1

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

August 2003

IP Strategies

www.vedderprice.com

Trends in patent, copyright, trademark and technology development and protection

TAX ASPECTS OF

SELLING AND LICENSING

INTELLECTUAL PROPERTY

The sale or license of a patent, copyright, trademark,

trade name, and other similar intellectual property right

(collectively, “Intellectual Property” or “IP”), whether

by agreement or as a result of litigation, has tax

consequences that transferors and transferees must be

aware of to ensure that IP is transferred on a tax

advantageous basis. The tax consequences of

transferring IP varies depending on whether the IP is

sold or licensed and varies depending on the particular

type of IP involved. Patents, know-how, copyrights,

trademarks and trade names each have unique U.S.

federal income tax consequences, as discussed in detail

below. Before these rules are discussed however, it is

important to first understand the federal income tax

consequences of selling and licensing Intellectual Property

in general.

SALES V. LICENSE — IN GENERAL

A person who sells/assigns all (or substantially all) of

their rights to Intellectual Property will generally be

treated as having “sold” their interest in the IP asset for

federal income tax purposes, and generally will be taxed

at capital gain rates. A buyer on the other hand, will

generally be required to depreciate or amortize the

purchase price of the acquired IP over a specific period

of time. This period of time depends on several factors

which are outside the scope of this article. However,

acquired IP is generally depreciated or amortized over a

mandatory 15 year period, the remaining useful life of

the IP or some other method permitted under the Internal

Revenue Code of 1986, as amended (the “Internal

Revenue Code”).

In contrast, when Intellectual Property is licensed,

the licensor typically has ordinary income to the extent

of money actually or constructively received from the

licensee, and the licensee typically has a business expense

deduction for the amount of royalties incurred.

