EXPLANATION OF PROPOSED INCOME TAX TREATY

BETWEEN THE UNITED STATES AND JAPAN

Scheduled for a Hearing

Before the

COMMITTEE ON FOREIGN RELATIONS

UNITED STATES SENATE

On October 29, 2015

____________

Prepared by the Staff

of the

JOINT COMMITTEE ON TAXATION

October 28, 2015

JCX-136-15

i

CONENTS

Page

INTRODUCTION .......................................................................................................................... 1

I. SUMMARY ......................................................................................................................... 2

II. OVERVIEW OF U.S. TAXATION OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE AND

INVESTMENT AND U.S. TAX TREATIES ..................................................................... 4

A. U.S. Tax Rules .............................................................................................................. 4

B. U.S. Tax Treaties .......................................................................................................... 7

III. OVERVIEW OF JAPANESE TAX LAW .......................................................................... 9

A. National Income Taxes ................................................................................................. 9

B. International Aspects of Domestic Japanese Tax Law ............................................... 12

C. Other Taxes ................................................................................................................. 15

IV. ECONOMIC OVERVIEW ................................................................................................ 16

A. Introduction ................................................................................................................. 16

B. Overview of Economic Activity Between the United States and Japan ..................... 18

V. EXPLANATION OF PROPOSED PROTOCOL .............................................................. 26

Article I ............................................................................................................................. 26

Article II ............................................................................................................................ 26

Article III .......................................................................................................................... 26

Article IV .......................................................................................................................... 27

Article V............................................................................................................................ 29

Article VI .......................................................................................................................... 30

Article VII ......................................................................................................................... 31

Article VIII ........................................................................................................................ 31

Article IX .......................................................................................................................... 31

Article X............................................................................................................................ 33

Article XI .......................................................................................................................... 34

Article XII ......................................................................................................................... 37

Article XIII ........................................................................................................................ 40

Article XIV ....................................................................................................................... 43

Article XV ......................................................................................................................... 43

VI. U.S. MODEL TREATY AS A REFLECTION OF U.S. TAX POLICY .......................... 45

A. Mandatory Arbitration ................................................................................................ 45

B. Mutual Collection Assistance Under Present Law ..................................................... 50

1

INTRODUCTION

This pamphlet,

1

prepared by the staff of the Joint Committee on Taxation, describes the

protocol to amend the income tax treaty and protocol currently in force between the United

States and Japan (the “proposed protocol”). The proposed protocol was signed on January 24,

2013, and, when ratified, will amend the income tax treaty and protocol between the United

States and Japan (respectively, the “existing treaty” and “2003 Protocol”) signed on November 6,

2003. The Senate Committee on Foreign Relations has scheduled a public hearing on the

proposed protocol for October 29, 2015.

2

Part I of the pamphlet provides a summary of the proposed protocol. Part II provides a

brief overview of U.S. tax laws relating to international trade and investment and of U.S. income

tax treaties in general. Part III provides a brief overview of the tax laws of Japan. Part IV

provides a discussion of investment and trade flows between the United States and Japan. Part V

explains, in order, each article of the proposed protocol. Part VI describes issues that members

of the Committee on Foreign Relations may wish to consider in their deliberations over the

proposed protocol.

1

This document may be cited as follows: Joint Committee on Taxation, Explanation of Proposed Income

Tax Treaty Between the United States and Japan (JCX-136-15), October 28, 2015. References to “the Code” or

“sections” are to the U.S. Internal Revenue Code of 1986, as amended. This document is available on the internet at

http://www.jct.gov.

2

For a copy of the proposed protocol, see Senate Treaty Doc. 114-1.

2

I. SUMMARY

The principal purposes of the proposed protocol are to reduce or eliminate double

taxation of income earned by residents of each country from sources within the other country,

and to prevent avoidance or evasion of the taxes of the two countries. The proposed protocol

also is intended to promote closer economic cooperation between the two countries and to

eliminate possible barriers to trade and investment caused by overlapping taxing jurisdictions of

the two countries. As in other U.S. tax treaties, these objectives principally are achieved through

each country’s agreement to limit, in certain specified situations, its right to tax income derived

from its territory by residents of the other country.

Article II provides that companies that are resident in both Japan and the United States

(dual resident companies) will not be considered resident of either jurisdiction for purposes of

the treaty. As a result, the treaty benefits available to such companies are limited to those that

are available to nonresidents.

In Article III, the proposed protocol reduces the ownership threshold for elimination of

source-country taxation of dividends received by a resident of one treaty jurisdiction from

company resident in the other treaty country to at least 50 percent of the voting stock of the

company paying the dividends. Article III also reduces the required holding period for

elimination of source-country taxation on such dividends to the six-month period ending on the

date on which entitlement to the dividends is determined.

Article IV replaces Article 11 of the existing treaty, regarding taxation of cross-border

interest payments. Under the revised rules, interest arising in one treaty jurisdiction and paid to a

beneficial owner who is resident in the other treaty jurisdiction is generally subject to tax only in

the residence country. Anti-abuse provisions are provided for contingent interest payments and

for certain payments with respect to ownership in entities used for securitization of real estate

mortgages.

Article V revises the definition of real property in Article 13 of the existing treaty to

conform more closely to the U.S. Model treaty.

Article VII repeals Article 20 of the existing treaty, which provides certain benefits to

researchers and teachers from one jurisdiction when they are temporarily present in the other

jurisdiction, consistent with modern treaty policy of both the United States and Japan. A

conforming change is made by Article I to paragraph 5 of Article 1 of the existing treaty.

Article IX revises the rules regarding foreign tax credits to conform to changes in

Japanese statutory rules for relief from double taxation. The changes reflect the recent adoption

of a participation exemption system in Japan.

Article X revises the nondiscrimination rules of Article 24 of the existing treaty to reflect

the changes to Article 11, as summarized above.

Article XI amends the mutual agreement procedure, which presently allows arbitration at

the discretion of the competent authorities, by prescribing mandatory and binding arbitration in

cases in which the competent authorities are unable to reach agreement. The article prescribes

3

standards similar but not identical to those found in recent treaties with Belgium, France,

Germany, and Canada. Inclusion of a requirement for mandatory arbitration departs from the

U.S. Model treaty.

3

The proposal also departs from the U.S. Model rules regarding mutual

agreement procedures generally, in that it does not require that the presenter of the case have

filed a return with each of the two jurisdictions and allows the taxpayer who presents a case to

submit a position paper directly to the arbitration panel. It also may expedite the schedule on

which a taxpayer who seeks a bilateral advanced pricing agreement may contest a proposed

adjustment that is related to the subject of the pending request for a pricing agreement, thus

compelling arbitration if the competent authorities do not reach agreement on the bilateral

advanced pricing agreement.

The proposed protocol revises the administrative assistance provisions of the existing

treaty in two ways. First, Article XII of the proposed protocol modernizes the exchange of

information provisions of Article 26 to conform to recent standards of transparency. Second,

Article XIII expands the mutual collection assistance available under Article 27. With respect to

the latter, the changes to the scope of collection assistance are similar to those in only five other

tax treaties.

Article XIV amends the 2003 protocol to conform to the above changes and to add

paragraphs needed to implement the mandatory arbitration and the mutual collection assistance

provisions. Other changes are also made in the proposed protocol to correct language errors in

the existing treaty and to update references to relevant domestic laws named in the existing

treaty.

The rules of the proposed protocol generally are similar to rules of recent U.S. income tax

treaties, the U.S. Model treaty, and the 2014 Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital of

the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (the “OECD Model treaty”).

4

The proposed protocol does, though, include certain substantive deviations from these treaties

and models. Significant deviations are noted throughout the explanation of the proposed

protocol in Part V of this pamphlet and are discussed in Part VI.

3

The full text of the Model United States Income Tax Convention, with the accompanying Technical

Explanation, published November 15, 2006, is available at http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-

policy/treaties/Pages/international.aspx.

