforcing service standards and

presentation). Promoter may have approved junket representatives present in the

Exclusive VIP Salon (subject to The Star's approval) to assist in customer liaison and

customer service for non-gaming matters. Any operational concerns or issues for

Promoter or its customers will only be raised with The Star's nominated liaison

representative and not with The Star's staff within the Exclusive VIP Salon directly.

(emphasis added)

6. The emphasised passage refers to a “Cage”. That word is undefined but appears to

contemplate a form of cashier’s enclosure located within Salon 95. That is consistent with

the subsequent conduct of Suncity whereby a request was made by junket staff in around

August 2017 to The Star to “set up a cage with two windows and a service counter with

two seats” in the salon.

10

The response of the officers of Star Entertainment in August 2017

is also consistent with the notion that it was at least an open question at that time that there

would be a cage or buy-in desk in the salon.

7. If that is the correct construction, the clause did not make clear how the cage in the salon

would be operated and by whom (i.e. whether by employees of The Star or by junket staff).

However, the clause makes clear that The Star ultimately retained “sole operational and

management control” of the salon. That is emphasised by the following additional

provision of clause 6: “The Star will be responsible for all aspects of the operation of the

Exclusive VIP Salon, at its own cost”.

8. There was little evidence regarding the origins and drafting of the 2017 Rebate Agreement.

However, Mr Micheil Brodie, General Manager of Social Responsibility at Star

Entertainment, gave this evidence:

11

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

4

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

Well, I was – I was aware that in Macau, in particular, a common arrangement was

for junkets, more generally – so not even necessarily Suncity, but junkets more

generally were given a bit more unfettered access to particular gaming areas and

particular salons. If you like, there was a capacity in the licensing structure there for

subletting of licensed areas. And so it was – by about 2018, my recollection is that

that had become a fairly common model in Macau casinos, to have some junkets that

were, you know, effectively embedded as – as sublet operators.

And so we needed to be wary that that's not a model that was authorised in New

South Wales, and we would want to be sure that they weren't tracking towards that

kind of activity.

9. Mr Brodie also said that the “North Asian” model included “a right to operate a cage” by

the junket.

12

10. Under clause 1 of the 2017 Rebate Agreement, a minimum monthly “Non-Negotiable

Turnover of A$50m” was required. That clause also included various rates of rebate

depending upon the type of rebate program. Under clause 5, if the minimum monthly

turnover was not met in certain circumstances The Star at its discretion was permitted to

withdraw the “exclusivity provided in clause 6”.

13

11.

Clause 10(y) of the 2017 Rebate Agreement imposed an obligation on the promoter to

comply, and to ensure to the extent it was within his control that his customers complied,

with “all applicable policies and procedures of The Star relating to the use of equipment

and gaming salons, access to the property… and the conduct of gaming…”. This is

consistent with the recognition in clause 6 that The

Star would retain operational control of

Salon 95.

12. Between 30 June 2017 and January 2018, at Suncity’s request “construction works were

undertaken for the installation of Suncity signage and a service desk”.

14

During that period,

Suncity did not operate from Salon 95.

13.2.2 The layout of Salon 95

13. Salon 95 was located on the Rivers level. “Rivers” was the name provided to one of the

areas of The Star Casino where private gaming rooms were located. There were several

such areas.

15

The Rivers area was located above the Sokyo restaurant at the Darling Hotel.

16

14. Within the Rivers area, there were a number of separate gaming salons

17

of which Salon 95

was one. A “satellite cage” was in operation within the Rivers area (Rivers Satellite Cage).

Generally, within a particular zone of VIP salons there existed a cage or cashier facility that

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

5

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

managed that particular geographic zone.

18

The Rivers Satellite Cage was distinct and

separate from the service desk in Salon 95.

15. The Rivers Satellite Cage was operated by employees of The Star or Star Entertainment.

There is no suggestion of any wrongdoing by casino employees in the Rivers Satellite Cage.

Due to the proximity between Salon 95 and the Rivers Satellite Cage, it was practical for

employees of the junket in Salon 95 to walk from the salon to the Rivers Satellite Cage to

exchange chips or cash.

16. The following image is taken from a diagram of the Rivers area dated 4 September 2017,

enlarging the layout of Salon 95:

19

17. Salon 95 contained three gaming tables. Clause 6 of the 2017 Rebate Agreement stated

that the gaming tables in the salon were to be “exclusively used for playing baccarat”.

20

18.

Salon 95 had a balcony. The balcony was narrow and from the CCTV footage appeared to

contain outdoor furniture

in the form of a table and four chairs on one side and also another

two chairs and side table close to the door connecting the balcony to the internal salon (at

least as at June 2018).

19.

There was only one surveillance camera on the balcony.

21

The camera had a blind spot

beneath it, which would become material to the later use (and potential misuse) of the

balcony by Suncity employees and patrons.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

6

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

20. The salon also included a stand-alone desk referred to throughout the public hearings as the

“service lounge”. The service lounge was a desk in the open area of the salon. It was

apparently staffed by Suncity employees to field questions and provide general assistance

to the patrons in the salon. The Suncity staff wore black suits with white shirts and black

ties.

22

21. The service desk, on the other hand, was a small office located in Salon 95. It was L-shaped

internally. An internal cupboard was located on the shorter side. The desk was located

opposite the longer side. The CCTV footage showed three or four Suncity staff sitting or

standing along the desk and liaising with customers through the window.