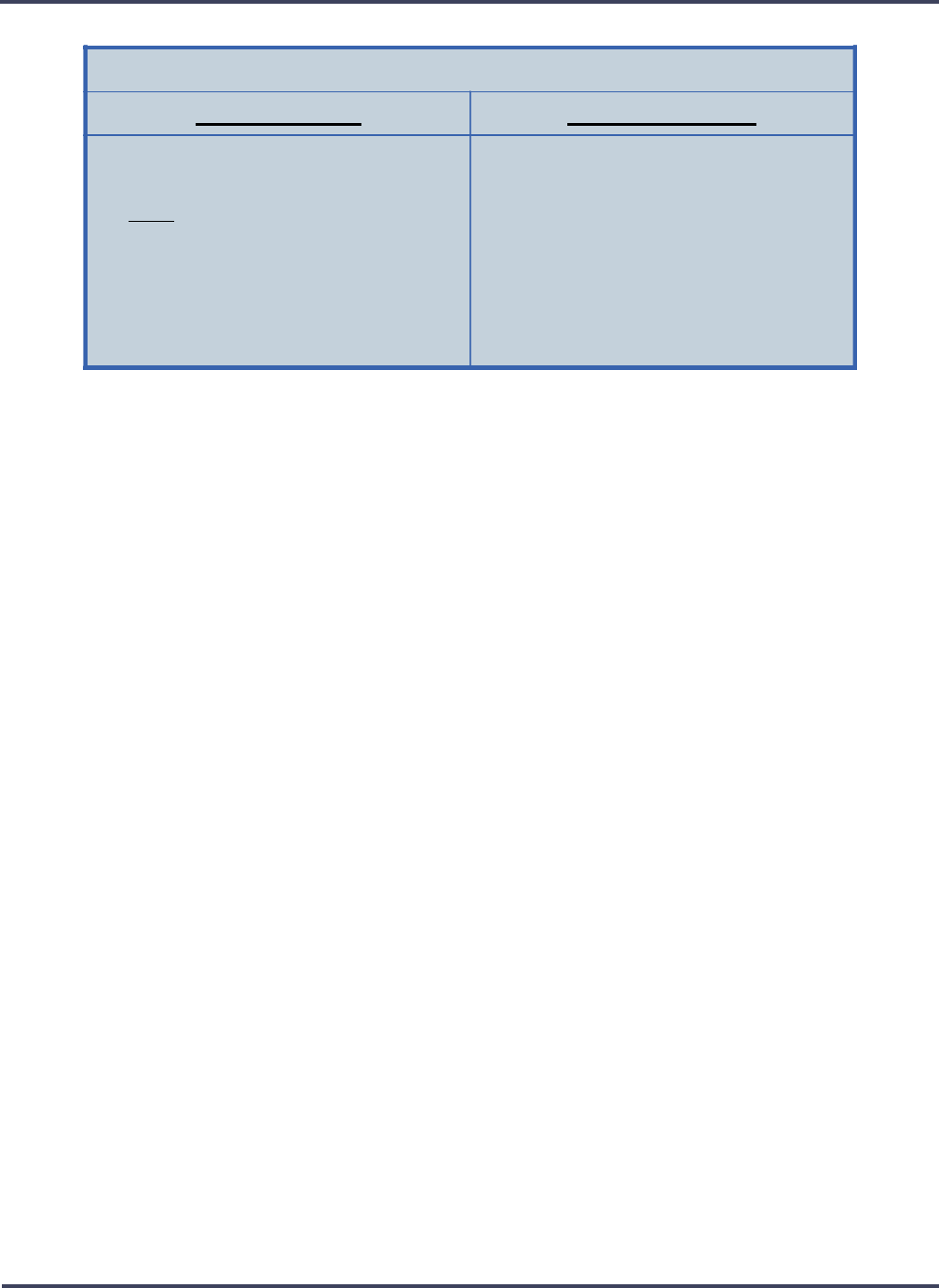

Example. The chart on page 2 illustrates these rules.

Assume a person transfers a patent worth $150 and the

transferor has an adjusted tax basis in the patent of $50.

Also assume that the patent had a remaining useful life

of 15 years, but, if licensed would only be licensed for

10 years.

As you will notice in the illustration on page 2, the

seller will net $135 ($150 purchase price – $15 tax) if the

IP is sold, but will only net $97.50 if the IP is licensed

(($15 annual royalty – $5.25 tax) x 10 years). However,

the licensor will still have an asset with a remaining useful

life of five years upon termination of the license.

These numbers reflect two key factors. First, when

you sell an asset, you can generally offset the purchase

price received with your basis, if any, in the asset sold,

whereas in a license transaction you cannot. And second,

as a result of federal tax legislation recently signed into

law, the marginal difference between the highest long-

term capital gain rate and the highest ordinary income

tax rate for individuals is 20%. The maximum long-term

capital gain tax rate is 15% and the maximum personal

income tax rate is 35% (note, corporations generally pay

the same rate of tax for net capital gains as ordinary

income (maximum 35%)). Furthermore, if a seller has

capital losses from unrelated transactions (for example

from current or previous stock market transactions), those

capital losses could offset some or all of the transferor’s

gain upon the sale of the IP, potentially netting zero federal

income tax on the transaction. Royalty income, unlike

sale proceeds, is ordinary income and cannot generally

be offset by any of the transferor’s unrelated capital

losses.

VEDDER PRICE

VEDDER, PRICE, KAUFMAN & KAMMHOLZ, P.C.

2

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

With respect to the buyer/assignee or licensee, the

tax consequences are different as well. The buyer in

this example will recover its cost over fifteen years

yielding a deduction of $10/year, while the licensee in

this example will have a business expense deduction of

$15/year for ten years. Note, the higher deduction is

only good if you have enough income to offset it.

Now that the general rules of taxation are laid out,

let’s turn to how you determine whether a transaction is

a sale or a license for federal income tax purposes.

DETERMINING WHETHER A TRANSACTION IS

A SALE OR A LICENSE

To determine whether a transaction is a sale or a license

for federal income tax purposes, several factors need to

be considered: (1) the type of IP (e.g., patent, copyright,

trademark, etc. — as discussed below); (2) the facts and

circumstances of the transaction; and (3) who has the

“benefits and burdens” of ownership.

The transfer of title, although indicative of a sale, is

not necessarily conclusive. Similarly, the name given to

the agreement (e.g., License Agreement) although

helpful, is also not conclusive. Some courts, have

analogized property rights to a “bundle of sticks.” The

more sticks transferred, the more likely the transaction

will be characterized as a sale for federal income tax

purposes. Conversely, the more sticks retained, the more

likely the transaction will be characterized as a license

for federal income tax purposes.

The Internal Revenue Service (“IRS”) can and will

recast a transaction to reflect its substance and not its

form. For example, the transfer of an exclusive license

for the life of an IP asset will likely be treated as a “sale”

for federal income tax purposes and not as a license.

