2022 Virginia Data Center Report

THE IMPACT OF DATA CENTERS

ON THE STATE AND LOCAL

ECONOMIES OF VIRGINIA

March 2022

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

SPONSORS

We would like to acknowledge and thank the following sponsors of this report:

Lead Sponsors

Supporting Sponsors

Report Prepared by:

© 2022 Northern Virginia Technology Council

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

About Mangum Economics, LLC

• Policy Analysis

Identify the intended and, more importantly, unintended consequences of proposed legislation and

other policy initiatives.

• Economic Impact Assessments and Return on Investment Analyses

Measure the economic contribution that businesses and other enterprises make to their localities.

• Workforce Analysis

Project the demand for, and supply of, qualied workers.

The Project Team

David Zorn, Ph.D.

Director, Technology and Special Projects Research

A. Fletcher Mangum, Ph.D.

Founder and CEO

Martina Arel, M.B.A.

Director, Economic Development and Renewable Energy Research

• Cluster Analysis

Use occupation and industry clusters to illuminate regional workforce and industry strengths and

identify connections between the two.

Mangum Economics, LLC is a Glen Allen, Virginia based rm that specializes

in producing objective economic, quantitative, and qualitative analysis in

support of strategic decision making. Much of our recent work relates to

IT and Telecom Infrastructure (data centers, terrestrial and subsea ber),

Renewable Energy, and Economic Development.

Examples of typical studies include:

1

Acknowledgments

This report was made possible in part by the unique data supplied by the Loudoun County Department

of Economic Development (especially, Alex Gonski and Buddy Rizer) and the Prince William County

Department of Economic Development (especially Allisha Abraham, Thomas Flynn, and Jim Gahres). Fairfax

County Economic Development Authority (especially Catherine Riley and Stephen Tarditi) also provided

important information for the report.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

About the Northern Virginia Technology Council

The Northern Virginia Technology Council (NVTC) is the trade association representing the

National Capital Region’s technology community. As one of the nation’s largest technology

councils, NVTC serves companies from all sectors of the industry, from small business and

startups to Fortune 100 technology companies, as well as service providers, academic

institutions, and nonprot organizations. Nearly 500 entities make up the NVTC membership

and look to the organization as a resource for networking and educational opportunities,

peer-to-peer communities, policy advocacy, industry promotion, fostering of strategic

relationships, and branding of the region as a major technology center.

If you are interested in joining NVTC, please contact Steve Upton, NVTC Chief Growth

Ocer at supton@nvtc.org.

website: nvtc.org

email: nvtc@nvtc.org

phone: 703-904-7878

2

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Executive Summary

Data Centers Drive Investment in Virginia

Economic Prole of Data Centers in Virginia

The Northern Virginia Data Center Market in 2021

Rapidly Raising Wages in Virginia Data Centers

The Regional Distribution of Data Center Investment in Virginia

The Impact of Data Centers on Virginia State and Local Economies

Virginia Statewide

Central and Coastal Virginia

Investment Highlight - Community Action Grants

Northern Virginia

Investment Highlight - The Northern Virginia Community College Programs

Investment Highlight - New Data Center Expansions in Fairfax County

Southern Virginia

Investment Highlight - SOVA Innovation Hub

Valley and Western Virginia

Investment Highlight - Project Oasis and Mineral Gap

Data Centers’ Contribution to State and Local Government Budgets

Statewide and Regional Tax Collections Associated with Data Centers

Data Centers Contribute to Local Government Budgets

Data Centers’ High Local Benet to Cost Ratio

Local Data Centers Reduce the Burden on the State Education Budget

Virginia’s Data Center Sales and Use Tax Exemption

Virginia Treats Data Centers Like Other Capital-Intensive Industries

JLARC’s Evaluation of the Data Center Incentive

The Incentive Helps to Attract Some Data Centers that Do Not Qualify for the Incentive

National Context for Virginia Incentives

Competition Between States

New York - New Jersey - Connecticut

Illinois - Indiana

6

8

9

10

12

14

15

15

16

17

18

20

19

21

22

22

23

23

27

26

27

28

30

30

32

32

4

8

17

3

32

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Executive Summary

Data centers are the major drivers of investment in Virginia. According to information from the Virginia

Economic Development Partnership (VEDP), in 2021, 62% ($6.8 billion) of all the new investment announced

by VEDP was from new and expanding data centers.

The investment in data centers in Virginia is also driving investment in businesses in the data center supply

chain. Some specic examples of new investment in Virginia associated with data centers include:

• Aggreko establishing its North American data center headquarters in Loudoun County

• Anord Mardix adding a second manufacturing plant in Henrico County

• Hanley Energy establishing its U.S. headquarters and manufacturing plant in Ashburn

• Munters Group investing $36 million in a new manufacturing facility in Botetourt County.

1

The concentration of data centers in Virginia spurred the construction of the subsea cable landing in Virginia

Beach that serves the MAREA, BRUSA and Dunant cables. Conuence Networks also plans the construction

of Conuence-1, a festoon cable connecting Virginia Beach to New Jersey, South Carolina and Florida.

Virginia now has data centers located throughout the state, from Wise County and Harrisonburg in the Valley

and Western Virginia, to Mecklenburg County in Southern Virginia, to Henrico County and Virginia Beach in

Central and Coastal Virginia, to Loudoun County in Northern Virginia, and other localities.

Northern Virginia has the largest data center market in the United States. As of 2021, the data center

inventory in Northern Virginia exceeds that of the next 5 largest markets combined. The compound annual

rate of growth in data centers in Northern Virginia from 2014 to 2021 was 25%. In comparison,

Dallas-Fort Worth, the next fastest growing area, had compound annual growth rate of 10%. From 2018 to

2021, the total data center capacity in Northern Virginia more than doubled.

Between 2001 and 2020, the average private sector employee of a Virginia data center saw their gross

income go up 70% faster than the average private sector employee in Virginia. We estimate that in 2021,

data center employed 5,550 Virginians, not counting construction workers building data centers in the state.