4

OECD (2014), Model Tax Convention on Income and on Capital: Condensed Version 2014, OECD

Publishing. http://dx.doi.org/10.1787/mtc_cond-2014-en

. The OECD Model treaty is a consensus document that is

intended to settle issues of double taxation as well as to ensure that inappropriate double nontaxation results. The

multinational organization was first established in 1961 by the United States, Canada and 18 European countries,

dedicated to global development, and has since expanded to 34 members.

4

II. OVERVIEW OF U.S. TAXATION OF INTERNATIONAL TRADE

AND INVESTMENT AND U.S. TAX TREATIES

This overview describes certain U.S. tax rules relating to foreign income and foreign

persons that apply in the absence of a U.S. tax treaty. This overview also discusses the general

objectives of U.S. tax treaties and describes some of the modifications to U.S. tax rules made by

treaties.

A. U.S. Tax Rules

5

The United States has a worldwide tax system under which U.S. citizens, resident

individuals, and domestic corporations generally are taxed on all income, whether derived in the

United States or abroad. The United States does not impose an income tax on foreign

corporations on income earned from foreign operations, whether or not some or all its

shareholders are U.S. persons. Income earned by a domestic parent corporation from foreign

operations conducted by foreign corporate subsidiaries generally is subject to U.S. tax when the

income is distributed as a dividend to the domestic parent corporation. Until that repatriation,

the U.S. tax on the income generally is deferred. U.S. shareholders of foreign corporations are

taxed by the United States when the foreign corporation distributes its earnings as dividends or

when a U.S. shareholder sells it stock at a gain. Thus, the U.S. tax on foreign earnings of foreign

corporations is “deferred” until distributed to a U.S. shareholder or a U.S. shareholder recognizes

gain on its stock.

However, certain anti-deferral regimes may cause the domestic parent corporation to be

taxed on a current basis in the United States on certain categories of passive or highly mobile

income earned by its foreign corporate subsidiaries, regardless of whether the income has been

distributed as a dividend to the domestic parent corporation. The main anti-deferral regimes in

this context are the CFC rules of subpart F

6

and the PFIC rules.

7

A foreign tax credit generally is

available to offset, in whole or in part, the U.S. tax owed on foreign-source income, whether the

income is earned directly by the domestic corporation, repatriated as an actual dividend, or

included in the domestic parent corporation’s income under one of the anti-deferral regimes.

8

With respect to nonresident alien individuals or foreign corporations, the U.S.-source

fixed or determinable annual or periodical income (including, for example, interest, dividends,

rents, royalties, salaries, and annuities) that is not effectively connected with the conduct of a

U.S. trade or business is subject to U.S. tax at a rate of 30 percent of the gross amount paid.

Certain insurance premiums earned by a nonresident alien individual or foreign corporation are

5

The U.S. tax rules are codified in Title 26, of the United States Code, referred to as the Internal Revenue

Code of 1986, as amended (“IRC”). Unless otherwise stated, all section references in this document are to the IRC.

6

Secs. 951-964.

7

Secs. 1291-1298.

8

Secs. 901, 902, 960, 1293(f).

5

subject to U.S. tax at a rate of one or four percent of the premiums. These taxes generally are

collected through withholding. Certain payments of U.S.-source income paid to foreign financial

institutions and other foreign entities also are subject to withholding tax at a rate of 30 percent

unless the foreign financial institution or foreign entity is compliant with specific reporting

requirements.

Specific statutory exemptions from the 30-percent withholding tax are provided. For

example, certain original issue discount and certain interest on deposits with banks or savings

institutions are exempt from the 30-percent withholding tax. An exemption also is provided for

certain interest paid on portfolio debt obligations. In addition, income of a foreign government

or international organization from investments in U.S. securities is exempt from U.S. tax.

U.S.-source capital gains of a nonresident alien individual or a foreign corporation that

are not effectively connected with a U.S. trade or business generally are exempt from U.S. tax,

with two principal exceptions: (1) gains realized by a nonresident alien individual who is present

in the United States for at least 183 days during the taxable year, and (2) certain gains from the

disposition of interests in U.S. real property.

Rules are provided for the determination of the source of income. For example, interest

and dividends paid by a U.S. resident or by a U.S. corporation generally are considered U.S.-

source income. Conversely, dividends and interest paid by a foreign corporation generally are

treated as foreign-source income. Notwithstanding this general rule that dividends and interest

are sourced based upon the residence of the taxpayer making such a payment, special rules may

apply in limited circumstances to treat as foreign source certain amounts paid by a U.S. resident

taxpayer and treat as U.S. source certain amounts paid by a foreign resident taxpayer.

9

Rents and

royalties paid for the use of property in the United States are considered U.S.-source income.

Because the United States taxes U.S. citizens, residents, and corporations on their

worldwide income, double taxation of income can arise when income earned abroad by a U.S.

person is taxed by the country in which the income is earned and also by the United States. The

United States seeks to mitigate this double taxation generally by allowing U.S. persons to credit

foreign income taxes paid against the U.S. tax imposed on their foreign-source income. A

fundamental premise of the foreign tax credit is that it may not offset the U.S. tax liability on

U.S.-source income. Therefore, the foreign tax credit provisions contain a limitation that ensures

that the foreign tax credit offsets only the U.S. tax on foreign-source income. The foreign tax

credit limitation generally is computed on a worldwide basis (as opposed to a “per-country”

basis). The limitation is applied separately for certain classifications of income. In addition, a

special limitation applies to credits for foreign oil and gas taxes.

9

For example, certain payments of interest by a foreign bank branch or foreign thrift branch of a domestic

corporation or partnership as foreign source. Similarly, several rules apply to treat as U.S. source certain payments

made by a foreign resident. For example, certain interest paid by a foreign corporation that is engaged in a U.S.

trade or business at any time during its taxable year or has income deemed effectively connected with a U.S. trade or

business during such year is treated as U.S. source.

6

For foreign tax credit purposes, a U.S. corporation that owns 10 percent or more of the

voting stock of a foreign corporation and receives a dividend from the foreign corporation (or is

otherwise required to include in its income earnings of the foreign corporation) is deemed to

have paid a portion of the foreign income taxes paid by the foreign corporation on its

accumulated earnings. The taxes deemed paid by the U.S. corporation are included in its total

foreign taxes paid and its foreign tax credit limitation calculations for the year in which the

dividend is received.

7

B. U.S. Tax Treaties

The traditional objectives of U.S. tax treaties have been the avoidance of international

double taxation and the prevention of tax avoidance and evasion. Another related objective of

U.S. tax treaties is the removal of the barriers to trade, capital flows, and commercial travel that

may be caused by overlapping tax jurisdictions and by the burdens of complying with the tax

laws of a jurisdiction when a person’s contacts with, and income derived from, that jurisdiction

are minimal. The U.S. Model treaty, published in 2006 with an accompanying Technical

Explanation by the Department of Treasury, reflects the most recent comprehensive statement of

U.S. policy with respect to tax treaties.

10

To a large extent, the treaty provisions designed to

carry out these objectives supplement U.S. tax law provisions having the same objectives; treaty

provisions modify the generally applicable statutory rules with provisions that take into account

the particular tax system of the treaty partner.

The objective of limiting double taxation generally is accomplished in treaties through

the agreement of each country to limit, in specified situations, its right to tax income earned

within its territory by residents of the other country. For the most part, the various rate

reductions and exemptions agreed to by the country in which income is derived (the “source

country”) in treaties are premised on the assumption that the country of residence of the taxpayer

deriving the income (the “residence country”) may tax the income at levels comparable to those

imposed by the source country on its residents. Treaties also provide for the elimination of

double taxation by requiring the residence country to allow a credit for taxes that the source

country retains the right to impose under the treaty. In addition, in the case of certain types of

income, treaties may provide for exemption by the residence country of income taxed by the

source country.

Treaties define the term “resident” so that an individual or corporation generally will not

be subject to tax as a resident by both of the countries. Treaties generally provide that neither

country may tax business income derived by residents of the other country unless the business

activities in the taxing jurisdiction are substantial enough to constitute a permanent establishment

or fixed base in that jurisdiction. Treaties also contain commercial visitation exemptions under

which individual residents of one country performing personal services in the other are not

required to pay tax in that other country unless their contacts exceed certain specified minimums

(for example, presence for a set number of days or earnings in excess of a specified amount).