This is because the transferor has relinquished all valuable

rights to the IP for remainder of its life. Stated differently,

the transferor has transferred all or substantially all of its

“bundle of sticks” causing it to be treated as a sale and

not a license. If a license is recharacterized as a sale by

the IRS, royalty payments would be recast as installment

sale payments. This could dramatically change the

anticipated tax consequences for both the transfer and

the transferee as demonstrated above.

SALES V. LICNSE — PATENTS, KNOW-HOW,

COPYRIGHTS, TRADEMARKS AND TRADENAMES

Each type of Intellectual Property is treated differently

for federal income tax purposes. This is a function of

specific legislative enactments and the way differing lines

of case law have developed.

Patents

A patent owner’s interest in its patent consists primarily

of the exclusive rights to “make, use, sell, offer to sell

and import” the patented item. Therefore, in order to

“sell” an interest in a patent, the sale must consist of the

transfer of all of these rights (or an undivided interest in

all these rights). If the patent owner does not part with

all of these exclusive rights (other than the retention of

certain de minimis rights), the transaction will generally

be treated as a license.

A patent owner might be able to “sell” less than all

of his or her rights to a patent and still obtain favorable

EXAMPLE

Sales Transaction License Transaction

Seller:

$100 ($150 - $50)

x 15% (Long Term Cap. Gain Rate)

$ 15 Federal Income Tax

Buyer:

$150/15 yrs. = $10/yr. deduction

Licensor:

$150/10 yrs. = $15/yr. Royalty

$15 x 35% = $5.25/yr. of Tax

Licensee:

Business expense deduction of $15/yr.

3

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

tax treatment. For example, the owner may be able to

sell the rights to a patent with in a particular restriction

(e.g., particular geographic area or product line).

However, the transferee must have the exclusive rights

to make, use, sell, offer to sell and import the patented

item within this restriction. Note, transferring less than

all of your rights to a patent must be done carefully to

ensure “sale” treatment.

Finally, unlike certain other IP, the method of paying

for a patent does not determined whether transaction is a

sale or license. Consideration can be fixed or contingent

(based on productivity or profits) and it can be payable

in one lump sum or over a period of time. However, if

you sell a patent and receive contingent consideration

payable over a period of time, care must be taken to

ensure “sale” treatment because this type of transaction

could resemble a license.

Special Rule for the Sale Of A Patent Created By

An Individual. The Internal Revenue Code carves out

a special exception for individual (i.e., not corporate)

inventors of a patent, and certain financial backers of

such inventors prior to the patent’s actual reduction to

practice. If such a person sells “all substantial rights” to

his or her patent (other then to a related party), the patent

will generally be considered a sale of a long-term capital

asset and taxed at favorable federal income tax rates

regardless of the length of time the patent or patent

application was held.

The phrase “all substantial rights” generally means

all rights to the patent which are of value at the time the

rights to the patent are transferred. This is a facts and

circumstances test. However, this test will not be satisfied

if the grant of rights is: limited geographically within

country of issuance; limited to a period of less than the

remaining life of the patent; less than all rights to fields

of use within the trade or industry; and, less than all of

the “claims or inventions” covered by the patent which

exist and have value at the time of the grant.

Long term capital gain treatment does not generally

apply to a transfer by an employee to his or her employer.

If the patent is acquired by an employer from its inventor/

employee, care must be taken to distinguish between

payments made for the transfer and salary payments.

The principal behind this is that the employee who was

“hired to invent” does not have any rights in those

inventions for which he or she can sell. Thus, payments

to the employee will typically be treated as additional

compensation and would be subject to ordinary income

and payroll taxes instead of capital gain taxes.

This special rule with respect to individual inventors

is specific only to patents. There is no counterpart rule

for copyrights, trademarks or know how. In fact,

copyrights have a rule that is practically the opposite to

this rule.

Know-How

Neither the Internal Revenue Code nor the regulations

thereunder define “know-how,” but the courts, including

the Tax Court, have characterized know-how as

“unpatented technology.” Know-how consists of things

such as technical data, secret processes and trade secrets.

To qualify as a “sale,” the transferor must generally

transfer all “substantial rights” to the know-how and

the transferee must generally have the right to bar

unauthorized disclosure of the know-how. If the

transferor retains any substantial rights to the know-how,

the transaction will likely be deemed a license and the

proceeds will be taxed as ordinary income.