Approximately 88% (4,920) were working in Northern Virginia, while six percent (330) worked in Southern

Virginia, ve percent (250) worked in Central and Coastal Virginia, and one percent (50) worked in the Valley

and Western Virginia. The accumulated capital investment in data centers across the state amounts to

$126 billion in 2021 dollars. Virginia data centers spent $5.4 billion in 2021 for operational expenses, the

majority of which goes for stang and power.

1

https://roanoke.org/2021/03/25/munters-group-ab-to-invest-36-million-in-botetourt-county/

4

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

In 2021, the data centers in Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 5,550 operational jobs and 10,230 construction and manufacturing jobs

• $1.6 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $7.5 billion in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, the total impact on Virginia

from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 45,460 supported jobs

• $3.6 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $15.3 billion in economic output

For every job inside a Virginia data center, there are 4.1 additional jobs that are supported in the rest of the

Virginia economy.

We estimate that in 2021, data centers were directly and indirectly responsible for generating $174 million in

state revenue and $1 billion local tax revenue in Virginia.

In 2020, the local benet to cost ratios associated with the industry were:

• Loudoun County - for every $1.00 in county expenditures that data centers were responsible for

generating, it provided approximately $13.20 in tax revenue

• Prince William County - for every $1.00 in county expenditures that data centers were responsible for

generating, it provided approximately $13.50 in tax revenue

Because of the way that the state of Virginia subsidizes local education budgets, without data centers in

Loudoun and Prince William counties, the State of Virginia would have to reallocate $90.5 million in State

education funding away from other Virginia localities to provide $73 million in additional funding to

Loudoun County, and $17.5 million in additional funding to Prince William County.

In 2019, The Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission (JLARC) published an evaluation of Virginia’s

data center and manufacturing incentive programs. JLARC found:

• 90% of the data center investment made by the companies that received the sales and use tax

exemption would not have occurred in the state of Virginia without the incentive

• In 2017, the State took in $1.09 in state tax revenue from data center related activity for every $1 of

potential state tax revenue that was exempted from qualifying data centers

• In 2016, the data center incentive was revenue neutral - it generated $1 in additional state tax revenue

for every $1 of potential state tax revenue that it exempted

• From 2013 through 2017, on average, the State recovered 75 cents in state tax revenue for every one

dollar of potential tax revenue exempted from qualifying data centers

Over 30 states have some type of incentive to attract data centers to their states. In the last couple of years,

Arizona, Connecticut, Idaho, Maryland, North Dakota, Pennsylvania, and Utah have all enacted or expanded

sales and use tax incentives targeting data centers for economic development.

5

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Data Centers Drive Investment in Virginia

Data centers are the major drivers of investment in Virginia. Investment in the state comes in the form of the

construction and operation of the data centers themselves, plus investments in Virginia made by businesses

that supply and support data centers in the state.

According to information from the Virginia Economic Development Partnership (VEDP),

2

in 2021, 62%

($6.8 billion) of all of the new investment announced by VEDP was from new and expanding data centers.

In 2020, data centers accounted for 81% ($7.9 billion) of all of the new investment that VEDP announced. As

explained below, we estimate that the accumulated capital investment of data centers in Virginia amounts

to $126 billion in 2021 dollars employing 5,550 operational workers.

The investment in data centers in Virginia is also driving investment in businesses in the data center

supply chain. Some specic examples of new investment in Virginia associated with data centers include

the $36 million investment by Munters Group in a new manufacturing facility in Botetourt County for

200 employees.

3

Munters is a global manufacturer of air treatment and climate control equipment,

including data center cooling systems. A signicant portion of the cost of building a data center goes to the

equipment needed for cooling. Michael Gantert, the president of Data Centers at Munters, stated that,

“A move to the Roanoke region will allow for the expansion that is needed for the Data Centers

business in the U.S.”

4

Another example of recent data center supply chain investment in Virginia is Hanley Energy establishing its

U.S. headquarters and manufacturing plant in Ashburn.

5

The Irish company provides energy-monitoring

products and services for data centers. The new plant and headquarters will employ 170 new workers by the

end of 2022. Additionally, Aggreko established its North American data center headquarters in

Loudoun County. The British company produces temporary power generation and energy story equipment

for data centers. Mike Clemson, the head of Aggreko’s North American Data Center Division, stated, “The

choice to establish a presence in Loudoun was a natural one, as virtually all of our data center customers

are present in the Data Center Alley. The opportunity for us to grow our data center business in

Loudoun County is tremendous.”

6

In Henrico County in 2019, Anord Mardix, a global power distribution and management manufacturer,

spent almost a million dollars and added 51 new jobs for a second manufacturing plant. The power

switchgear produced in the company’s two manufacturing facilities is used in data centers and other critical

infrastructure businesses. Chairman of the Henrico County Board of Supervisors, Tyrone Nelson, said,

"Anord Mardix's success supports Henrico's growing data center cluster as they supply critical power

infrastructure to data centers and mission-critical facilities across the globe."

7

2

https://announcements.vedp.org/Announcements/

3

https://roanoke.org/2021/03/25/munters-group-ab-to-invest-36-million-in-botetourt-county/

4

https://www.munters.com/en-us/media/news/global-news/2021/munters-relocates-in-the-us-to-expand-data-center-business/

5

Dan Swinhoe, “Hanley Energy expands in Virginia, will base US headquarters in Loudoun County,” May 25, 2021.

6

LoudounNow, "Aggreko to Establish Data Center Division Headquarters in Loudoun,” July 10, 2021.

7

https://www.governor.virginia.gov/newsroom/all-releases/2019/january/headline-837867-en.html

6

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

The concentration of data centers in Virginia spurred the construction of the subsea cable landing in Virginia

Beach that serves the MAREA cable going to Spain, the BRUSA cable going to Puerto Rico and Brazil, and

Google’s Dunant cable going to France. Conuence Networks also plans the construction of Conuence-1,

a festoon cable connecting Virginia Beach to New Jersey, South Carolina, and Florida. These subsea

cables enable very high-speed connections which businesses will increasingly need for the deployment

of “Industry 4.0” technologies. The Globalinx and Telxius data centers in Virginia Beach oer collocated

connections to the MAREA and BRUSA cables. The DP Facilities data center in Wise County takes advantage

of the MidAtlantic Broadband Communities Corporation ber connections to the MAREA subsea cable.