22. There was one surveillance camera within the service desk office located in the corner of

the longer side of the office.

23

There was a blind-spot in the room, as there was no or

limited visibility of the wall of the shorter side of the room where the internal cupboard

was located.

Chapter 13.3 Knowingly Misleading Liquor & Gaming NSW

13.3.1 Contemplation of a cage or buy-in desk in Salon 95

23. From the middle of August 2017, there were internal communications between casino

officers, and between casino officers and Suncity representatives, regarding the installation

of a cage or buy-in desk in Salon 95.

24

One email dated 9 August 2017 from a

representative of Suncity to Mr Michael Whytcross, who was the General Manager –

Financial and Commercial at Star Entertainment, stated:

25

Confirmed salon 95 is the proposed location.

Please kindly continue progressing to setup a cage with 2 windows and a service

counter with 2 seaters.

24. The same day, Mr Whytcross forwarded the Suncity email to Mr Damian Quayle, stating:

26

Please see below from Suncity.

Are you able to pass me on to someone who may be able to assist in progressing this

request (i.e. CAD designs).

From there we can look to quantify cost etc and next steps but at face value doesn’t

seem to be too onerous.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

25. In his evidence, Mr Whytcross confirmed he understood “what Suncity wanted” and that

he had passed on those instructions to Mr Quayle “in Sydney so that Sydney could do what

Suncity wanted”.

27

26.

On 10 August 2017, Ms Beata Ofierzynski, a Business Improvement Manager – Gaming

at The Star, sent an email to Mr Whytcross stating:

28

From what I gather in the email trail below, you are looking to add a cage w ith 2

windows and a service counter with 2 seaters in Salon 95?

Will this just be a buy in desk or fully enclosed cage? In regards to the service

counter, will a desk suffice?

In addition, could you please confirm you would like to keep 3 tables in the salon

before we engage our property service team?

27. The same day, Mr Whytcross replied:

29

My preference would be for a buy in desk to minimise cost and disruption rather than

a fully enclosed cage. The service counter will need to be better quality than a desk

we have in storage and would envisage needing locked cupboards also.

28. Mr Whytcross accepted that in his email of 10 August 2017, he was “directing Sydney to

put in a cage”. He said: “Yes. I was following the request from Suncity”.

30

29.

Further emails were exchanged regarding Suncity’s request and the layout of Salon 95. On

15 August 2017, Mr Whytcross sent an email to Mr Marcus Lim, Mr John Chong, and Mr

Saro Mugnaini, stating:

31

Salon 95 in the Rivers (far right as you walk in) has been identified by YM and the

Suncity International Team as the preferred l ocation which would not disrupt Leong

Wa Fong (however turnover from them is still not strong and I feel this needs to be

revisited).

Through Damian Quayle / David Croft I am waiting for some layouts / designs for

the Suncity request which was “setup a cage with 2 windows and a service counter

with 2 seats”. I am expecting this today / tomorrow however the key for them is

being able to set up a computer and have their systems to talk back to Macau.

30. Mr Whytcross was examined upon his email of 15 August 2017. He understood that “cage

was being distinguished from service counter” which was being requested by Suncity staff,

who were requesting both a cage and a service counter.

32

31. Also on 15 August 2017, Ms Ofierzynski sent Mr Whytcross a further email stating:

33

Attached is a drawing for Salon 95 inclusive of new cage/buy in desk in addition to

desk with 2 seats. We had to remove the dining table to accommodate the buy in

desk.

7

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

Please let me know your thoughts....

32. The same day, Mr Whytcross responded stating:

34

From previous experience I would expect Suncity to request further details of the

cage/buy in and separate service desk (i.e. height, drawer space). Is this level of

information available?

To the extent it is not (or may take further time), I would look to share the file you

sent with them as a first step to get feedback.

33. Mr Whytcross confirmed in his evidence that he was referring to his previous experience

at “Crown”, “when they had an exclusive Suncity room”.

35

However, he could not recall

whether Suncity had operated a cage in the “Suncity room” at that casino.

36

34.

The above email chain shows that it was being contemplated that Salon 95

would include

a cage or buy-in desk, and further, such a proposition did not appear to be controversial, at

least to the parties to those emails who were representatives of The Star and Star

Entertainment.

35.

Mr Graeme Stevens, the Regulatory Affairs Manager employed by Star Entertainment at

the time,

37

who was not party to the August 2017 email chain above, accepted that such

conversations were taking place in the business about the cage in Salon 95 and it was the

intention of the business to accommodate Suncity’s request for some sort of buy-in desk in

Salon 95.

38

When shown that correspondence from August 2017, his evidence as to his

state of knowledge was as follows:

39

Q: And all I want to ask you here is, was it – were you aware of such

conversations taking place in the business about the cage in Salon 95 and

its particulars, how it was going to be set up?

A: Yes.

Q: And were you aware of the intention of the business to accommodate what

clearly was a request in the contemplation of Suncity that it would be able

to have some sort of buy-in desk in Salon 95?

A: Yes.

Q: Mr Stevens, y ou told me earlier that you understood that the agreement with

the Sun city junket didn't permit the junket to operate a cage i n Salon 95;

correct?

A: Correct .

Q: So should I understand that these emails - and I appreciate you were not a

party to them, but you would regard these emails as inconsistent with your

understanding of what was permitted under that agreement with Suncity?