The interesting difference with know-how is that,

even if a transfer qualifies as a sale for federal income

tax purposes, the know-how must be of a type to qualify

as a “capital asset” (as defined in the Internal Revenue

Code) to obtain favorable tax treatment. To qualify as

such an asset, an item being sold must be “property”

(another tax concept). The IRS has specifically stated

that two categories of know-how are property for capital

gain purposes: certain secret processes and formulas and

other secret information relating to a device or process

that is in the general nature of a patentable invention.

Case law has expanded on this definition, but each

situation is unique and must be carefully examined.

Therefore, although the transfer of know-how may

qualify as a “sale” for federal income tax purposes, the

transaction may nonetheless be taxed at ordinary income

tax rates.

Copyrights

The federal income tax treatment of a transfer of a

copyright depends on both the substance of the

transaction (e.g., how many “sticks” are transferred),

and who is selling the copyright. To get favorable tax

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

4

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

treatment, if available (see below), the seller must again

part with “all substantial rights” in a given medium of

expression. An exclusive license in a medium of

publication (e.g. movie rights) for the life of the

copyright is generally treated as a “sale” for federal

income tax purposes. A non-exclusive license will

generally be taxed and treated as a license.

Copyrights, like patents, have a special rule for the

person whose personal efforts created the copyrighted

work. However, this rule is the opposite as that for

patents. If the creator of a copyrighted work sells all of

his or her interest in the copyright, the sale will be taxed

at ordinary income tax rates and not capital gain tax

rates. The only people who can qualify to receive capital

gain tax treatment on the sale of a copyright is generally

anyone other than the person who created the

copyrighted work, certain persons for whom the

copyrighted work was created and their donees.

Because the creator of a copyrighted work is taxed

the same regardless of whether their interest is sold or

licensed, the creator may not care how the transfer is

structured. But there are other tax considerations a

creator-transferor should consider. For example, the

creator-transferor can offset the purchase price received

for the copyright with his or her basis in the copyright, if

any, in computing the amount of tax upon a sale, which

is not possible if the protected work is licensed. In

addition, a license transaction can generate passive

income which could have adverse tax consequences

(e.g., application of personal holding company rules).

Finally, the buyer may have a preference for tax purposes

as to whether the copyrighted work should be licensed

or purchased and the creator-transferor’s relative

neutrality could be utilized to structure a transaction

advantageous to both parties.

Trademarks and Trade Names

A trademark or trade name can generally be “sold” if

the transferor does not retain any “significant power,

right, or continuing interests” with respect to the subject

matter of the trademark or trade name. If, however, any

such rights (defined below) are retained, the transaction

will be generally be taxed and treated as a license for

federal income tax purposes.

The term “significant power, right, or continuing

interests” includes, but is not limited to, the following rights

with respect to the interest transferred: 1) a right to

disapprove any assignment of such interest, or any part

there of; 2) a right to terminate at will; 3) a right to

prescribe the standards of quality of products used or

sold, or of services furnished, and of the equipment and

facilities used to promote such products or services; 4) a

right to require that the transferee sell or advertise only

products or services of the transferor; 5) a right to require

that the transferee purchase essentially all of its supplies

and equipment from the transferor; and 6) a right to

payment contingent on the productivity, use, or

disposition of the subject matter of the interest

transferred, if such payments constitute a substantial

element under the transfer agreement.

These factors are objective indicia of a license and

are consistent with the “bundle of sticks” analogy. For

example, if a transferor has a right to terminate a

trademark at will, the trademark should be characterized

as a license because that would not be consistent with a

licensee’s ownership of the IP. Conversely, it would be

consistent with transferor’s ownership of the IP.

Finally, unlike patents and copyrights, contingent

payments may pose a problem. Contingent amounts

received or accrued by the transferor on account of a

transfer, sale or other disposition of a trademark or trade

name are generally treated as ordinary income. Amounts

are contingent if they depend upon the productivity, use,

or disposition of the transferred property. Therefore, if

a transaction is structured as a sale, the amounts received

may nonetheless be taxed as ordinary income if such

payments are contingent on the productivity, use or

disposition of the trademark or trade name.

CONCLUSION

Patents, know-how, copyrights, trademarks and trade

names each have unique federal income tax

consequences that transferors and transferees must be

aware of to ensure that IP is transferred on a tax-

advantageous basis.