The data centers in Northern Virginia and the cable landing station in Virginia Beach attracted Facebook to

invest in its large data center in Henrico County, midway between the two locations. Additionally, QTS has

connected its large data center and network access point in Henrico County to the subsea cables in Virginia

Beach, oering very low latency connections to Europe and Brazil.

The technology companies that own and operate data centers have made commitments to use renewable

energy for their operations. In general, they prefer to have the renewable energy that they purchase

generated close to their facilities. That has created a strong demand for investments in renewable energy in

Virginia. Dominion Energy is spending over nine billion dollars to build a wind farm o Virginia Beach which

will create thousands of jobs in Hampton Roads. And the Solar Energy Industries Association reports that

3,444 megawatts (MW) of solar generation capacity has been installed in Virginia.

8

Using general industry

averages of one million dollars of investment per MW, the data centers in Virginia have helped to create

demand for $3.4 billion of investment in solar energy projects in the state.

Virginia’s data center tax incentive programs are investments in not only in data centers, but also in the

manufacturing, energy, and service businesses that are associated with them. The incentive sends a clear

signal to potential investors worldwide that the business climate in Virginia is friendly to the high-tech

industry.

This report quanties the signicant contribution that data centers make to the state of Virginia and its

localities, and it puts Virginia’s data center incentive program into the national context of the competition to

attract data centers.

8

https://www.seia.org/state-solar-policy/virginia-solar

7

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Economic Prole of Data Centers in Virginia

Virginia now has data centers located throughout the state, from Wise County and Harrisonburg in the Valley

and Western Virginia, to Mecklenburg County in Southern Virginia, to Henrico County and Virginia Beach in

Central and Coastal Virginia, to Loudoun County in Northern Virginia, and other localities. This report shows

how data centers in every part of the state make an important economic contribution to employment and

taxes in every region and to the state as a whole. We begin with an update on the remarkable data center

market in Northern Virginia.

The Northern Virginia Data Center Market in 2021

Northern Virginia has the largest data center market in the United States. As of 2021, by our calculations

based on data from CBRE

9

and JLL

10

, the data center inventory in Northern Virginia exceeds that of the

next 5 largest markets (Chicago, Dallas-Fort Worth, Silicon Valley, New York/Tri-State Area, and Phoenix)

combined.

Northern Virginia’s place at the top of the data center market is a relatively recent development. In 2016,

Northern Virginia had just supplanted the New York market as the largest data center market in the United

States. In 2017, the New York/Tri-State area had fallen to become the sixth largest data center market. A 2011

report on the data center market in the United States contains only one mention of Virginia in four pages,

“Reston, VA has excess supply and new construction will be minimal for a few years.”

11

The locations that

were highlighted as important in the industry were Chicago, Silicon Valley, Southern California, Phoenix,

New York, St. Louis, Washington State, Boston, Minneapolis, Denver, and Charlotte. Regarding what has

become the second largest data center market, the report says, “Dallas has excess capacity and growth

remains slow.”

This illustrates the uid nature of the data center market and the speed with which market conditions can

change in the industry. Once-hot markets can cool o rapidly. In 2017, the data center market in Phoenix

had enormous growth, but between the second half of 2018 and the rst half of 2019, Phoenix saw net

outows of 26.5 MW worth of tenants, which is almost the same amount that Northern Virginia added in the

same period.

12

The computer equipment in data centers is replaced on average every three to ve years.

Should circumstances warrant it, data center tenants can move from one location to another and leave

signicant vacancies in colocation data centers.

9

CBRE, Digital Infrastructure in 2021: The Search for Land, Space, Power and Connectivity, North America Data Center Trends

Report, H1 2021.

10

JLL, H1 2021 Data Center Outlook.

11

ESD (Environmental Systems Design, Inc.), 2011 Data Center Technical Market Report. February 2011.

12

CBRE, Large Supply Pipeline Sets Stage for Market Growth in 2019 North American Data Center Report H1 2019.

8

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

As large as the data center market in Northern Virginia is, the growth of data centers in Northern Virginia is

even more impressive. We estimate that the compound annual rate of growth in data centers in Northern

Virginia from 2014 to 2021 was 25%.

14

In comparison, Dallas-Fort Worth, a fast growing area, had a

compound annual growth rate of 10%.

15

From 2018 to 2021, the total data center capacity in Northern

Virginia more than doubled.

Rapidly Rising Wages in Virginia Data Centers

One of the key characteristics of data centers is that they are extremely capital intensive. In other words, data

centers employ a relatively small number of highly skilled and highly paid people to operate and maintain a

large amount of expensive equipment. Therefore, it is useful to also look at trends in private sector average

annual wages in the industry.

Between 2001 and 2020 the average annual private sector wage in the data processing and hosting industry

in Virginia grew from $61,117 to $134,308 – a 120% increase.

16

13

Mangum Economics estimates based on 2021 data from CBRE and JLL.

14

Mangum Economics estimates based on data from CBRE and JLL.

15

Mangum Economics estimates based on data from CBRE and JLL.

16

Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

9

Figure 1 shows the 18 largest data center markets in the United States, as identied by CBRE and JLL. The area of

each circle indicates the relative amount of power capacity in each market.

Figure 1: Relative Sizes of Largest Data Center Markets (megawatts of power capacity) - 2021

13

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 10

17

Data Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

18

https://demographics.coopercenter.org/virginia-regions

19

https://www.investswva.org/project-oasis

In comparison, over the same period average private wages across all industries in Virginia went from

$36,525 to $62,250 – an increase of 70%.

17

In other words, over the 19-year period, the average private

sector employee of a Virginia data center saw their gross income go up 70% faster than the average private

sector employee in Virginia.

This combination of growing investment and rapidly rising wages make data centers one of Virginia’s highest

performing industries and an important (and growing) contributor to a strong and robust state economy.

Moreover, in a state such as Virginia where roughly two-thirds of state revenue comes from personal income

tax, high growth/high wage industries such as data centers also play a disproportionate role in ensuring the

health of the State’s budget.