8

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

9

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

A: Yes.

…

Q:

But I think your evidence was that

you too were aware, as at August 2017,

that

it was being contemplated by The Star and/or Suncity that there would

be a cage, and it would have some sort of buy-in desk?

A: Yes.

36. Mr Stevens said that his understanding of the 2017 Rebate Agreement was that it did not

permit a cage in Salon 95.

40

That evidence of Mr Stevens’ understanding is inconsistent

with clause 6 of the agreement and, further, the surrounding circumstances by which the

conduct of the staff of Suncity, The Star and Star Entertainment in or around August 2018

indicated that the existence of a cage or buy-in desk was not controversial.

13.3.2 The submission to Liquor & Gaming NSW dated 12 October 2017

37. On 12 October 2017, Mr Stevens made a submission on behalf of The Star to L&GNSW

via an email the subject of which was “Submission COA Lease Terms Approval -The Star

Salon 95 building works”.

41

The covering email (copied to Mr Whytcross) stated:

42

The Star is proposing to make some minor changes to the Junket Operators office

located in The Rivers Gaming Salon 95.

The purpose of these changes is to create a more customer friendly environment by

installing a service desk in the salon and service window in the wall of the junket

Operator’s office.

Due to the nature of these works we believe that the COA Lease terms require owners

consent from ILGA, which I understand to have been delegated to L&G. Please find

attached the formal submission and plans of the work.

If you have any questions or require the submission in another format please let me

know.

38. The attachments to the email included several diagrams and images of the proposed

changes to the service desk in Salon 95.

43

Relevantly, one image showed how the proposed

change was to install a window in the service desk which would face the gaming tables in

the salon.

44

Importantly, the email attached a formal submission also dated 12 October

2017, which relevantly stated:

45

Reason for Submission

To enable the junket operators who use Salon 95 to provide better service for the

junket participants, The Star proposes to open a service window into the wall of the

junket operator’s office. The Authorities approval for this work is required under the

provisions of the Casino Operations Agreement Lease terms. The Star therefore

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

requests the consent in writing from the Authority as required by clause 5.16 of the

Casino Operations Agreement Lease terms.

Details of Changes from Previous Approval

Minor building works to allow the insertion of a service window into t he interior

wall of the Junket Operator office. Installation of a service desk adjacent to the

Junket Operator’s office.

Newly Introduced Feature(s) / Function(s)

The purpose of these changes is to create a more customer friendly environment by

installing a service desk in the salon and service window in the wall

of the Junket

Operator’s office.

39. Mr Stevens accepted that nowhere in the submission was there any reference to the cage or

buy-in desk in Salon 95.

46

Mr Stevens accepted that the submission was misleading and

that he had knowingly misled the regulator in the following evidence:

47

Q: Thank you. You would agree with me, Mr Stevens, that this submission is

misleading?

A: It - it - it doesn't detail that the junket operator was receiving cash from the players

as to facilitate their buy-in - the junket operator was subsequently used to buy in

to their rebate program with us. So - so it's not a fulsome explanation from that

perspective.

Q: It was misleading, wasn't it, Mr Stevens?

A: Correct .

Q: And you knew at the time of sending the submission to the regulator that there was

- it was in the contemplation of there to be a cage and/or a buy-in desk in that

room?

A: Not a contemplation of a cage, but a contemplation that they would be - the players

would be providing funds to the junket operator to - to participate within the junket.

Q: And you knew at the time of sending the submission that you had not included that

additional information in the submission?

A: Yes.

Q: So you knowingly misled the regulator?

A: Yes.

40. This was serious misconduct. The Star Entities accepted that it “constituted grossly

inappropriate and unethical conduct on the part of Mr Stevens”.

48

The Star Entities also

accepted that Mr Stevens was the Regulatory Affairs Manager and therefore the “primary

point of liaison between The Star and The Authority”.

49

The Star Entities accepted that Mr

Stevens should have corrected his submission to L&GNSW, particularly in circumstances

10

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

11

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

where Mr Stevens was aware of the cash transactions taking place at the service desk as at

May 2018.

50

41. The misconduct was aggravated by the two facts that:

first, Mr Stevens was the Regulatory Affairs Manager and thus had an important

role in facing and dealing with the regulator on behalf of The Star – as Dr Pitkin

and Ms Lahey said in their evidence, it is “devastating” for the confidence that the

regulator can have in The Star when a senior compliance executive knowingly

misled them;

51

and

secondly, the knowingly misleading conduct was in relation to something as serious

as potential cage operations – something which goes to the very heart of the lawful

gambling for which The Star holds its casino licence.

13.3.3 Further communication with L&GNSW

42. During his initial examination, Mr Stevens referred to a further communication he had with

the regulator regarding the submission for the installation of a window in the service desk.

52

On 21 November 2017, a representative of L&GNSW sent an email to Mr Stevens stating:

53

As mentioned in my voice messages, we require further clarifications in regard to

the “better service” being provided to the junket participants as a result of the

proposed changes for Salon 95. This includes a description of the current service

being provided in Salon 95, and what “better services” will provided once the

proposed structural changes are approved and completed.

43. Mr Stevens responded the same day, stating:

54

To understand what we mean by ‘better services’ let me first explain the service and

operation of a junket.