Treaties address the taxation of passive income such as dividends, interest, and royalties from

sources within one country derived by residents of the other country either by providing that the

income is taxed only in the recipient’s country of residence or by reducing the rate of the source

country’s withholding tax imposed on the income. In this regard, the United States agrees in its

tax treaties to reduce its 30-percent withholding tax (or, in the case of some income, to eliminate

10

The U.S. Model treaty has been updated periodically. For a comparison of the U.S. Model treaty with

its 1996 predecessor, see Joint Committee on Taxation, Comparison of the United States Model Income Tax

Convention of September 20, 1996 with the United States Model Income Tax Convention of November 15, 2006

(JCX-27-07), May 8, 2007. Several revisions and additions to the U.S. Model treaty were announced on May 20,

2015, for public comment, but a complete revised model has not been published. The proposals are available at

http://www.treasury.gov/resource-center/tax-policy/treaties/Pages/international.aspx

.

8

it entirely) in return for reciprocal treatment by its treaty partner. In particular, under the U.S.

Model treaty and many U.S. tax treaties, source-country taxation of most payments of interest

and royalties is eliminated, and, although not provided for in the U.S. Model treaty, many recent

U.S. treaties forbid the source country from imposing withholding tax on dividends paid by an

80-percent owned subsidiary to a parent corporation organized in the other treaty country.

In its treaties, the United States, as a matter of policy, generally retains the right to tax its

citizens and residents on their worldwide income as if the treaty had not come into effect. The

United States also provides in its treaties that it allows a credit against U.S. tax for income taxes

paid to the treaty partners, subject to the various limitations of U.S. law.

The objective of preventing tax avoidance and evasion generally is accomplished in

treaties by the agreement of each country to exchange tax-related information. Treaties generally

provide for the exchange of information between the tax authorities of the two countries when

the information is necessary for carrying out provisions of the treaty or of their domestic tax

laws. The obligation to exchange information under the treaties typically does not require either

country to carry out measures contrary to its laws or administrative practices or to supply

information that is not obtainable under its laws or in the normal course of its administration or

that would reveal trade secrets or other information the disclosure of which would be contrary to

public policy. Several recent treaties and protocols provide that, notwithstanding the general

treaty principle that treaty countries are not required to take any actions at variance with their

domestic laws, a treaty country may not refuse to provide information requested by the other

treaty country simply because the requested information is maintained by a financial institution,

nominee, or person acting in an agency or fiduciary capacity. This provision thus explicitly

overrides bank secrecy rules of the requested treaty country. The Internal Revenue Service

(“IRS”) and the treaty partner’s tax authorities also can request specific tax information from a

treaty partner. These requests can include information to be used in criminal tax investigations

or prosecutions.

Administrative cooperation between countries is enhanced further under treaties by the

inclusion of a “competent authority” mechanism to resolve double taxation problems arising in

individual cases and, more generally, to facilitate consultation between tax officials of the two

governments. Several recent treaties also provide for mandatory arbitration of disputes that the

competent authorities are unable to resolve by mutual agreement.

Treaties generally provide rules to ensure that nationals and residents of a Contracting

State may not be subject, directly or indirectly, to discriminatory taxation in the other

Contracting State. Under the nondiscrimination rules, neither country may subject nationals or

residents of the other country to taxation that is more burdensome than the tax it imposes on its

own nationals or enterprises in the same circumstances.

At times, residents of countries that do not have income tax treaties with the United

States attempt to use a treaty between the United States and another country to avoid U.S. tax.

To prevent third-country residents from obtaining treaty benefits intended for treaty country

residents only, treaties generally contain “anti-treaty shopping” provisions designed to limit

treaty benefits to bona fide residents of either of the two countries.

9

III. OVERVIEW OF JAPANESE TAX LAW

11

A. National Income Taxes

Overview

Japan is a parliamentary government with a constitutional monarchy, operating under a

constitution that became effective in 1947. It is a member of many of the same international

organizations as the United States, including those with regional significance, the Asia-Pacific

Economic Cooperation Forum (APEC) and the Association of Southeast Asia Nations (ASEAN)

Regional Forum. Japan has participated in the negotiations to form a Trans-Pacific Partnership

trade agreement since 2013.

12

The central government is organized through a bicameral

legislative body, the Diet, which selects the prime minister. The country is divided into 47

administrative units or prefectures.

Japanese law treats individual income taxes and corporation income taxes separately,

under the Income Tax Law and the Corporation Tax Law, respectively. The Special Tax

Measures Law may modify or supplement the general principles in these basic laws. The

Japanese income tax system and general rules are broadly similar to the U.S. income tax system

and reflect many of the same complexities, including rules for defining the tax base, deductions,

depreciation, credits, and timing. Many types of income, including interest, dividends, and

employment income (for individuals) are subject to withholding at the source.

Individuals

For individuals resident in Japan, income tax is assessed primarily on the basis of an

individual’s combined income. Income tax for retirement income (a lump-sum payment at

retirement) and timber income is calculated separately. Certain income is subject to special rules

and may be separately taxed under the Special Tax Measures Law. The rate structure for

national income tax is progressive and extends from five percent for taxable income under 1,950

million yen (approximately $16,300) to 45 percent for taxable income over 40 million yen

11

The information in this section relates to Japanese law and is based on the Joint Committee staff’s

review of secondary sources. See Bloomberg BNA, Global Tax Guide, Asia/Pacific, Japan, July 23, 2015, available

online at https://www.bloomberglaw.com/document/X2MJF2H8

; Takagi, 7200 T.M., Business Operations in Japan,

2013; R. Saw, Japan - Corporate Taxation, Country Surveys IBFD, January 2, 2015; R. Saw, Japan - Individual

Taxation, Country Surveys IBFD, January 2, 2015; E. N. Rose, Japan - Corporate Taxation, Country Analyses

IBFD, January 1, 2015; E. N. Rose, Japan - Individual Taxation, Country Analyses IBFD, January 1, 2015. The

Law Library of Congress Global Legal Research Center has reviewed this description for accuracy.

All currency conversions are based on a rate of 119 yen to one dollar, at www.xe.com

, as of October 19,

2015.

12

U.S. State Department “U.S. Relations with Japan Fact Sheet,” at

http://www.state.gov/r/pa/ei/bgn/4142.htm

.

10

(approximately $335,000).

13

There is also a national reconstruction surtax that is 2.1 percent of

the national income tax rate, and a local inhabitant tax that is 10 percent of taxable income.

Certain interest, including from bank deposits and government bonds, is separately taxed

and withheld at the source. The tax rate is 20.3 percent (15.3 percent for national income tax and

the reconstruction surtax, and five percent local tax).

Dividend income is generally aggregated with other sources of income and taxed at

progressive rates. Non-listed companies are required to withhold tax at 20.4 percent (20 percent

of which is national income tax plus the reconstruction surtax) from the gross amount of the

dividend payment, and the withheld tax amount is deducted from the tax imposed on the

aggregated income of an individual who receives a dividend subject to this withholding tax.

Dividends from listed companies are taxed at 20.3 percent (15.3 percent for national income tax

and the reconstruction surtax, and five percent local tax), which is also withheld at the source.

Individuals may elect to exclude dividends from listed companies from aggregate income.

Among capital gains of various assets, capital gains from the sale of certain securities

may be taxed similarly to dividend income. Capital gains from the sale of land and buildings are

taxed at various rates and are subject to different deduction amounts, depending on the use of the

property and whether the holding period qualifies as long-term (five years or more). Other

capital gains are added to aggregate income. In the case of long-term capital gain, 50 percent is

subject to tax.

Corporations

In general, corporations and all private business entities established in Japan are subject

to corporate income taxation on their worldwide income. Income earned by foreign subsidiaries

and dividends from foreign subsidiaries, however, is generally not included in a Japanese parent

company’s tax base.

The general national corporate tax rate is 23.9

14

percent.