The Regional Distribution of Data Center Investment in Virginia

As impressive as the data center market in Northern Virginia is, in this section, we describe how data center

investment is distributed across the state. In this report the method that we use to identify data center

investment is dierent than we have used for previous editions of this report for NVTC. This time we use

detailed information on the specic identity, exact location, and size of data centers in Virginia. Using a

proprietary data center cost model that we built and validated based on information from various industry

sources, we translate data center size information into estimates of employment, local capital investment,

and operating costs. We have used this model in projects across the United States.

For the purpose of this report, we have divided the state of Virginia into four regions: Northern Virginia,

Central and Coastal Virginia, The Valley and Western Virginia, and Southern Virginia. Figure 2 shows the way

we have dened these regions by locality. To identify these four regions, we started with the eight regions

identied by the Weldon Cooper Center Demographics Research Group that are based on “communities’

shared demographic, social, economic, and geographic characteristics.”

18

We then grouped the eight

demographic regions into four regions of data center investment that have dierent catalysts for data center

development. Data center development in Northern Virginia is motivated by the existing bulk of data center

development in the area, as well as proximity to the federal government and tech companies in the area.

Development in Central and Coastal Virginia is signicantly due to proximity to the subsea cable landing

station in Virginia Beach and to the major terrestrial ber route running from Northern Virginia south to

Raleigh, North Carolina. Data center development in Southern Virginia has the security advantages provided

by distance from major population centers while still being centrally located on the East Coast of the United

States. For the Valley and Western Virginia, data center development can continue to occur fostered by a

robust ber network and access to geothermally-cooled water.

19

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 11

Figure 2: Four Sub-State Regions

We estimate that in 2021, 5,550 Virginians were employed in data centers, not counting construction

workers building data centers in the state. Approximately 88% (4,920) worked in Northern Virginia, while

six percent (330) worked in Southern Virginia, ve percent (250) worked in Central and Coastal Virginia,

and one per (50) worked in the Valley and Western Virginia. A review of job listings posted online by data

center operators shows active job openings in all four regions of the state. Data center employment should

continue to increase throughout the state into the future.

Additionally, we estimate that the accumulated capital investment in data centers across the state

amounts to $126 billion in 2021 dollars. We estimate that Virginia data centers spent $5.4 billion in 2021 for

operational expenses, the majority of which was spent for stang and power.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 12

The Impact of Data Centers on Virginia State and

Local Economies

The construction and ongoing operation of data centers in Virginia have large, broad eects across the state

economy. In this section, we estimate the statewide economic impact that data centers have on Virginia,

as well as in each of the four sub-state regions detailed earlier. To empirically evaluate the statewide and

regional economic impact attributable to data centers, we employ a commonly used regional economic

impact model called IMPLAN.

20

Regional economic impact modeling measures the ripple eects that an expenditure generates as it makes

its way through the economy. Spending by data centers in Virginia has a direct economic impact on the

state and regional economy in terms of people hired as data center employees, employee pay and benets,

and economic activity in the region for utilities, construction, and equipment. That direct spending by the

data centers creates the rst ripple of economic activity.

As data center employees and businesses (like construction contractors for data centers, power companies

that supply data centers, and data center equipment suppliers) spend the money that they were paid by

data center companies, they create another indirect ripple of economic activity that is part of the second-

round eects of data center activity.

In addition to the economic eects in the Virginia state and local economies of the data center-to-other

business transactions, there are also the second-round economic eects associated with data center

employee-to-business transactions that ripple through local economies. These eects occur when data

center employees buy groceries; pay rent; go out for dinner, entertainment, or other recreation; pay for

schooling in Virginia; or make other local purchases. Additionally, there are the second-round economic

eects of business-to-business transactions between the direct vendors to data centers and their suppliers.

The total impact is simply the sum of the rst round direct and second round impacts. These categories of

impact are then further dened in terms of employment (the jobs that are created), labor income (the pay

and benets associated with those jobs), and economic output (the total amount of economic activity that is

created in the economy).

20

IMPLAN is produced by IMPLAN Group, LLC.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 13

Table 1: Some Businesses Serving Virginia Data Centers

There are many Virginia businesses that are part of the data center supply chain. To illustrate some of the

types of companies located in Virginia that benet from data centers in Virginia and that, in turn, generate

economic activity in the state, in Table 1 we list a few dierent types of businesses in the Virginia data

center supply chain. The list of businesses in Table 1 is not an endorsement, promotion, or commendation

of them, and it is far from a complete list of companies. We only provide it to illustrate some of the types of

businesses that are part of the second ripple eect of economic activity related to spending by data centers.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

14

Virginia Statewide

We estimate that in 2021 data centers in Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 5,550 operational jobs and 10,230 construction and manufacturing jobs

• $1.6 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $7.5 billion in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the total

impact on Virginia from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 45,460 supported jobs

• $3.6 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $15.3 billion in economic output.

For every job inside a Virginia data center, there are 4.1 additional jobs that are supported in the rest of

the Virginia economy, not counting construction jobs.

Table 2: Economic Impact of Data Centers in Virginia in 2021

Because of the large amount of data center development in Virginia over the last several years, parts of the

data center construction and operations supply chains (illustrated in Table 1) have developed in the state.

This is why data center development in one part of the state creates impacts in other parts of the state. In

the following sections covering the four regions of the state, we show the local impacts of direct investment

in a region from the construction and operation of data centers. We also show the impacts in each region

caused by data center development in other regions.

So, for example, the 9,680 construction jobs building data centers in Northern Virginia supported 5,330 jobs

in other industries in Northern Virginia, as well as supporting 380 jobs in Central and Coastal Virginia, 30 jobs

in Southern Virginia, and 540 jobs in the Valley and Western Virginia. Likewise, the 4,920 operational jobs

in Northern Virginia data centers supported 19,140 jobs in other industries in Northern Virginia, as well as

supporting 1,030 in Central and Coastal Virginia, 20 jobs in Southern Virginia, and 60 jobs in the Valley and

Western Virginia.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 15

Central and Coastal Virginia

We estimate that in 2021, data centers in Central and Coastal Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 250 operational jobs and 290 construction jobs

• $41 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $289 million in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the total

impact on Central and Coastal Virginia from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 3,640 supported jobs (including 1,650 supported data centers in other parts of the state)

• $244 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $1.1 billion in economic output.