The junket operator/representative is the person who ‘buys in’ on behalf of the all of

the junket. They are the ones who draw the funds down and purchase rebate chips

for use in the program. When the operator receives the chips they then provide t hose

chips to the players, who will then return them to the junket operator. The operator

is the person who then ‘rolls them over’. This is the e xchange of prem ium chips for

non neg chips at the gaming table. At the completion of the junket it is the operator

who then presents all of the chips back to the casino for redemption. As part of the

above processes the junket operator keeps records of which players have given or

returned chips to them. The players may have provided their own funds to play or be

using the junket operator’s funds. Sometimes the junket operator will share some or

all of the rebate earnt through gaming with the players. The records kept by the

operator enables them to keep track of what players have received chips and

therefore owe funds to

the operator and what chips they

have then

provided back to

the operator.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

12

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

The junket operator will also receive requests for food, air fare, accommodation and tours

etc from the players which may subsequently be relayed to us.

Currently this provision of chips and the return of those chips takes place either at the

gaming table

or in the Junket Operators office. If it

is at

the table then

there is a lack of

privacy for the player, particularly when there are other players present.

When

it

is

in the office, this takes place in

a fairly enclosed space where there may be other

documentation or records on display which the junket operator does not want the players

to see.

By installing

the desk and service window we are creating a more professional

environments for these transactions to occur.

44. The L&GNSW representative responded to Mr Stevens’ email later that day stating:

55

Thank you for your clarification. I note from our phone conversation that Salon 95

is allocated to the Suncity Group, a junket operator. I also note that the proposed

changes are being considered by the Star at the request of the Suncity Group.

45. Mr Stevens was recalled as a witness and was examined in relation to the above

communications. Mr Stevens accepted that his further email to L&GNSW was misleading,

in failing to disclose that it was proposed that cash transactions or cash/chip exchanges

would occur in Salon 95,

56

but he denied knowingly misleading the regulator on this

occasion.

57

46. It is unnecessary to explore the plausibility of this denial. The result of this further

communication was that, for a second time, the regulator was misled as to the nature of the

transactions proposed to occur at the service desk in Salon 95.

58

13.3.4 The Star’s breach of the Casino Operations Agreement

47. A further question arises whether Mr Stevens’ submission dated 12 October 2017 to

L&GNSW constituted a breach by The Star of the Casino Operations Agreement. Under

paragraph 3 of Schedule 3 of the Amended Casino Operations Agreement, The Star as a

contracting party gave the following warranty:

59

(All information true): All information given at any time and every statement made

at any time by the Contracting Party to the Authority or its employees, agents or

consultants in connection with this Agreement and any Transaction Document is and

will be true in any material respect and is and will not by omission or otherwise be

misleading in any material respect.

48. The Star also provided a similar warranty under paragraphs 1(b) and 7(c) of Schedule 1 of

the Amended Compliance Deed.

60

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

13

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

49. The Star Entities accepted that Mr Stevens’ submission of 12 October 2017 to L&GNSW

“sought the Authority’s consent for the purposes of clause 15.16 of the ‘Casino Operations

Agreement Lease Terms’”, and therefore “Mr Stevens’ email and submission constituted

statements made or information given on behalf of The Star in connection with the Casino

Operations Agreement”. The Star Entities conceded that it was open to the Review to find

that The Star breached the warranties under paragraph 3 of Schedule 3 of the Casino

Operations Agreement and under paragraphs 1(b) and 7(c) of Schedule 1 of the Amended

Compliance Deed.

50. Mr Stevens’ misleading communications to the Authority concerning the proposed use of

the service desk in Salon 95 constituted a breach by The Star of its warranty under the

Casino Operations Agreement.

Chapter 13.4 The Unauthorised use of the Service Desk in Salon 95

13.4.1 The commencement of the service desk: mid-April 2018

An important issue is raised regarding the “Suncity Cage”: 12 March 2018

51.

On 12 March 2018, Mr Wallace Liu, Assistant Vice President of VIP International

Operations at The Star, wrote in an email to Mr David Aloi (emphasis added):

61

As Suncity is using salon 95 as junket salon, their manager TK inquire what amount

of cash limit from patrons can they deposit into Suncity Cage without any AML

requirement?

Junket doesn’t want to cause any AML issue, however this is a very import part of

their business.

Can you advise who I can check with if you are not sure. Thank you in advance.

52. It appears that Mr Wallace Liu’s email had followed a meeting and discussion which Mr

Anthony Lui, Senior Vice President of International Marketing at Star Entertainment, had

had with representatives of Suncity around that time.

62

The minutes of Mr Anthony Lui’s

meeting with Suncity showed various requests that the junket had made “prior to their fix

junket room soft opening”, which included requests regarding cash deposit limits under a

sub-heading titled “CAGE” such as “Cash deposit: How much of cash limit they can

receive from patron by law”.

63

53. The same day, Mr Aloi forwarded Mr Wallace Liu’s email to Mr Oliver White and stated

further:

64

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

I would assume Sun City would have an AML program in place prior to setting up a

cash desk in the Rivers salons. Wouldn’t that be one of the requirements for The Star

allowing them to transact on property?

54. The same day, Mr White forwarded Mr Liu and Mr Aloi’s emails to Mr Power and Mr

Stevens stating:

65

Please see the email below.

Have you been consulted at all in relation to this, as this is the first time I have been

circled in.