15

Small and medium

corporations with contributed capital of no more than 100 million yen (approximately $838,000)

are taxed at 19 percent

16

on their annual net taxable income up to eight million yen

(approximately $67,000), and 23.9 percent on remaining taxable income. Corporations are

13

There are also general allowances available for resident individuals, and allowable deductions against

taxable income for items such as casualty losses, medical expenses, social insurance premiums, life insurance

premiums, earthquake insurance premiums, and charitable donations. The basic deduction for taxpayers is 380,000

yen (approximately $3,193).

14

For fiscal years beginning before April 1, 2015, the rate is 25.5 percent.

15

Taking into account all national and local taxes, the effective corporate statutory rate is generally 32.11

percent for the 2015 fiscal year, and 31.33 percent for the 2016 fiscal year.

16

This rate is reduced to 15 percent for tax years beginning before April 1, 2017.

11

subject to an additional size-based business tax. A special surtax, which is suspended through

March 31, 2017, is imposed on corporate capital gains from the sale of land located in Japan.

Dividends received from another domestic corporation are fully or partly excluded from

the corporate income tax base depending on the ratio in which the dividend-receiving

corporation owns the dividend-paying company’s shares. Interest received is fully taxed.

Dividends and interest are subject to a withholding tax at the rate described in the previous

section describing individual income tax, but the tax is generally creditable against corporate tax

liability and excess payments are refundable.

Japan provides corporate consolidation for 100-percent-owned domestic corporate

groups. Group taxation rules automatically apply to domestic companies with a 100 percent

relationship, but foreign parent companies or subsidiaries may not participate in consolidated tax

filing or group taxation. Dividends received from a 100-percent-owned domestic subsidiary are

exempt from corporate tax, and no gains or losses are recognized on asset transfers within a 100-

percent-owned group.

12

B. International Aspects of Domestic Japanese Tax Law

Residency

Japanese tax law provides different treatment for permanent residents, non-permanent

residents, and nonresidents. For tax purposes, a resident is any person who has a domicile in

Japan or has resided in Japan continuously for more than one year. A resident is non-permanent

for tax purposes if the resident is not a Japanese national but has lived in Japan for five years or

less, cumulatively, in the last 10 years. A nonresident is an expatriate residing in Japan for less

than one year.

A domestic company is a company whose head office or main office is in Japan.

17

Foreign companies are companies other than domestic companies.

Individuals

Permanent resident individuals are subject to tax on their income wherever paid or

derived. Non-permanent residents are subject to income tax on Japan-source income and on

income from other sources paid in Japan or remitted to Japan from abroad.

Nonresident individuals are typically subject to tax only on income from sources within

Japan. Passive income, such as dividends and interest, is subject to withholding tax. Dividends

are generally subject to withholding tax at a 20.4 percent rate, and the rate for certain listed

shares is 15.3 percent. Interest on bonds is generally subject to a 15.3 percent withholding tax.

Interest on loans used for operating a business in Japan is subject to a 20.4 percent withholding

tax. Royalties paid to nonresidents are subject to withholding tax at 20.4 percent. Sales proceeds

from Japanese real property are subject to withholding tax at a rate of 10.2 percent. Nonresident

individuals are generally not subject to Japanese income tax on capital gains, other than gains

from real property and securities.

Domestic companies

Domestic companies are subject to tax on their worldwide income. There is, however, a

95-percent exemption from corporate tax for dividends received by a domestic company from a

foreign subsidiary (the Foreign Dividend Exclusion Rule), with the exception that certain

Japanese shareholders must report currently any undistributed profits of “designated tax haven

subsidiaries.”

18

17

Therefore, all Japanese incorporate companies are resident because a company incorporated in Japan

under the Company Law, Civil Code, or other special laws must have its head office or main office in Japan. The

effective place of management or nationality of shareholders is not relevant for determining residence under Japan’s

tax law.

18

A designated tax haven subsidiary is a foreign company in which more than 50 percent of the shares are

owned directly or indirectly by Japan residents, and which is either not subject to any income taxation in its home

jurisdiction or is subject to an effective tax rate of 20 percent or less, as computed under Japan’s tax accounting

rules. A designated tax haven subsidiary may be fully or partially excluded from this regime if it satisfies (1) a

13

Foreign/nonresident companies

Foreign (non-domestic, or nonresident) companies are subject to Japanese income tax

only on their income from sources in Japan. Foreign companies not having a permanent

establishment in Japan are subject to withholding tax on gross payments as described in the prior

section about nonresident individuals.

Permanent establishment

If a nonresident individual or foreign company has a permanent establishment in Japan,

the business income that the nonresident derives is subject to income tax on a net basis at

progressive rates.

19

A foreign corporation or nonresident individual with a permanent

establishment in Japan is also subject to Japanese net basis income tax on all other Japan-source

income, such as investment income, under the “force of attraction” rule. Effective on April 1,

2016, however, the force of attraction rule will be replaced by the “attributable income method.”

Domestic-source income attributable to the business or activities of the permanent establishment

will be subject to net basis income tax, and other Japan source income not attributable to the

permanent establishment may be subject to gross basis withholding tax under the rules described

previously.

Controlled foreign corporation rules

Japanese tax law provides special rules pertaining to foreign corporations that are 50

percent owned, directly or indirectly, by domestic corporations and residents (controlled foreign

corporations, or “CFCs”). The “anti-tax-haven” rule provides that allocable shares of

undistributed income of a CFC is attributed, in the year in which it is derived (and irrespective of

whether it is distributed), to any domestic corporation owning directly or indirectly 10 percent or

more of the stock of a CFC if the tax burden of the foreign subsidiary is 20 percent or less.

20

Foreign tax credits and double tax relief

Japanese tax law allows relief from double taxation of domestic corporations and resident

individuals through a foreign tax credit. Foreign tax credits are subject to an overall limitation

generally equal to the product of Japanese income tax multiplied by the ratio of foreign source

income to taxable income. Surplus foreign tax credits and tax credit limitations may be carried

business test; (2) a substance test; (3) an administration and control test; and (4) either an independence test or a

local business test.

19

Japan’s tax law provides for three types of permanent establishment: a branch, factory, or fixed place of

business. In general, the application of this definition does not differ from the application of the term “permanent

establishment” in Japan’s tax treaties.

20

See previous discussion of “designated tax haven subsidiaries.” In general, income earned by a domestic

corporation’s foreign subsidiaries is not currently included in the tax base of the parent corporation until repatriated

via dividends or liquidation proceeds.

14

forward for three years. A taxpayer may elect to deduct foreign taxes for a taxable year in lieu of

claiming the foreign tax credit.

15

C. Other Taxes

In addition to the national income taxes described above, other taxes are levied at the

national or local levels. Additional national taxes include a broad based (VAT-type)

consumption tax; excise taxes on gasoline, other fuels, liquor, tobacco and certain other items;

inheritance and gift taxes; land value tax; registration and license taxes; and stamp tax.

Prefectural inhabitant tax, municipal inhabitant tax, and enterprise tax are taxes on

income collected at the local level, but subject to the general rules and rate limits prescribed by

the Local Tax Law (enacted by the national government). The bases for the individual and

corporate inhabitant taxes are almost the same as those of the corresponding national income

taxes. For individuals, the inhabitant tax rate on ordinary income is a flat rate of 10 percent, and

there are different rates for capital gains. The aggregate rates for the inhabitant taxes vary from

approximately 13 to 16 percent for corporations, depending on the size and location of the

business. The enterprise tax rates vary from approximately three to five percent for individuals

and three to seven percent for corporations, plus an added value levy and capital levy for

corporations.

From 2013 to 2037, a special reconstruction surtax of 2.1 percent applies to corporate and

individual income tax liability, including withholding tax on dividends, interest, royalties, and

employment income.

21

A foreign taxpayer eligible for the benefits of a Japanese income tax

treaty may be exempt from this tax.

21

This surtax is a special tax measure for the Tohoku earthquake reconstruction. It will continue until

2037.