5

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

MADRID PROTOCOL:

THE INTERNATIONAL

TRADEMARK APPLICATION

Effective November 2, 2003, the Madrid Protocol

Implementation Act of 2002 (MPIA) will introduce a

new and relatively easy and inexpensive way for U.S.

trademark application and registration holders (trademark

holders) to pursue multiple associated foreign trademark

registrations. Under MPIA, trademark holders will be

able to use a single international trademark application

to pursue multiple foreign trademarks from among the

fifty eight countries currently a party to the Protocol

Relating to the Madrid Agreement Concerning the

International Registration of Marks (Madrid Protocol).

A list of the countries, fees and other information can be

found on the World Intellectual Property Organization

(WIPO) web site: http://www.wipo.int/madrid/en/.

Advantages

The Madrid Protocol provides advantages in both the

application and post-registration phases of the foreign

trademark process. The advantages in the application

phase include:

1. the use of a single application regardless of

the number of countries designated;

2. the application need only be in English; and

3. the application is filed locally with the United

States Patent and Trademark Office (PTO).

The advantages in the post-registration phase include:

1. the existence of a guaranteed period (12 to 18

months) in which potential grounds of refusal

to protect a mark must be raised by the

individual designated states;

2. additional countries can be designated after

the initial registration;

3. a single location is provided for which to

record transfers, name and address changes,

etc.; and

4. a single request for renewal (10 year renewal

periods) paid to the International Bureau of

WIPO (IB) covers all of the designated states.

Application Phase

The application phase involves both the PTO and the IB.

Procedurally, a trademark holder files an international

application with the PTO. Next, the PTO certifies that

the information on the international application accurately

reflects the information relating to the corresponding U.S.

application or registration and then transmits the

international application to the IB. The IB then reviews

the international application to assure that the appropriate

fees have been paid and that the application otherwise

complies with the Madrid Protocol filing requirements.

As such, the IB does not perform any substantive

evaluation relating as to whether a mark qualifies for

protection in any forum or country. Once passing the

initial review, the IB registers the mark, publishes it in

the WIPO Gazette of International Marks, sends a

certificate to the owner, and notifies the designated

countries. If the international application is filed within

six months of the U.S. trademark application and claims

priority thereto, the international registration effective date

is the same as the U.S. trademark’s filing date and this

date is subsequently treated as the date that the mark

was filed with each of the designated countries.

Examination Phase

The examination phase involves both the designated

countries and the IB. Once notified by the IB, the

designated countries will examine the international

application under its own trademark laws. The trademark

office of any designated county has the right to refuse

trademark protection on any grounds on which an

application filed directly with such country could be

refused. Any such refusal is recorded in the IB’s

International Register. Further, the trademark holder has

the same right to contest the refusal of trademark

protection as an applicant who filed with the examining

trademark office directly. To the extent that the

examining trademark office limits an application to only

some of its originally designated goods, and where the

holder does not contest such limitation, the mark then

issues for such limited goods. An examining trademark

office must generally issue a refusal of registration within

twelve months from the date it was notified of the

designation, but may extend this period six additional

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

6

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

months by request. Beyond this extended eighteen month

period, a registration may be still refused based on an

opposition. However, within the eighteen month period

the examining trademark office must notify the IB of the

possibility of such an opposition. Therefore, at the end

of the eighteen month period the trademark holder will

know the status of his mark in all of the designated

countries.

Recordation

The Madrid Protocol provides for recordation of the

following items in the international register:

1. change of name or address of the holder;

2. change in ownership of the registration;

3. limitation of the list of goods;

4. renunciation of the protection with respect to

one or more of the designated countries; and

5. cancellation of the international registration.

Such recordation simply requires the filing of

a form with the IB and payment of an

associated fee.

The recordation is effective for all designated countries

concerned.

Five Year Probation Period

For five years after the international registration, such

registration is dependent on the corresponding

application or registration in the PTO. During this time

any withdrawal or cancellation of the PTO application,

whether occurring during this period, or occurring after

this period for an action begun during such period, results

in the cancellation of the international application. To

the extent that the withdrawal or cancellation is simply

a limitation of the original set of goods, the corresponding

international application will also be so partially

cancelled. Any such negative activity at the PTO can be

countered by transforming the international registration

into a series of national applications in the desired

designated countries without losing the date of the

original international registration. However, if the five

year term expires without cancellation of the international

application, the international application then stands on

its own independently from the originally filed PTO

application.