Table 3: Economic Impact of Data Centers on Central and Coastal Virginia in 2021

Investment Highlight - Community Action Grants

Meta (formerly dba Facebook) has a Community Action Grants program to fund non-prot projects that

meet community needs by deploying technology to benet the community, build stronger online and

oine connections among people, and improve local science, technology, engineering, and mathematics

education. In 2021, the program provided funding for eight projects including buying laptop computers for

local 10th graders, funding Henrico County Public Library’s WiFi lending program, buying video equipment

for children with illnesses, and supporting a telehealth program for underserved students and families.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 16

Northern Virginia

We estimate that in 2021, data centers in Northern Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 4,920 operational jobs and 9,680 construction jobs

• $1.5 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $7 billion in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the total

impact on Northern Virginia from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 39,230 supported jobs (including 160 supported data centers in other parts of the state)

• $3.3 billion in associated employee pay and benets

• $13.5 billion in economic output

Table 4: Economic Impact of Data Centers on Northern Virginia in 2021

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Investment Highlight - The Northern Virginia Community College Programs

Northern Virginia Community College (NOVA) has developed programs to help address the challenges that

data centers in the Northern Virginia area have meeting their stang needs. Amazon Web Services (AWS)

has a paid apprenticeship program at the NOVA.

21

In December 2018, the program graduated its rst

students into full-time Associate Cloud Consultant jobs with AWS.

NOVA also has a 2-year Associate of Applied Science program to train Datacenter Operations Technicians.

22

The program includes lab training at a training data center that the State of Virginia built on the

NOVA Loudoun Campus. The program started with 19 students in its very rst year, and enrollment has

increased signicantly since then. Graduates quickly nd jobs in Northern Virginia data centers and the

companies that work for them.

Investment Highlight - New Data Center Expansions in Fairfax County

Data center investment in Fairfax County has increased signicantly in the past two years. Data centers in

Fairfax County currently occupy 2.4 million square feet in 28 facilities. As of February 2022, the pipeline

of new data center development includes 1.9 million square feet, with 375,000 square feet already under

construction. Fairfax County has development opportunities available in both greeneld areas near Dulles

International Airport and inll locations in Tysons Corner.

NOVA, “Amazon and Northern Virginia Community College Announce Graduation of the First Veteran Technical Apprenticeship

Cohort on the East Coast,” December , .

NOVA - Catalog, Engineering Technology: Data Center Operations Specialization, A.A.

17

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 18

Southern Virginia

We estimate that in 2021, data centers in Southern Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 330 operational jobs and 260 construction jobs

• $39 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $215 million in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the total

impact on Southern Virginia from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 1,400 supported jobs (including 60 supported by data centers in other parts of the state)

• $73 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $402 million in economic output

Table 5: Economic Impact of Data Centers on Southern Virginia in 2021

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Investment Highlight - SOVA Innovation Hub

Mid-Atlantic Broadband Communities Corporation and Microsoft TechSpark are investing in Southern

Virginia, in part, by jointly creating the SOVA Innovation Hub in South Boston to oer programs to inspire

entrepreneurship and the pursuit of digital careers. The new building houses coworking, meeting, and

training space. Training programs are oered for job seekers, educators, families, and businesses. The

Hub has assisted a broad range of businesses, from the arts, to driver training, marketing, and organic

horticulture.

Microsoft’s Southern Virginia TechSpark is a civic program created to foster job creation and economic

development in the area. In addition to the innovation hub, TechSpark has helped to create technology

education and literacy programs in every high school in the region, “Girls Who Code” clubs in Halifax and

Mecklenburg Counties, and the deployment of free public WiFi networks Boydton and Clarksville.

23

Miranda Baines, “Microsoft TechSpark Celebrates Third Anniversary,” Gazette-Virginian, December , .

19

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

20

Valley and Western Virginia

We estimate that in 2021, data centers in the Valley and Western Virginia directly provided approximately:

• 50 operational jobs

• $7 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $47 million in economic output

Taking into account the economic ripple eects generated by that direct impact, we estimate that the total

impact on the Valley and Western Virginia from data centers in 2021 was approximately:

• 1,190 supported jobs (including 950 supported by data centers in other parts of the state)

• $59 million in associated employee pay and benets

• $253 million in economic output

Table 6: Economic Impact of Data Centers on the Valley and Western Virginia in 2021

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Investment Highlight - Project Oasis and Mineral Gap

Part of the InvestSWVA public-private partnership is Project Oasis – a program to attract data centers to

Southwest Virginia. The program emphasizes the ability of the area to assist data centers locating in the

area to achieve their sustainability goals by taking advantage of the region’s solar farms and availability for

geothermal cooling.

The DP Facilities data center in Mineral Gap (Wise County) oers a high-security, 65,000 square foot facility

in a reclaimed mine site with N+2 redundancy, 45 MW of power capacity, and an estimated power usage

eectiveness of 1.2. The 22-acre site has room to expand by an additional 200,000 square feet. An on-site

solar facility provides 3.5 MW of power for the data center. The $4.6 million solar project is the rst solar

project in the state to be built on reclaimed mine land.

21

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

22

Data Centers’ Contribution to State and Local

Government Budgets

Data centers pay millions of dollars in state and local taxes in Virginia, even though Virginia has a sales and

use tax exemption on some equipment for data centers that are large enough to qualify for the exemption.

All data centers (large and small) pay state employer withholding taxes. At the local level, both large and

small data centers pay real estate taxes, tangible personal property taxes, business license taxes, and

industrial utilities taxes. Additionally, many data centers still must pay state sales and use taxes on their

purchases of data center equipment because they are not large enough to qualify for the Virginia data

center incentive.