16

IV. ECONOMIC OVERVIEW

A. Introduction

Tax treaties can be viewed as part of a set of economic arrangements, such as trade

agreements and bilateral investment treaties, reached between two countries to reduce the

economic cost of conducting cross-border economic activity. Trade agreements, for example,

may promote commerce between countries by lowering tariffs that countries impose on goods

and services imported from another country. Trade agreements may also support cross-border

commerce through non-tariff measures, such as the establishment of dispute resolution

mechanisms.

Like trade agreements, tax treaties reduce the cost of conducting cross-border economic

activity, but focus on limiting tax-related costs rather than tariff-related costs. By clarifying the

assignment of taxing authority between residence and source countries and eliminating the

double taxation of income, tax treaties reduce the uncertainty individuals and businesses may

face when deciding to work or invest in another country and can increase after-tax returns to

economic activity in cases where income may have been subject to double taxation or higher

rates of withholding tax. For example, consider a business resident in a country where all

income is taxed at a 15 percent rate, and assume the country has not concluded a tax treaty with

the United States. The business is contemplating an investment opportunity in the United States

where the economic returns come in the form of dividend payments, which are subject to a 30-

percent gross-basis withholding tax in the United States. In the absence of a tax treaty, the

dividends received by the business are taxed by the United States at 30 percent on a gross basis

and subject to no further home-country tax. However, if the United States pursues a treaty with

the country in which the business is resident, and the treaty eliminates withholding tax on

dividend payments, then the dividends the business receives as part of its investment are subject

to only home-country tax at 15 percent, thereby increasing the after-tax return on its investment

and making the investment opportunity more attractive. Furthermore, the business may find the

investment more attractive if there is a formal mechanism to address disputes over taxing

authority between its country of residence and the United States, which alleviates concerns over

double taxation and reduces uncertainty over the business’s overall tax payment on its

investment.

Tax treaties are often concluded between countries that already have significant

economic ties and have historically preceded, rather than followed, trade agreements, which

suggests that the conclusion of a tax treaty between two countries may provide some foundation

for future economic agreements.

22

The effect of tax treaties on economic activity between countries is ambiguous. On the

one hand, tax treaties can lead to a more efficient allocation of labor and capital between

countries to the extent that they eliminate or reduce tax-related barriers to economic activity.

The existence of a tax treaty between two countries can also have an indirect effect on

22

Peter Egger and George Wamser, “Multiple Faces of Preferential Market Access: Their Causes and

Consequences,” Economic Policy, vo. 28, no. 73, January 2013, pp. 143-187.

17

investment because the scope of a country’s tax treaty network can influence decisions to invest

in that country. However, a given tax treaty’s economic impact depends on the character and

volume of capital and labor flows between treaty countries and the scope for double taxation of

income in the absence of a tax treaty. If the scope for double taxation is limited, then tax treaties

may not be expected to have a significant impact on cross-border economic activity.

23

Moreover, for particular industries, tax treaties may cause investment to shift from one treaty

country to the other treaty country, just as lower barriers to trade may cause a shift in how

businesses make investment and employment decisions between countries. This shift in

investment may result in a more globally efficient allocation of investment but less investment in

a particular treaty country.

The empirical research on the economic effects of tax treaties has not yielded conclusive

results. On the one hand, a number of papers find that tax treaties have no or negative effect, and

the International Monetary Fund’s review of this literature suggests, at least for developing

countries considering tax treaties with developed countries, that whatever economic benefit may

arise from potential increases in foreign direct investment in the resulting from a tax treaty may

be offset by foregone tax revenue that results from limits on source-country taxation;

24

the

amount of capital that flows from a developed country to a developing country is, in general,

substantially greater than the amount of capital that flows from a developing country to a

developed country. On the other hand, some studies suggest that treaties have positive impacts

on cross-border investment.

25

One paper finds that, by facilitating the resolution of transfer

pricing disputes, the mutual agreement procedures in tax treaties can be particularly beneficial

for multinational firms that use inputs whose arm’s-length prices are difficult to determine.

26

Other papers find that while tax treaties encourage entry by firms in a particular country, they

have little impact on firms that already have a presence in the country.

27

In other words, tax

treaties may promote foreign direct investment, but largely through new investment by firms that

are first entering the market and not through increased investment by firms that are already

operating in the market.

23

The Treasury Department has indicated that establishing new tax treaties is partly determined by the

scope of double taxation with respect to income generated from U.S. direct investment. See Testimony of Robert B.

Stack, Treasury Deputy Assistant Secretary (International Tax Affairs), U.S. Department of the Treasury, Senate

Committee on Foreign Relations Hearing on the Proposed Tax Protocol with Spain and the Proposed Tax Treaty

with Poland, June 19, 2014, available at http://www.foreign.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/Stack_Testimony.pdf

.

24

International Monetary Fund, “Spillovers in Corporation Taxation,” International Monetary Fund Staff

Report, May 9, 2014.

25

Ibid.

26

Bruce A. Blonigen, Lindsay Oldenski, and Nicholas Sly, “The Differential Effects of Bilateral Tax

Treaties,” American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, vol. 6, no. 2, May 2014, pp. 1-18.

27

See Ronald Davies, Pehr-Johan Norback, and Ayca Tekin-Koru, “The Effect of Tax Treaties on

Multinational Firms: New Evidence from Microdata,” The World Economy, vol. 32, January 2009, pp. 77-110, and

Peter Egger, Simon Loretz, Michael Pfaffmayr, and Hannes Winner, “Bilateral Effective Tax Rates and Foreign

Direct Investment,” International Tax and Public Finance, vol. 17, December 2009, pp. 822-849.

18

B. Overview of Economic Activity Between the United States and Japan

Trade

With a gross domestic product (“GDP”) of $4.6 trillion in 2014, Japan is the third largest

economy in the world and one of the most significant trading partners of the United States.

28

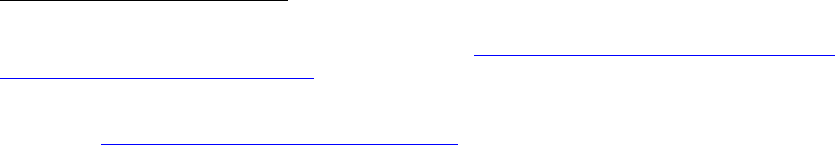

Japan is the fourth largest destination for U.S. exports in the world. Figure 1, below, charts the

volume of trade flows between the United States and Japan from 2003 to 2014 (in 2015 dollars).

$0

$50,000

$100,000

$150,000

$200,000

$250,000

$300,000

2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Figure1.−U.S.‐JapanTradeFlows,2003‐2014,

(in2015Dollars)

USExportsto Japan USImports fr omJapan

Source: Department of Commerce (Bureau of Economic Analysis) and calculations by the staff of the Joint

Committee on Taxation.

28

International Monetary Fund, World Economic Outlook Database (October 2015), available at

http://www.imf.org/external/pubs/ft/weo/2015/02/weodata/index.aspx

. The United States is the largest economy in

the world (GDP of $17.4 trillion in 2014) followed by China (GDP of $10.4 trillion in 2014). For additional

comparison, the collective GDP of the countries in the European Union was $18.5 trillion in 2014, and worldwide

GDP was $77.3 trillion.

19

In 2014, the United States exported $114.7 billion in goods and $46.7 billion in services

to Japan.

29

The largest categories of U.S. exports of goods to Japan were capital goods, except

automotive ($22.9 billion); industrial supplies and materials ($17.6 billion); and foods, feeds, and

beverages ($13.6 billion).

30

The largest categories of U.S. exports of services to Japan were

travel ($12.1 billion), transport ($9.5 billion) and charges for the use of intellectual property

($8.7 billion).

31

Japan is the fourth largest source in the world for U.S. imports. The United States

imported $136.7 billion in goods and $31.2 billion in services from Japan in 2014.

32

The largest

categories of U.S. imports of Japanese goods were capital goods, except automotive ($53.8

billion); automotive vehicles, parts, and engines ($49.9 billion); and consumer goods, except

food and automotive ($9.4 billion).