Current Status Of U.S. Regulations

The PTO is currently in the rulemaking process regarding

implementing the Madrid Protocol. The Federal Register

of March 28, 2003, includes a notice of proposed rule

making regarding the Madrid Protocol and includes a text

of the proposed regulations. The deadline for comments

was May 27, 2003 and a public hearing was held on

May 30, 2003.

DAMAGES AS A RESULT OF PATENT

INFRINGEMENT MAY NOW BEGIN

TO ACCRUE AS OF PUBLICATION

OF A PATENT APPLICATION

The Intellectual Property and Communications Omnibus

Reform Act of 1999 (the “Act”) requires that patent

applications filed on or after November 29, 2000 be

published 18 months after the application’s earliest

priority date unless the applicant does not intend to

foreign file. As a result of the Act, instead of waiting

until a patent issues, the patent laws now grant

provisional rights to a patentee to begin to recover

reasonable royalties as a result of patent infringement

beginning on the date of publication. Prior to the Act, a

patentee could collect damages, such as reasonable

royalties or lost profits, from an infringer only after the

patent issued. Now, if an applicant discovers that a

competitor is practicing the subject matter claimed in

the published application before the patent issues, the

applicant may begin to calculate reasonable royalties

starting with the publication of the patent application as

opposed to issuance of the patent. In addition, the

competitor can now analyze the published application

to determine the likely scope of the claims and mitigate

their damages by redesigning their product so as not to

infringe the claims in the published patent application.

Although the claims may later be broadened, the

information gleaned by reviewing the prosecution history

provides the competitor with a better understanding of

the risks of its own product development.

7

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

If an application is published, the Act grants limited

provisional rights to the applicant. According to the Act,

these limited provisional rights give the applicant the right

to a reasonable royalty against one who makes, uses,

offers for sale, sells, or imports in the United States the

invention as claimed in the published application, subject

to the following conditions. First, although the Act

provides for a reasonable royalty beginning on the date

of publication, no explicit provisions for lost profits or

any other type of damages as a result of patent

infringement are established in the patent statute.

Second, in order for reasonable royalties to begin to

accrue as of publication of the patent application, the

claims in the published application must be “substantially

identical” to the invention as claimed in the issued patent.

The meaning of “substantially identical” is not defined

in the statute. It may be that modification of a published

claim that substantively changes its scope will not be

considered to be substantially identical with an issued

claim. Therefore, in order to maximize the potential

provisional rights, applicants should attempt to have a

range of claims in the published application, e.g., the

range of claims should include claims having a broad

scope and claims having a narrow scope. This will

provide the applicant with a better chance of having some

of the published claims substantially identical to an

issued claim since a published narrow claim may issue

without modification even when a published broad claim

requires substantial modification. The Act also permits

applicants to redact portions of an application for

publishing. This enables an applicant to prevent

publication of material that will not be published

internationally.

The third condition that must be met in order for

provisional rights to be available is that the potential

infringer must be given “actual notice” of the published

application. What is required to provide “actual notice”

is not defined in the Act. However, the legislative history

suggests that the “actual notice” requirement is similar

to the actual notice requirement under 35 USC §287(a)

that the Federal Circuit has held requires that the patent

owner provide an affirmative communication of a

specific charge of infringement by a specific accused

article or process. Therefore, it is unlikely that merely

sending a copy of the published application, without more,

would satisfy the actual notice requirement of the Act.

Additionally, if the patentee is aware of a potential

infringer, the patentee may file a petition to make special

at the time of filing of the patent application to seek early

examination of the application and prompt issuance of a

patent, which potentially could occur before the eighteen

month period for publication.

The fourth condition is that the right to obtain a

reasonable royalty is only available if the infringement

action is brought within six years after the patent is issued.

This is consistent with 35 USC §286 that prevents the

recovery of damages for any infringement that was

committed more than six years prior to the filing of the

claim for infringement. Since the provisional rights mature

only when the patent issues, the ability to enforce these

rights for six years is analogous to the right to obtain

damages for a particular past act of infringement.