In addition to the taxes that data centers pay directly, the economic activity that they generate also results

in additional tax collections. Data centers pay taxes directly to state and local governments. The employees

and business suppliers that are paid directly by the data centers also pay taxes. All of these sources of tax

revenue are included in the tax revenue estimates described in this report

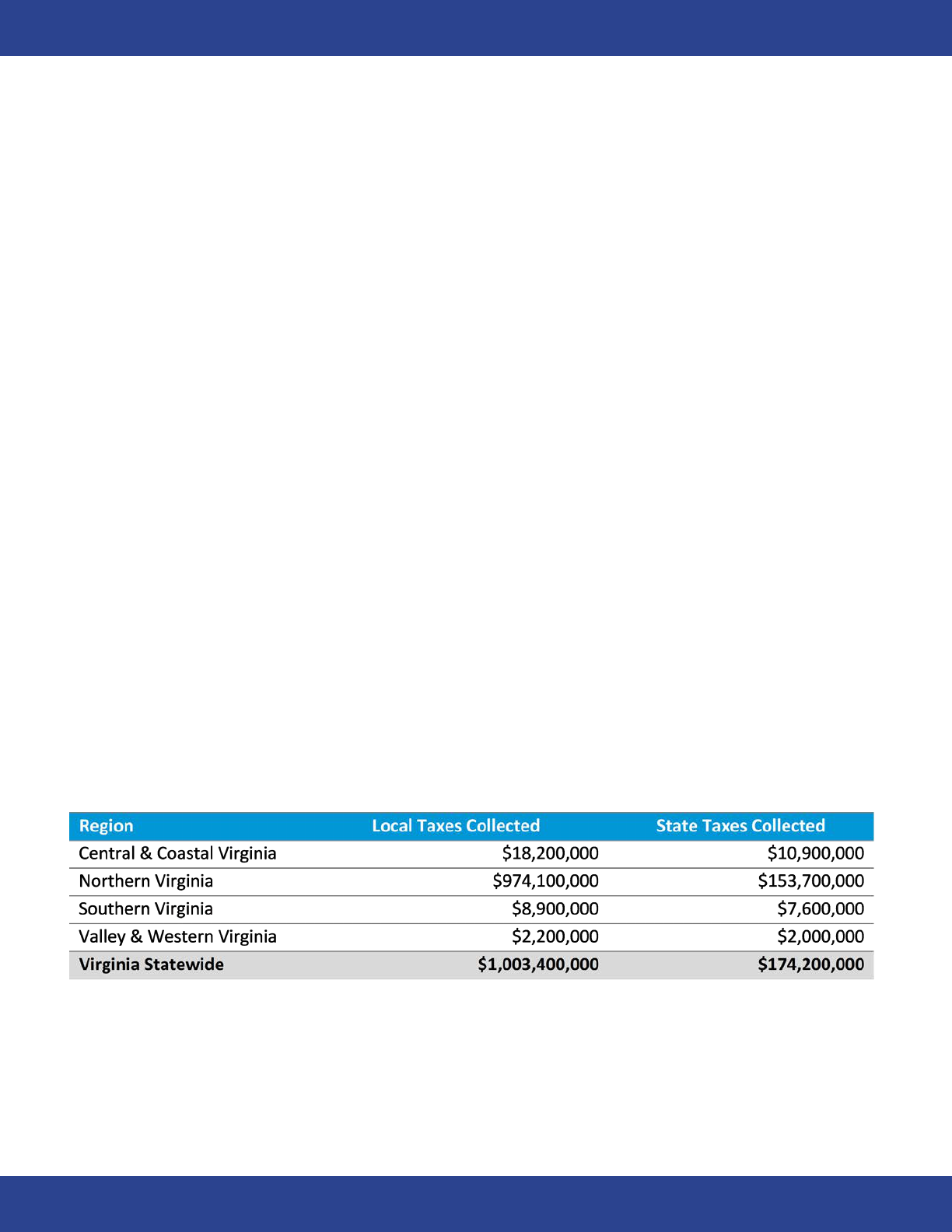

Statewide and Regional Tax Collections Associated with Data Centers

In addition to the taxes paid directly by data centers, local governments and the Commonwealth of Virginia

collect tax revenue from the secondary indirect and induced economic activity that data centers generate.

Table 7 shows our estimates of the taxes directly and indirectly generated by data centers statewide in

Virginia and in each of the four sub-state regions in 2021 through that rst round and second round

economic activity.

We estimate that in 2021, data centers were directly and indirectly responsible for generating $174

million in state revenue and $1 billion local tax revenue in Virginia.

Table 7: Tax Revenue Directly and Indirectly Generated by Data Centers in Virginia in 2021

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

23

Data Centers Contribute to Local Government Budgets

Data centers generate a large amount of property tax revenue for local governments without placing many

demands on local government services. Additionally, the industry also places downward pressure on overall

tax rates, thereby improving the locality’s business climate and economic attractiveness.