33

The largest categories of U.S. imports of services from

Japan were charges for the use of intellectual property ($12.4 billion), transport ($7.9 billion),

and government goods and services ($3.0 billion).

34

29

Bureau of Economic Analysis. These figures are calculated for purposes of the current account and

differ from figures reported in the monthly report on U.S. international trade in goods and services. Exports of

goods and services are calculated on the basis of receipts.

30

Ibid.

31

Ibid. Charges for the use of intellectual property include charges for the use of proprietary rights (such

as patents, trademarks, copyrights, industrial processes and designs including trade secrets, and franchises) as well

as charges for licenses to distribute or reproduce (or both) intellectual property embodied in produced originals or

prototypes (such as copyrights on books and manuscripts, computer software, and sound recordings” and related

rights (such as for live performances and television, cable, or satellite broadcasts. For additional discussion see

https://www.bea.gov/international/pdf/bach_concepts_methods/Royalties%20and%20License%20Fees.pdf

.

32

Ibid. These figures are calculated for purposes of the current account and differ from those reported in

the monthly report on U.S. international trade in goods and services. Imports of goods and services are calculated

on the basis of payments.

33

Ibid.

34

Ibid. Government goods and services include services supplied by and to enclaves, such as embassies,

military bases, and international organizations, as well as goods and services acquired from the host economy by

diplomats, consular staff, and military personnel located abroad (as well as by their dependents). For discussion of

other components of government goods and services, see http://www.bea.gov/international/pdf/concepts-

methods/ONE%20PDF%20-%20IEA%20Concepts%20Methods.pdf.

20

Foreign direct investment

Japanese direct investment in the United States

As of 2014, Japanese direct investment in the United States totaled $372.8 billion

(historical cost).

35

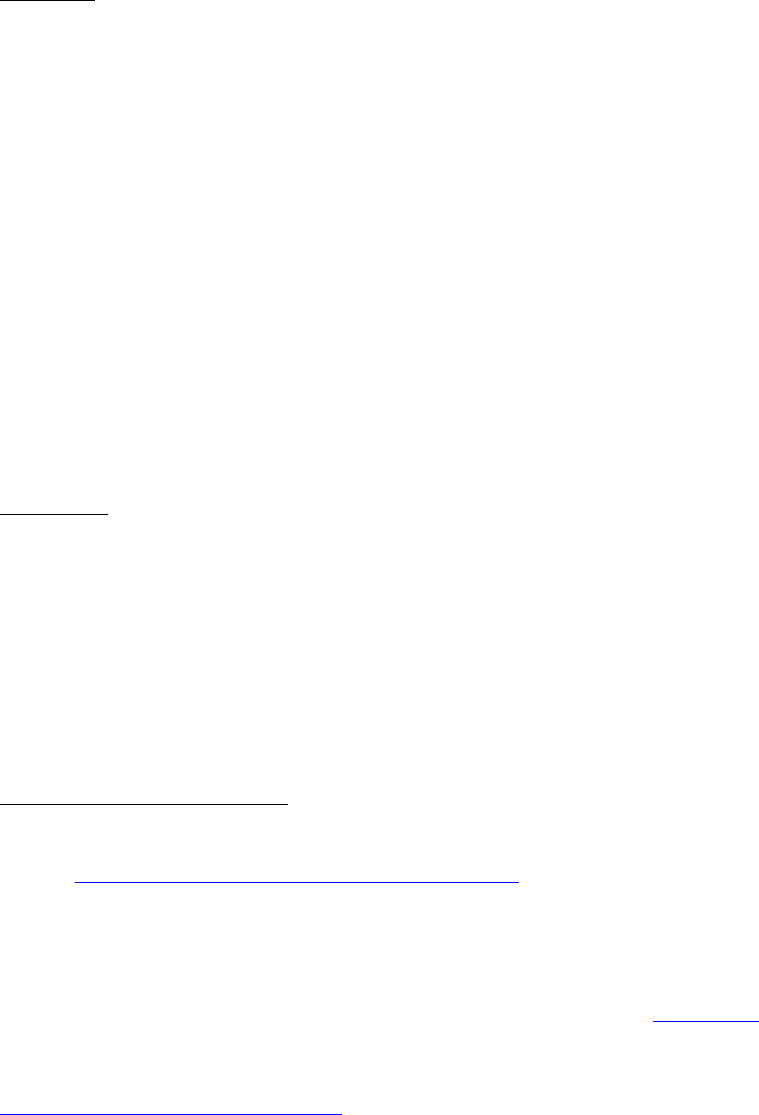

Figure 2, below, shows how the stock of Japanese direct investment in the

United States, as well as U.S. direct investment in Japan, has evolved from 1999 to 2014.

$0

$50,000

$100,000

$150,000

$200,000

$250,000

$300,000

$350,000

$400,000

1999 2000 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2006 2007 2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Figure2.−U.S.‐JapanDirectInvestmentPositions,1999‐2014

(Histori calCost)

JapaneseDirectInvestment inU.S. U.SDirectInvestmentin Japan

Source: Department of Commerce (Bureau of Economic Analysis).

35

The foreign direct investment figures reported in this section are calculated on a historical basis.

Foreign direct investment in the United States is defined as the ownership by a foreign investor of 10 percent or

more of a U.S. business; a similar definition applies to U.S. direct investment in Japan. In contrast, portfolio

investment generally reflects short-term activity in financial markets, or ownership by a foreign investor of less than

10 percent of a U.S. business. For data on foreign direct investment, see Nathan R. Hansen, and Ricardo Limés,

“Foreign Direct Investment in the United States for 2012-2014: Detailed Historical-Cost Positions and Related

Financial Transactions and Income Flows,” Survey of Current Business, September 2015. For definitions of foreign

direct investment and portfolio investment, see

https://www.bea.gov/international/pdf/bach_concepts_methods/Direct%20Investment%20Concepts.pdf

.

21

Table 1, below, compares the amount of Japanese direct investment in the United States

with direct investment sourced from other countries. Japan was the second largest source of

direct investment in the United States. Three other large sources of direct investment in the

United States, by country, were the United Kingdom ($448.5 billion), the Netherlands ($304.8

billion), and Canada ($261.2 billion).

36

By industry, the three largest targets for Japanese direct

investment in the United States were wholesale trade ($120.8 billion); manufacturing ($115.4

billion); and finance and insurance, except depository institutions ($44.9 billion). Income from

Japanese direct investment from all industries in the United States was $20.0 billion in 2014.

Table 1.−Top Ten Sources of Foreign Direct Investment

in United States in 2014 (Historical Cost) by Country

United Kingdom $448,548

Japan $372,800

Netherlands $304,848

Canada $261,247

Luxembourg $242,862

Germany $224,114

Switzerland $224,021

France $223,164

Belgium $89,097

Spain $58,138

Source: Department of Commerce (Bureau of Economic Analysis).

36

Ibid.

22

Employment arising from foreign direct investment made by majority-owned U.S.

affiliates of Japanese companies totaled 718,900 employees in 2012, making Japan the second

largest source of this type of employment in the United States; Japan trailed the United Kingdom

(962,900 employees) and was followed by Germany (620,200 employees). By industry, this

employment by Japanese companies was concentrated in manufacturing (326,300 employees),

wholesale trade (241,700 employees), and retail trade (241,700 employees). Total expenditures

on property, plant, and equipment by majority-owned U.S. affiliates of Japanese companies were

$42.7 billion in 2012, while research expenditures were $6.2 billion.

U.S. direct investment in Japan

As of 2014, U.S. direct investment in Japan totaled $108.1 billion (historical cost). Table

2, below, compares the amount of U.S. direct investment in the Japan with U.S. direct

investment in other countries. Japan was the 11th largest destination for U.S. direct investment

abroad. The three countries with the largest amount of U.S. direct investment (as measured by

historical cost) were the Netherlands ($753.2 billion), United Kingdom ($587.9 billion), and

Luxembourg ($465.2 billion). By industry, the three largest targets for U.S. direct investment in

Japan were finance and insurance, except depository institutions ($54.0 billion); manufacturing

($22.4 billion); and wholesale trade ($10.7 billion). Income for U.S. direct investment in Japan

from all industries totaled $10.7 billion in 2014.