Aside from reinforcing to the business that this is not a Cage, only a service desk, it

raises an interesting point around what we are willing to permit SunCity to do at their

service desk. I would have thought that they should not be handling cash payments,

but if they are, then of course they will need to be AML/CTF compliant.

Can we get together to discuss this and the best way forward.

Mr White’s advice: 13 March 2018

55. On 13 March 2018, Mr White responded to Mr Aloi and Mr Liu’s queries and wrote in his

email to them:

66

As an initial point, I should point out that Sun City have a service desk in Salon 95

– they do not operate a cage and have no authority to operate a cage. A cage may

only be operated by the casino operator, i.e. The Star Sydney in this instance.

In relation to the activities of the service desk, whilst Sun City’s representatives are

permitted to assist their customers with their service requests, any transactions

involving cash must only take place at The Star Sydney’s cage. Accordingly, if one

of Sun City’s customers wishes to make a cash payment, they must do this at The

Star Sydney’s cage in accordance with The Star Sydney’s applicable policies and

standard operating procedures (which I note means that the individual making the

payment must attend the cage in person to make the payment). Sun City’s service

desk may handle usual junket operator/representative transactions involving chips

only.

On the basis that Sun City’s service desk does not and will not in future handle any

cash transactions, you should not need to worry about AML/CTF requirements

which may apply to Sun City’s operations, as opposed to those of The Star Sydney.

If you become aware that Sun City are handling cash transactions, please let me,

Saro Mugnaini and Micheil Brodie know as soon as possible – please send an email

to me including “Privileged and confidential” in the ti tle and seek my advice on any

incidents, including any details that are known.

56. Mr White’s advice of 13 March 2018 was at odds with the initial understanding of those

involved in the establishment of Salon 95, as shown in the August 2017 email

correspondence considered above. Mr White’s email made it clear that Suncity was not to

operate the service desk as a casino cage, the junket had no authority to operate a cage and

thus no cash transactions could take place at the service desk.

14

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

15

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

57. Mr White’s advice was based upon cash payments only permissibly taking place at “The

Star Sydney’s cage in accordance with The Star Sydney’s applicable policies and standard

operating procedures”. This appears to be the first occasion on which any objection was

taken by The Star or Star Entertainment to the proposed cage in Salon 95. Mr White

correctly recognised the fact that operating a cage may constitute casino operations and

give rise to AML/CTF implications.

58.

The same day, Mr Brodie forwarded Mr White’s email to Mr McWilliams.

67

Mr

McWilliams was responsible for signing off on the ultimate risk assessment (which would

be prepared by Ms Arnott with Mr Brodie’s guidance).

59. It appears that Mr Mugnaini requested a meeting with “TK”, who was a representative of

Suncity, to discuss Mr White’s advice.

68

Suncity push-back after being denied a cage: 28 March 2018

60. On 20 March 2018, a further meeting took place with Suncity at which the message was

communicated: “even with a service desk they cannot do any cash transaction”.

69

In other

words, Mr White’s advice had been communicated to the junket operator.

61. On 28 March 2018, Mr Mugnaini sent the following email to Mr White:

70

Legal Advice Required

I met with Sun City’s rep’s yesterday.

They asked us to review the below decision and see if we allow them to operate as

in Crown which is.

1. Suncity Reps accept cash from their players (same as occurs between junkets and

players today)

2. Suncity will collect KYC (Photo ID)

3. Suncity makes a deposit to Star Cage each 24 hrs with a breakdown of all

transaction copies of ID’s in a list format.

4. Any large transactions ($100K and above) will require additional

KYC such as

required source of funds documentations.

The above approach I would suggest meets our AML/CTF reporting obligations.

62. Mr Mugnaini’s email was in response to Mr White’s email of 13 March 2018 referred to

above. Evidently, Suncity were still pressing to be able to handle cash from patrons.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

63. The same day, Mr White responded to Mr Mugnaini indicating that he would “consider”

the email and “come back” with a response.

71

Mr White gave evidence that he understood

that Mr Mugnaini was asking him to reconsider his advice of 13 March 2018 and whether

there was “a legal way for Suncity to handle cash at the service desk”.

72

64. On 31 March 2018, Mr Mugnaini sent a further email to Mr White stating:

73

bringing you on discussions on the following:

Points 1 & 3.

- Suncity in-house staff now wish to apply for a Junket Rep license without Police

clearance. Police Clearance to be requested and submitted in 2-3 months.

- Cash handling at the service desk. As per my email seeking further advice on this

matter on the 28 march.

65. The same day, Mr White responded to Mr Mugnaini stating:

74

I will respond separately to the email chain re he first point.

On the second point, I have copied Micheil Brodie as this relates to AML/CTF. Until

Micheil has provided clearance, they cannot handle cash at the service desk.

The Star seeks to accommodate Suncity’s renewed request

66. On 6 April 2018, Mr Brodie sent an email to Mr Lim stating:

75

An action that flows from our conversations about what Sun City can do when

operating at the Sydney property is for my team to conduct an AML risk assessment.

The objective is to review the operational structure and determine the suitability of

the risk and control framework for this service.

Could you advise who in your

team can

give

us a detailed picture of the arrangement

with Sun City and

the day to day

flow of activity. I envisage that it will only need an

hour or so of discussion and some review of what we write up for confirmation.

This will let us get a clear and pragmatic picture of the process and set realistic risk

ratings.

67. The same day, Mr Lim responded to Mr Brodie’s email stating:

76

…

Could you send us the full questions prior to the meeting and we can have them

answered and send back to you and we could conduct the call.