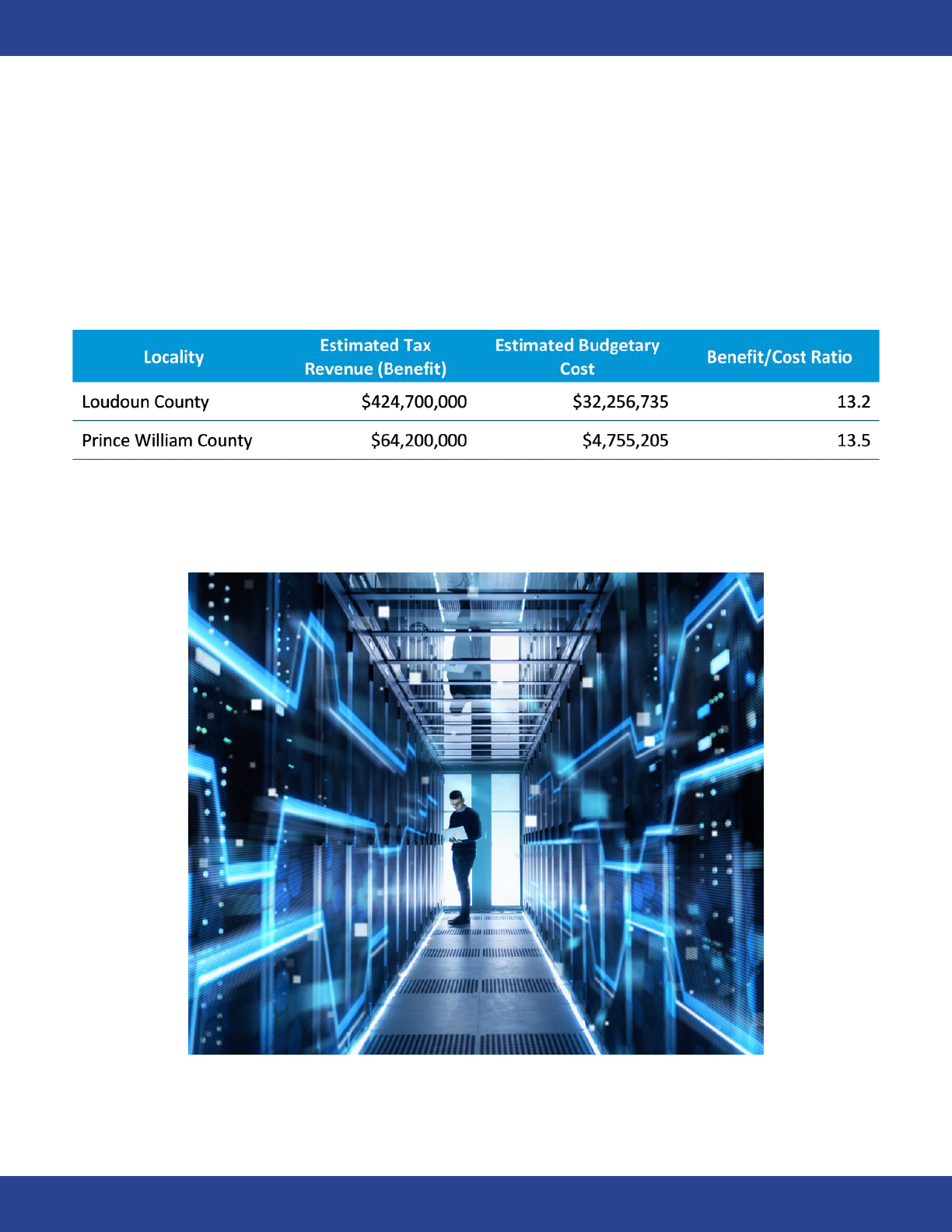

Data Centers’ High Local Benet to Cost Ratio

Data centers provide a high benet to cost ratio in terms of the tax revenue they generate relative to the

government services that they and their employees require. Loudoun and Prince William Counties are home

to the most signicant concentrations of data centers in Virginia. County sta in those localities were able

to provide us with detailed data on the tax revenue generated by this industry in each locality from real and

business personal property taxes.

24

As a result, we are able to use those data in combination with data from

other sources to compute the benet to cost ratio associated with data centers in each locality. If local scal

data were available, similar stories could be told for Mecklenburg and Henrico Counties where there are

larger data centers, and to a lesser degree in places like the Cities of Harrisonburg and Virginia Beach, and

Albemarle, Culpeper, Fairfax, and Wise Counties which also have data centers.

To quantify the budgetary cost that data centers and their employees imposed on these localities in

2020,

25

we use data from the Virginia Department of Education on local elementary and secondary

education expenditures per student, and data from the Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts on local non-

education expenditures per county resident. This approach focuses on the largest costs that any business

imposes on a local government – the costs associated with providing primary and secondary education, and

other county services, to the employees of that business.

It should be noted that, of necessity, these estimates exclude BPOL and other local taxes that also apply to data centers. As a

result, the revenue estimates provided almost certainly under-estimate the actual local tax revenues from data centers.

was the most recent year that data was available for these calculations.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 24

Table 8 details the calculations used to estimate the budgetary cost that data centers and their employees

imposed on each of these two counties in 2020. As shown, we estimate those costs to be approximately

$37 million in Loudoun County, and $5 million in Prince William County.

Table 8: Estimate of Total Budgetary Costs Imposed by Data Centers and Employees in 2020

Data Source: Loudoun County Economic Development Authority and Prince William County Department of Economic

Development.

Data Source: Virginia Department of Education and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Derived by dividing total county elementary

and secondary school enrollment in by total county employment in .

Data Source: Virginia Department of Education.

Calculated as county private sector employment in data centers in , times students per employee, times per student

education expenditures.

Data Source: Census and U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics. Calculated by dividing total county population in by total

county employment in .

Data Source: Virginia Auditor of Public Accounts and U.S. Census Bureau. Derived by dividing total county non-educational

expenditures in by total county population in .

Derived as county private sector employment in data centers in , times county residents per employee, times per resident

non-education expenditures.

Derived as the sum of total education costs and total non-education costs.

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

25

Table 9: Estimated Benet/Cost Ratio Associated with Data Centers and Employees in 2020

As shown in Table 9, combining the estimates of budgetary cost from Table 8 with data from each of

the localities on the local revenue generated by data centers shows that in 2020 the benet to cost ratio

associated with the industry was:

• 13.2 in Loudoun County — which means that for every $1.00 in county expenditures that data centers

were responsible for generating in 2020, it provided approximately $13.20 in tax revenue.

• 13.5 in Prince William County — which means that for every $1.00 in county expenditures that data

centers were responsible for generating in 2020, it provided approximately $13.50 in tax revenue.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Local Data Centers Reduce the Burden on the State Education Budget

Because of the way that the State of Virginia partially funds local education from State coers, the tax

revenue generated by data centers in some localities reduces the burden on the State education budget.

On average, the state of Virginia funds 55% of primary and secondary education expenditures, and localities

are required to locally fund the remaining 45%.

34

But, that local funding percentage is adjusted up or

down based on each locality’s “ability to pay” as measured by Virginia’s composite index formula that takes

into account the locality’s property tax base, adjusted gross income, and taxable retail sales. Of these three

factors, property tax base receives the highest weight (50%) and, therefore, has the largest inuence on the

nal calculation.

35

The 2020 composite index for Loudoun County is 0.5450 and for Prince William County it is 0.3739.