Table 2.−Top Eleven Destinations for U.S. Direct Investment in 2014

(Historical Cost) by Country

Netherlands $753,224

United Kingdom $587,943

Luxembourg $465,160

Canada $386,121

Ireland $310,598

Bermuda $273,792

Australia $180,315

Singapore $179,764

Switzerland $152,879

Germany $115,533

Japan $108,315

Source: Department of Commerce (Bureau of Economic Analysis).

23

Business activities of U.S. multinational enterprises (“MNEs”)

U.S. MNEs conduct significant business activities through their Japanese affiliates

relative to their affiliates located in other countries. Table 3, below, provides statistics on the

activities of U.S. majority-owned foreign affiliates in Japan compared with U.S. majority-owned

affiliates based in other countries. Total sales by U.S.-majority-owned Japanese affiliates were

$235.9 billion in 2013, ranking them sixth among affiliates in other countries.

37

By comparison,

sales by U.K. affiliates were $753.4 billion, followed by Canadian affiliates ($694.8 billion) and

German affiliates ($382.9 billion).

38

Total employment by Japanese affiliates was 311,900

employees in 2013, ranking them eighth among affiliates based in other countries.

39

By

comparison, Chinese affiliates employed 1.7 million people in China, followed by Mexican

affiliates (1.4 million) and Canadian affiliates (1.2 million).

40

Table 3.−Activities of U.S. Majority-Owned Affiliates in Japan Compared to U.S.

Majority-Owned Affiliates in Other Countries in 2013

Japan Highest Second Highest Third Highest

Total Sales

(millions)

$235,883 Canada

($644,514)

United Kingdom

($643,098)

Singapore

($405,341)

Net Income

(millions)

$12,020 Netherlands

($141,896)

Luxembourg

($111,468)

Ireland

($105,245)

Capital

Expenditures

(millions)

$2,967 Canada

($33,841)

United Kingdom

($18,598)

Australia

($16,634)

R&D

Expenditures

(millions)

$2,070 Germany

($8,272)

United Kingdom

($5,346)

Switzerland

($3,735)

Employees 311,900 China

(1.4 million)

United Kingdom

(1.2 million)

Canada

(1.1 million)

Source: Department of Commerce (Bureau of Economic Analysis) and calculations by the staff of the Joint

Committee on Taxation.

37

Sarah P. Scott, “Activities of U.S. Multinational Enterprises in 2013,” Survey of Current Business,

August 2015.

38

Ibid.

39

Ibid.

40

Ibid.

24

Tax return data

Tax return data provide a complementary perspective on economic activity between the

United States and Japan. For tax year 2013, total U.S.-source income earned by Japanese

persons and potentially subject to withholding, as reported on Form 1042-S (“Foreign Person’s

U.S.-Source Income Subject to Withholding”), was $68.2 billion, with the principal types of

income being interest ($27.3 billion), dividends ($17.2 billion), and rents and royalties ($11.7

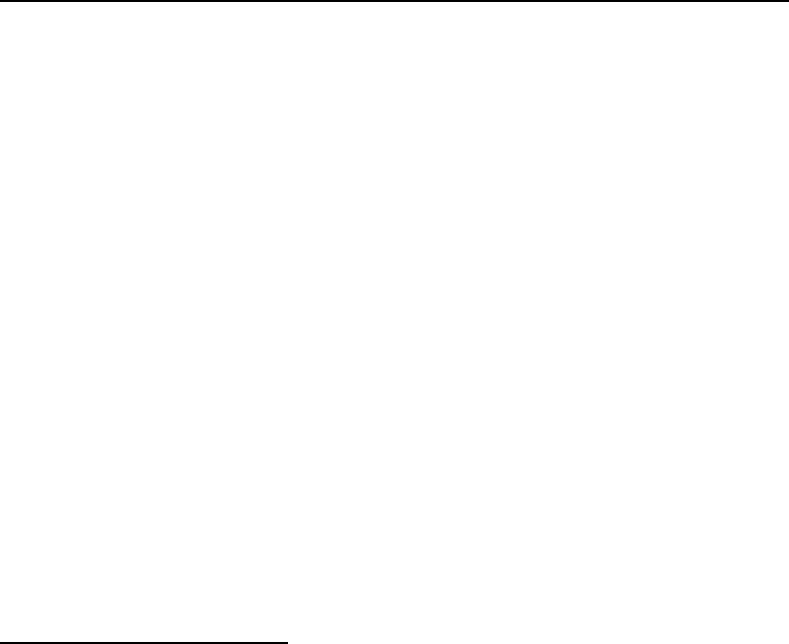

billion). Figure 3, below, decomposes the amount of U.S.-source income paid to Japanese

persons by payments subject to withholding and payments exempt from withholding. Only a

portion of U.S.-source income received by Japanese persons ($6.3 billion) was subject to U.S.

withholding tax; the amount of U.S. tax withheld was $395.1 million.

$0

$10,000,000

$20,000,000

$30,000,000

$40,000,000

$50,000,000

$60,000,000

$70,000,000

2005

2006

2007

2008

2009

2010

2011

2012

2013

Figure3.−U.S.‐SourceIncomeReceivedbyJapanesePersons,

2005‐2013

(Nomi nalDollars)

ExemptfromWithholding Subjec tto W ithholding

Source: Statistics of Income Division, Internal Revenue Service, and calculations by the staff of the Joint Committee

on Taxation.

For tax year 2010, Japanese-source gross income (less losses) reported on Form 1118,

which is filed by U.S. corporations claiming foreign tax credits, totaled $44.6 billion. Slightly

more than half of this income ($23.0 billion) was categorized as other income (which includes

income earned by Japanese branches of U.S. corporations). Income from rents, royalties, and

license fees was $7.8 billion, while income from dividends and interest were $7.7 billion and

25

$361.5 million, respectively.

41

Japanese taxes that were reported on these returns as paid,

accrued, or deemed paid totaled $6.4 billion million in 2010. Most of these taxes were eligible

for the deemed-paid tax credit ($5.3 billion). Taxes paid on rents, royalties, and license fees

were $15.9 million, while taxes paid on dividends and interest were $30.8 million and $8.0

million, respectively.

42

Data specific to controlled foreign corporations (“CFCs”)

Table 4, below, provides data from Form 5471 (“Information Return for U.S. Persons

With Respect to Certain Foreign Corporations”) and shows the number of U.S. CFCs in Japan

from 2004 to 2012 and certain operating statistics of those CFCs, including end-of-year assets;

current earnings and profits (less deficit) before income taxes; income taxes; dividends paid to

controlling U.S. corporations; and total subpart F income earned. In 2012, there were a total of

2,381 U.S. CFCs in Japan, which collectively held $748.4 billion in assets at the end of the year.

U.S. CFCs in Japan reported current pre-tax earnings and profits (less deficit) of $15.2 billion

and total subpart F income of $848 million. U.S. CFCs paid $3.7 billion in dividends to their

controlling U.S. corporations in 2012.

Table 4.−Selected Statistics of U.S. CFCs in Japan, 2004-2012

(Nominal Dollars)

Year

Number of

CFCs

End-of-

Year

Assets

(Millions)

Current

Earnings and

Profits

(Less Deficit)

Before Income

Taxes

(Millions)

Income

Taxes

(Millions)

Dividends

Paid to

Controlling

U.S.

Corporation

(Millions)

Total

Subpart F

Income

(Millions)

2004 2,265 $391,521 $15,105 $4,976 $1,288 $2,187

2006 2,554 $473,249 $15,746 $5,483 $1,616 $1,867

2008 2,730 $640,023 $6,311 $5,761 $2,191 $2,389

2010 2,570 $736,684 $19,849 $6,853 $4,034 $3,299

2012 2,381 $748,423 $15,169 $6,207 $3,661 $848

Source: Statistics of Income Division, Internal Revenue Service, and calculations by the staff of the Joint Committee

on Taxation.