There is a real urgency to have this up and running asap as all sun city marketing

collateral states their room is up by 1st april in sydney.

Alvin chau (CEO of sun city) has a direct influence with our partners CTF and FE.

16

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

68. The same day, Mr Brodie responded to Mr Lim stating “Just to be clear the risk assessment

does not need to slow down the implementation of the arrangement”.

77

Mr Brodie was

examined on this email. His evidence was:

78

Q: Was there some haste at this time in getting the risk assessment done?

A: No, I think that's - I think that's a reference to the fact that these - that the

risk assessment we were doing would not impede the work that they planned

to do in terms of providing Suncity access to the room and some of the other

activity around that. But I wouldn't have allowed the conduct of the risk

assessment to be d one anything other than at the pace that it n eeded to be

completed at.

69. Further on 6 April 2018, Mr Lim then emailed Mr Mugnaini and Mr Whytcross (copied to

Mr Hawkins) stating:

79

How can we get the Junket room to be operational as soon as possible?

Alvin Chau will be making a trip to Sydney towards the end of the month.

70. Mr Hawkins responded stating:

80

Let’s set up the call with Michael Brodie and Paul McWilliams when I am in HK.

Is there a project plan around opening of the room? Clear actions and ownership?

71. Mr Whytcross responded to Mr Hawkins stating (emphasis added):

81

…

Following the installation of Suncity equipment the room is operationally ready

however a further concern was raised around cash collection at the service desk

(however I understood this to be addressed following a discussion with Micheil

as per the attached).

Assuming there is no AML concerns from Micheil and that the risk assessment can

be done concurrently I do

not see why implementation cannot occur immediately.

Will coordinate

for a call when you are in HK.

72. Mr Mugnaini responded stating he would “chase for formal approval on the handling and

have a final position by Thursday”,

82

to which Mr Lim responded “Who are we awaiting

for formal approval?”.

83

On 7 April 2018, Mr Mugnaini responded that they were waiting

on approval from Mr White from legal and Mr Brodie from compliance.

84

On 9 April 2018,

Mr Mugnaini sent a further email to Mr Lim stating:

85

Following actions as an outcome of the meeting:

-AML/CTF risk assessment as new product to be conducted.

17

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

18

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

This will provide guidelines for the o peration to ensure we are compliant.

- Controls and recommendations will be issued in writing as a suitable solution. We

should have this by Thursday.

73. The same day, Mr Lim responded: “Let’s get the room operational by Thursday”.

86

74. If that deadline was met, then Salon 95 would have been operational by 12 April 2018. It

is not clear precisely when the room began operating, but it is likely that it was around the

middle of April 2018 and certainly by 18 April 2018 given CCTV footage produced from

Salon 95.

75. The email correspondence shows that there was pressure being applied by Mr Lim to have

the salon operating as soon as possible, including by reference to Mr Chau (a major source

of business) and his connections to Star Entertainment’s joint venture partners Chow Tai

Fook and Far East Consortium. The evidence suggests that the risk assessment was not

rushed to allow the room to open, but Salon 95 proceeded to open before the risk

assessment was completed.

76. The Star Entities conceded that it was not appropriate for the service desk to operate before

Mr McWilliams had provided his approval.

87

Ms Arnott’s recommendations of 13 and 16 April 2018

77. Ms Arnott had principal carriage for preparing the risk assessment.

88

Her evidence was that

in early April 2018 Mr Brodie had requested that she perform such an assessment.

89

The

assessment was to identify “money laundering and other risks that may lead to non-

compliance with the Casino Control Act”.

90

The first draft was prepared by 11 April

2018.

91

78.

On 12 April 2018, Ms Arnott had circulated a draft risk assessment to Mr Mugnaini and

Mr Brodie copying in Mr McWilliams.

92

The same day, Mr Mugnaini forwarded a copy

of the draft risk assessment to Mr Hawkins, Mr Lim and Mr Whytcross, and stated in the

email “For today’s meeting”.

93

On 12 April 2018 Mr Mugnaini also forwarded Ms Arnott’s

email to Ms Angela Huang of Star Entertainment asking her some questions about the

“controls” and to follow up with Ms Arnott.

94

It appears that two chains of emails then

emerged from Mr Mugnaini forwarding Ms Arnott’s email twice. This led to two important

responses from Ms Arnott clarifying the way her controls were to be understood.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

19

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

79. On 13 April 2018, Mr Whytcross sent an email to Ms Arnott in which he stated (emphasis

in original):

95

As discussed just now, understand the risk assessment document was for internal

purposes only.

As we ran through, and in terms of feeding this information back with Suncity (for

reference Marcus is due to speak with Alvin Chau this evening) would recommend

we proceed on following approach:

• Current identity check process is to continue unchanged;

• Cash received at the Suncity Service desk to be deposited into The Star

cage on a daily basis – Separately we can ma nage internally over the initial

period to determine if this is reasonable / p ractical;

• Customers can not receive cash in exchange for chips in the same

transaction;

•

Cash received at the Suncity Service desk cannot be used to settle with

patrons. Any settlement must be at the cage.

80. Mr Arnott explained that these were not controls proposed by Mr Whytcross, but rather she

believed that he was “clarifying the information that would have been communicated to

him around controls, making sure he understood it appropriately before relaying it to

Suncity”.