The Act’s provision requiring the publication of U.S.

patent applications is a significant departure from the

prior law by changing the point in time for calculating

the accrual of reasonable royalties. Although the effect

of the law is tempered by requiring the issued claims to

be substantially identical to the published claims, and

by requiring actual notice under the Act, the accrual of

damages beginning with publication provides significant

new options for patentees to expand their patent

enforcement and licensing programs.

VEDDER PRICE ADDS NEW

IP LAWYER

MARK A. DALLA VALLE

Mark A. Dalla Valle, formerly a partner with the law

firm of Wildman, Harrold, Allen & Dixon has joined the

growing Intellectual Property practice as a Shareholder

at Vedder Price.

Mr. Dalla Valle counsels clients in the field of

patents, trademarks and copyrights, concentrating in

serving technology clients, particularly those involved

in the design, manufacture and sale of electronic devices,

circuits and systems. He has written, filed and prosecuted

hundreds of patents in many areas of technology including

semiconductor fabrication and design, radio frequency

circuits and systems, fiber optic signal processing,

telecommunications circuits and systems, analog and

digital circuits and systems, and computer hardware and

software. He also provides validity and infringement

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

8

IP Strategies —August 2003

VEDDERPRICE

opinions as well as the preparation and prosecution of

trademark and copyright applications and technology

licensing agreements.

An electrical engineering graduate of DeVry Institute

of Technology (B.S.E.E.) and the University of Southern

California (M.S.E.E.), Mark received his legal education

at Loyola Law School (Los Angeles). Prior to entering

into private practice, he worked for approximately ten

years as a design engineer at Telease Technology and as

a test engineer, design engineer and engineering manager

at Hughes Aircraft Company.

Mr. Dalla Valle is licensed to practice in Illinois and

California. He is admitted before the U. S. District Courts

for the Northern, Central and Southern Districts of

California as well as the U. S. Court of Appeals for the

Ninth and Federal Circuits. Since 1990, he has been

registered to practice before the U. S. Patent and

Trademark Office.

IP Strategies is a periodic publication of Vedder, Price, Kaufman & Kammholz, P.C. and should not be construed as legal advice

or legal opinion on any specific facts or circumstances. The contents are intended for general informational purposes only, and

you are urged to consult your own lawyer concerning your own situation and any specific legal questions you may have.

We welcome your suggestions for future articles. Please call Angelo J. Bufalino, the Intellectual Property and Technology Practice

Chair at (312) 609-7850 with suggested topics, as well as other suggestions or comments concerning materials in this newsletter.

Executive Editor: Angelo J. Bufalino, Contributing Authors: David C. Blum, Themi Anagnos and Brent A. Boyd

© 2003 Vedder, Price, Kaufman & Kammholz, P.C.. Reproduction of this newsletter is permitted only with credit to Vedder, Price,

Kaufman & Kammholz, P.C.. For additional copies or an electronic copy of this newsletter, please contact Mary Pennington at her

e-mail address: [email protected], or (312) 609-5067.

Chicago

222 North LaSalle Street

Chicago, Illinois 60601

312/609-7500

Fax: 312/609-5005

About Vedder Price

Vedder Price is a national, full-service law firm with approximately 200 attorneys in Chicago, New York and Livingston, New Jersey.

Technology and Intellectual Property Group

Vedder, Price, Kaufman & Kammholz, P.C. offers its clients the benefits of a full-service patent, trademark and copyright law

practice that is active in both domestic and foreign markets. Vedder Price’s practice is directed not only at obtaining protection

of intellectual property rights for its clients, but also at successfully enforcing such rights and defending its clients in the court

and before federal agencies, such as the Patent and Trademark Office and the International Trade Commission when necessary.

We also have been principal counsel for both vendors and users of information technology products and services. Computer

software development agreements, computer software licensing agreements, outsourcing (mainly of data management via

specialized computer software tools, as well as help desk-type operations and networking operations), multimedia content

acquisition agreements, security interests in intellectual property, distribution agreements and consulting agreements, creative

business ventures and strategic alliances are all matters we handle regularly for our firm's client base.

V

EDDER

,

P

R ICE

,

K

AUFMA N

&

K

AMM HOLZ

, P.C.

New York

805 Third Avenue

New York, New York 10022

212/407-7700

Fax: 212/407-7799

New Jersey

354 Eisenhower Parkway, Plaza II

Livingston, New Jersey 07039

973/597-1100

Fax: 973/597-9607

www.vedderprice.com