41

The figure for gross income reported here includes income from the extraction of oil and gas as well as

foreign branch income. The data is obtained from Form 1118 filings. See Scott Luttrell, “Corporate Foreign Tax

Credit, 2010,” Statistics of Income Bulletin, Fall 2014.

42

Ibid.

26

V. EXPLANATION OF PROPOSED PROTOCOL

Article I

The proposed protocol amends paragraph 5 of Article 1 of the existing treaty by deleting

references to Article 20 of the existing treaty. Article 20, addressing income from teaching or

research, is deleted by Article VII of the proposed protocol (described below).

Article II

The proposed protocol replaces paragraph 4 of Article 4 of the existing treaty. The new

paragraph 4 provides that a person, other than an individual, who is resident of both the United

States and Japan (a “dual resident company”) will not be considered a resident of either the

United States or Japan for purposes of claiming any benefits provided by the proposed protocol.

The Technical Explanation clarifies that a dual resident company may claim the benefits

of the treaty that are not limited to residents. Additionally, a dual resident company may be

treated as a resident of one country for purposes other than claiming the benefits under the

proposed protocol. The Technical Explanation provides an example of a dual resident company

paying a dividend to a resident of Japan. The U.S. paying agent would withhold on the dividend

at the appropriate treaty rate (assuming the payee is otherwise entitled to treaty benefits) because

reduced withholding is a benefit enjoyed by the resident of Japan, not by the dual resident

company.

Information relating to a dual resident company can be exchanged under the proposed

protocol because Article 26 is not limited to residents.

This provision of the proposed protocol differs from the rule in the U.S. Model treaty.

Under the U.S. Model treaty, a dual resident company will be treated as a resident of the treaty

country under the laws of which it is created or organized if it is created or organized under the

laws of only one of the treaty countries. If this incorporation test does not resolve the question,

then the competent authorities will attempt to determine a single state of residence. Only if the

competent authorities do not reach an agreement on a single treaty country of residence will the

dual resident company not be considered a resident of either treaty countries for purposes of

claiming any benefits under the treaty.

Article III

Article III of the proposed protocol modifies the ownership and holding period

requirements of Article 10 of the existing treaty for elimination of source-country taxation of

dividends beneficially owned by a treaty country company.

The existing treaty provides that dividends paid by a company that is a resident of one of

the treaty countries and beneficially owned by a company that is a resident of the other treaty

country may not be taxed by the country of residence of the company paying the dividends if,

among other requirements, the beneficial owner of the dividends has owned, directly or

indirectly through one or more residents of either treaty country, more than 50 percent of the

27

voting stock of the company paying the dividends for the 12-month period ending on the date on

which entitlement to the dividends is determined.

The proposed protocol reduces the ownership threshold for elimination of source-country

tax to at least 50 percent of the voting stock of the company paying the dividends.

The proposed protocol reduces the required holding period to the six-month period

ending on the date on which entitlement to the dividends is determined.

By contrast with the existing treaty and proposed protocol, the U.S. Model treaty does not

provide a zero rate of source-country withholding tax on parent-subsidiary dividends. Zero-rate

provisions have, however, been included in thirteen in-force and proposed U.S. bilateral income

tax treaties and protocols.

43

The 50-percent ownership (existing treaty (more than 50 percent)

and proposed protocol (at least 50 percent)) and six-month holding period (proposed protocol)

requirements of the treaty with Japan are less strict than the zero-rate requirements of the other

12 treaties. Those other 12 treaties provide 80-percent ownership and 12-month holding period

requirements.

Article III of the proposed protocol also makes a conforming change to paragraph 9 of

Article 10 of the existing treaty by deleting a reference in that paragraph to paragraph 2 of

Article 13 of the existing treaty. Article V of the proposed protocol makes a substantive change

to paragraph 2 of Article 13 (described below) that makes the Article 10 reference to this

paragraph unnecessary.

Article IV

Article IV of the proposed protocol replaces Article 11 of the existing treaty, which

addresses the tax treatment of interest payments arising in one treaty country (the source country)

to residents of the other treaty country. While Article 11 of the existing treaty allows for source

country taxation of interest beneficially owned by a resident of the other treaty country, Article

IV of the proposed protocol brings the tax treatment of cross-border interest payments into closer

alignment with the rules described in the U.S. Model treaty and exempts such interest from

source-country taxation.

Article IV applies to interest arising in the source country that is beneficially owned by a

resident of the other treaty country. The proposed protocol does not define the term “beneficial

owner,” but the Technical Explanation indicates that the beneficial owner of the interest for

purposes of Article 11 is the person to which the income is attributable under the laws of the

source country. Special rules apply to interest earned through fiscally transparent entities for

purposes of determining the beneficial owner of the interest. In particular, residence country

principles control who is treated as deriving the interest, but source country rules are used to

determine whether that person, or another resident of the same country, is the beneficial owner.

43

The zero-rate U.S. income tax treaties are those with Australia, Mexico, and United Kingdom (zero-rate

provisions ratified in 2003); Japan and the Netherlands (2004); Sweden (2006); Belgium, Denmark, Finland, and

Germany (2007); France (2009); New Zealand (2010); and Spain (protocol with zero-rate provision not yet ratified).

28

An example in the Technical Explanation highlights how this special rule may work in practice.

In the example, FCo, a company that is a resident of Japan, owns a 50 percent interest in FP, a

partnership that is organized in Japan. Japan views FP as fiscally transparent under its internal

law and taxes FCo currently on its distributive share of the income of FP. Japan determines the

character and source of the income received through FP in the hands of FCo as if the income

were realized directly by FCo. As a result, if FP were to receive an interest payment arising in

the United States, FCo is treated as deriving 50 percent of the interest received by FP under

paragraph 6 of Article 4 of the existing treaty. In order to receive treaty benefits for this interest,

FCo must satisfy the beneficial ownership principles of the United States with respect to the

interest it derives.

The proposed protocol defines the term “interest” as interest from government securities,

bonds, debentures, and any other form of indebtedness, whether or not secured by mortgage and

whether or not carrying a right to participate in the debtor’s profits. The term includes premiums

attaching to such securities, bonds, or debentures. The term also includes all other income that is

treated as interest under the internal law of the country in which the income arises. Interest does

not include income treated as dividends under Article 10. Unlike the U.S. Model treaty, the

proposed protocol does not exclude from the definition of interest penalty charges for late

payment.

The reductions in source-country tax on interest under the proposed protocol do not apply

if the beneficial owner of the interest carries on business through a permanent establishment in

the source country and the interest paid is attributable to the permanent establishment. In such

an event, the interest is taxed under Article 7 of the existing treaty. This rule includes beneficial

owners that perform independent personal services through a permanent establishment because,

unlike the U.S. Model treaty but like the OECD Model treaty, independent personal services are

not addressed in a separate article.

The proposed protocol provides that interest is generally treated as arising in a treaty

country if the payer is a resident of that country.

44

However, if the interest expense is borne by a

permanent establishment, the interest will have as its source the country in which the permanent

establishment is located, regardless of the residence of the payer. Thus, for example, if a French

resident has a permanent establishment in Japan and that French resident incurs indebtedness to a

U.S. person, the interest on which is borne by the Japanese permanent establishment, the interest

would be treated as having its source in Japan. In the case of interest that is incurred by a U.S.

branch of a Japanese resident company, the Technical Explanation indicates that the interest

expense allocation rules under U.S. law determine the amount of interest expense that is treated

as having been borne by the U.S. branch for purposes of this article.

The proposed protocol addresses the issue of non-arm’s length interest charges between

related parties (or parties having an otherwise special relationship) by stating that this article

applies only to the amount of arm’s-length interest. Any amount of interest paid in excess of the

44

This is consistent with the source rules of U.S. law, which provide as a general rule that interest income

has as its source the country in which the payer is resident.

29

arm’s-length interest is taxable in the treaty country of source at a rate not to exceed five percent

of the gross amount of the excess. The treatment of excess interest under the proposed protocol

differs from the U.S. Model treaty, which provides that any amount of interest paid in excess of