96

81.

Mr Brodie stated in his evidence that this was a “kind of stage summary” of the controls.

97

He explained that while the controls were limited, this was because putting “some things

in place right away and then once we’d completed the process of the risk assessment, then

we were able to determine a more holistic set of controls”.

98

82.

Ms Arnott responded to Mr Whytcross’ email the same day, stating:

99

I have discussed with Micheil and we are happy to proceed with this communication

to Sun with a minor amendment to point 2. Can this please read “Cash received at

the Suncity Service Desk to be deposited into The Star cage at least on a daily basis.”

If they receive an very large deposit or a significant number of small deposits it

would be good if they could clear that cash more quickly.

The reasonably practicable control here is to avoid the situation where a patron

demands that the Sun staff provide cash that is being held at the service desk. It could

be very difficult for Suncity staff to refuse if a patron is aware that cash is held for

long periods. I agree that testing the adequacy of this control via surveillance and the

cage in the first instance is the right approach.

83. Mr Brodie confirmed that this was “the first round of controls that were communicated to

Suncity”.

100

Ms Arnott said that requiring Suncity to deposit the cash received at The Star

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

20

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

cage “was an effective control for stopping them from acting as a cage, the idea that the

money flows through to The Star cage and isn't held for a long period of time”.

101

84. On 13 April 2018, Ms Huang and Ms Arnott exchanged several emails. Late on 13 April

2018, Ms Huang sent an email to Ms Arnott stating:

102

Can I ask if some of the controls are new? I don't have access to intranet from home

so not sure if they are.

Also just having a quick glance at the document, I think we are basically saying to

Suncity that players must be added prior to the junket with indicated fund on the

front money summary before they can be

disbursed with chips. Any winnings must

be paid out to

them once partials have been done to

indicate t

hat th

ey money

disbursed is the winnings from the program.

Basically ensuring that we have

visibility of all players, player action and meeting

AML/CTF laws.

85. On 16 April 2018, Ms Arnott responded to Ms Huang’s email stating:

103

The controls are mostly new, the first one relating to the collection of ID from SGR staff is

existing (I believe) but the rest will be new.

We are basically asking for the following:

• That Sun City staff do not exchange cash for chips (or vice versa)

• All cash be taken to the cage as soon as practicable after it is received

• Cash received cannot be given to patrons as winnings. It must be banked

• Settlements and partial settlements must occur at the cage and the Junket

rep can distribute the funds to relevant patron.

We are also recommending a position that will prevent patrons being added to

junkets once they have started (so no month long junkets where people are added

and removed as they arrive and leave) but this is now being discussed separately.

Just for your info – I spoke to Michael Whytcross on Friday night because Marcus

was meeting with the Suncity reps. I will forward that email chain to you as it may

be helpful.

86. Mr Brodie explained that Ms Arnott’s communications above to Ms Huang were to ensure

the “first line of defence” were also aware of the controls.

104

Ms Arnott explained the

importance of each bullet point in her evidence:

105

“That Sun City staff do not exchange cash for chips (or vice versa)” – according to

Ms Arnott “that would be offering a designated service for the exchange of cash

for chips”;

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

“All cash be taken to the cage as soon as practicable after it is received” – according

to Ms Arnott this was because “the control should be that the money is banked with

the cage so it can be allocated to the junket”;

“Cash received cannot be given to patrons as winnings. It must be banked” –

according to Ms Arnott “that's the reverse of the original designated service, which

is that you - they should not be exchanging chips for cash. So the money had to all

flow to the cage and then back out again (indistinct) winnings”; and

“Settlements and partial settlements must occur at the cage and the Junket rep can

distribute the funds to relevant patron” – according to Ms Arnott “that is a casino

cage function”.

87. As at 18 April 2018, the risk assessment was not yet finalised and Mr Brodie was still

liaising with Ms Arnott regarding its content.

106

This is important because concerning

CCTV footage from Salon 95 had begun to emerge from at least 18 April 2018. It appears

that only a “summary” of Ms Arnott’s controls had been communicated to Suncity at this

point.

88. In any event those controls, which had been considered by Mr Brodie, acted as a halfway

house between, on the one hand, seeking to prevent the service desk from operating as a

casino cage, while, on the other hand, permitting the junket to handle cash at the service

desk.

89. It appears that by 18 April 2018, The Star had acceded to Suncity’s request to engage in

cash transactions (at least of some kind) at the service desk in Salon 95. In doing so, The

Star did not follow the advice from Mr White’s email of 13 March 2018. At a minimum,

The Star was courting significant risks by taking that course. It should not have done so.

13.4.2 Large cash payments at the service desk: 18 April 2018

First piece of CCTV footage of 18 April 2018 (large sums of cash)

90.

On 18 April 2018, footage of cash transactions at the service desk of Salon 95 was captured

on CCTV.

91.

A truncated

version of that footage was played during the examination of Mr Angus

Buchanan.

107

The footage depicted a black bag with a blue trim being collected from the

balcony of Salon 95 and taken into the service desk through the side door by a man in a

21

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

22

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

black suit. The bag was opened in the service desk room and many bundles of cash (holding

a collection of $50 notes in each) were removed from the bag. The money was then counted

through a money counter and piled on the service desk, and then placed in a drawer

underneath the desk. The footage then depicted a person who was not in the room, handling

some of the money that had been placed on the desk.

92.

Mr Buchanan, after being shown the footage, agreed that the footage was “completely

contrary” to any instructions that Mr White had given in his email of 13 March 2018.

108

Mr Buchanan also accepted that it appeared that Suncity was engaging in “very similar

activity to a cage”.

109

93. Ms Arnott, who was also shown the footage during her examination,

110

gave evidence that

the footage concerned her on the basis that it showed “large sums of cash that’s coming

into the room that’s not associated with a customer directly, or at least not that we can

see”.

111

The footage was therefore concerning to her due to the volumes of the cash being

depicted.

94. However, Ms Arnott gave evidence the footage did not “necessarily” show non-compliance

with the controls she recommended.

112

This is likely to be because her controls envisaged

that cash would be deposited at the service desk.

Second piece of CCTV footage of 18 April 2018 (further large sums of cash)

95. Some further truncated footage from 18 April 2018, depicting a different incident, showed

a man in a black suit removing a bag from the balcony of Salon 95 and taking it into the

salon. The bag was taken into the service desk room. Numerous bundles of cash were then

removed from the bag.

113

Mr Buchanan agreed that the second piece of footage from 18

April 2018 depicted “very large amounts of cash being taken into the enclosed rooms in

Salon 95”.

114

96. This further footage was shown to Ms Arnott during her examination. Ms Arnott gave

evidence that the footage concerned her for similar reasons to the first footage of 18 April

2018.

115

Again, the second piece of footage of 18 April 2018 did not directly breach Ms

Arnott’s recommended controls. Rather, this was a further instance of large sums of money

being handled in a concerning manner by non-casino staff. This was also contrary to Mr

White’s advice of 13 March 2018.

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

13.4.3 The completed risk assessment: 27 April 2018

97. On 27 April 2018, Mr McWilliams signed off on Ms Arnott’s risk assessment for the

service desk in Salon 95.

116

The following risks were identified:

117

When considered in respect of both AML law and NSW Casino law the risks relating

to the Sun City service desk activities are:

- the accidental provision of a designated service by Sun City without

appropriate AUSTRAC registration or structures in place; and

- that operations of the casino could be (or be perceived to be) conducted by

a person other than the casino operator which is prohibited under the Casino

Control Act; and

- the operation of ‘super junkets’ where unrelated parties are added to an

overarching junket agreement rather than each group of people being treated

as an individual junket.

98. Those risks were ones with serious consequences. In particular, the first risk envisaged an

entity operating within the casino performing a designated service while not being

compliant with the AML/CTF Act, including the obligation to have an AML/CTF program.

The second risk envisaged the operation of an unlicensed casino within The Star Casino in

Sydney. That risk was a real and material one in circumstances where Suncity employees

were handling cash and chips at the service desk while holding no licence to do so.

99. The “controls” that were proposed by Ms Arnott and approved by Mr McWilliams

included:

118

- Players may not be accepted in to junkets until they have undergone

appropriate identity checks by an employee of The Star Entertainment

Group. The employee will sight an appropriate identity document (such as

a passport) and record details, including the customers address, in the CMS

prior to guests being signed onto Suncity junket programs. These identity

checks will meet with The Star Entertainment Group’s requirements for

KYC under the AML/CTF Program.

- Cash accepted from players must not be retained at the Sun City Service

Desk or be provided to patrons as cash dispersals. Cash received must be

deposited into the Sun City

Front Money account (or exchanged for a

chip

purchase voucher) at the Star cage as soon as practicable after it has been

received from the junket participant.

-

Customers will not be able to provide cash and receive chips in

the same

transaction.

-

The junket operator may not provide chips to players that have not been

received from the casino cage in exchange for cash or as a result

as of a CCF

draw down. If the Sun City

Service Desk

draws down an excess of chips

from the cage, these may be provided to the patrons. The provision of chips

Review of The Star Pty Ltd, Inquiry under sections 143 and 143A of the Casino Control Act 1992 (NSW)

23

CHAPTER 13 | THE STAR’S DEALINGS WITH SUNCITY SINCE 2016

will not be performed in the same transaction or receipted together with the

acceptance of cash.

- Upon settlement (or partial settlement) of a junket, staff from the Sun City

Service Desk must exchange chips for cash at The Star cage and then

disperse cash to players. Sun City may not draw down (or retain) an excess

of cash to provide directly to players at other times.

100. These controls appear to have built upon the “summary” Ms Arnott had provided in her

emails of 13 April 2018 and which appear to have been communicated to Suncity. The risk

assessment concluded that it was “possible for the Sun City Service desk to operate in a

compliant fashion without significant compromise to the customer experience”.

119

In

circumstances where the risk assessment facilitated cash transactions in Salon 95, and was

contrary to Mr White’s advice of 13 March 2018, it is difficult to understand the basis and

reasoning of the risk assessment.

13.4.4 Chips for cash exchanges at the service desk: 8 May 2018

The Star’s surveillance staff start sounding the alarms

101. From early May 2018 onwards, the level of concerning activity in Salon 95 escalated. On

3 May 2018, Ms Arnott sent an email to Mr Wayne Millett and Mr Brodie stating:

120

Surveillance say that the suncity service desk is behind a little window and that

patrons do not have access to the area. They are seeing Sun staff bring in cardboard

boxes (that look like they were originally photocopy paper boxes) containing cash to

the service desk area on a semi regular basis. I have asked to find out what the source