36

When

we recalculate those indices to take into account the loss of tax base implied by the loss in tax revenue

that would have occurred if data centers had not existed in these localities, those indices fall to 0.5026 and

0.3609, respectively.

As shown in Table 10, according to our estimates, this means that in the absence of data centers in Loudoun

and Prince William Counties, the State of Virginia would have to reallocate $90.5 million in state education

funding away from other Virginia localities to provide $73 million in additional funding to Loudoun County,

and $17.5 million in additional funding to Prince William County.

In actuality, however, baseline local funding percentages are typically higher than % because of local initiatives.

Virginia Department of Education. The actual formula weights each locality’s property tax base by ., adjusted gross income

by ., and taxable retail sales by .. Each metric is then divided by school population and total population and those per capita

figures are divided by the average across all localities to determine ability to pay. The per capita figures are then themselves

weighted with each per capita school population metric receiving a weight of . and each per capita population metric

receiving a weight of ..

Virginia Department of Education.

26

Table 10: Estimated Additional Revenue Required to Compensate for Loss of the Data Centers in 2020

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

27

Virginia’s data center incentive program is primarily a sales and use tax exemption on qualifying

equipment.

37

Generally, the sales and use tax exemption is available to data centers that make a minimum

new capital investment of $150 million and that create a minimum of 50 new jobs in a Virginia locality. If

the data center is located in an enterprise zone, the minimum new job requirement is reduced to 25. Each

new job must pay at least 150% of the annual average wage in the locality where the data center is located.

Tenants of colocation data centers that qualify for the incentive may also receive the sales and use tax

exemption. The incentive program is set to sunset in 2035.

In March of 2021, Virginia revised its sales and use tax exemption to require only 10 new employees and

$70 million of capital investment for data centers that locate where the unemployment and poverty rates

are higher than statewide averages.

38

According to the JLARC, as of scal year 2017 (the most recent year that data is available), 24 data centers

had qualied for the incentive, plus 135 colocation data center tenants.

39

According to JLARC’s 2021 report

on Virginia’s economic development incentives, in scal year 2020, $138.3 million of sales and use tax was

exempted under the incentive.

40

Virginia Treats Data Centers Like Other Capital-Intensive Industries

The Virginia data center incentive program oers qualifying data centers the same tax treatment that

it applies to all manufacturers. Like most states, Virginia exempts all manufacturing rms (regardless of

size) from paying sales and use tax on their production equipment. Part of the rationale for exempting

manufacturing equipment from sales and use tax is that the manufacturing industry requires large amounts

of expensive equipment in order to make products. If the state charged sales and use tax on manufacturing

equipment, manufacturers would locate in other states in order to reduce their costs of production. Virginia’s

sales and use tax exemption for qualifying data centers is a limited way to attract large data centers to

the state.

Virginia’s Data Center Sales and Use Tax Exemption

Virginia also offers a single sales factor apportionment method for calculating corporate tax liability. According to JLARC’s

report, that incentive was first used by data centers in and amounted to a change in taxes of only $,. Because this

incentive has such a limited impact, we do not discuss it in this report.

Dan Swinhoe, “Virginia lowers threshold for data center tax exemption,” Data Center Dynamics, March , .

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June , .

http://jlarc.virginia.gov/pdfs/reports/Rpt.pdf

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 28

JLARC’s Evaluation of the Data Center Incentive

In June of 2019, Virginia’s Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission published an evaluation of the

state’s data center incentive using condential tax information that is not publicly available.

41

JLARC found that 90% of the data center investment made by the companies that received the sales and

use tax exemption would not have occurred in the state of Virginia without the incentive. Instead, that

90% of data center investment would have occurred in states other than Virginia. So, the “cost” of the State

data center incentive is only 10% of the amount of State sales tax revenue exempted. Using the condential

tax information, JLARC estimated the economic and government budgetary impact, not of the total data

center industry in Virginia (as we have done in this report), but specically of Virginia’s data center sales and

use tax exemption.

42

Table 11 shows the text of Appendix N from the JLARC report with JLARC’s calculations of the amount

of State tax revenue exempted by the Virginia incentive; the amount of additional State tax revenue that

was generated by the investment of the data centers that received the tax incentive; the net impact of

the incentive on the State budget (additional tax received minus tax revenue exempted); net new jobs

added, net additional state gross domestic product (GDP) generated, and net new worker pay generated

throughout the statewide economy as a result of the investment by data centers that received the incentive.

Table 11 shows data for the scal years 2013 through 2017. This is the most recent data available that covers

the years when the current version of Virginia’s data center incentive has been implemented. The General

Assembly made signicant revisions to the data center incentive in 2012.

Joint Legislative Audit and Review Commission, Data Center and Manufacturing Incentives, Economic Development Incentives

Evaluation Series. June , .

Appendix N: Results of economic and revenue impact analyses.

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 29

Table 11: Economic and Tax Impacts of Virginia’s Sales and Use Tax Exemption for Data Centers

43

The appendix to the JLARC report shows that:

• In 2017, the State took in $1.09 in state tax revenue from data center related activity for every $1 of

potential state tax revenue that was exempted from qualifying data centers.

• In 2016, the data center incentive was revenue neutral – it generated one dollar in additional state tax

revenue for every dollar of potential state tax revenue that it exempted.

• In every year since the data center incentive was modied in 2012, the State recovered the majority of

the state tax revenue that was exempted from qualifying data centers.

• From 2013 through 2017, on average the State recovered 75 cents in state tax revenue for every dollar of

potential tax revenue exempted from qualifying data centers.

44

Data Source: Appendix N: Results of Economic and Revenue Impact Analyses.

The JLARC report states that the data center incentive recovered cents in state tax revenue for every dollar of potential tax

revenue exempted from qualifying data centers. That conclusion is based on including the years through , prior to the

significant change made to the incentive in . The -cent estimate more accurately reflects

2022 Virginia Data Center Report 30

Incentive Helps to Attract Some Data Centers that Do Not Qualify for Incentive

Data centers tend to cluster, with smaller data centers often locating adjacent to larger data centers.

Therefore, one data center that is attracted by the incentive can attract other data centers to take advantage

of the existing local ber and power infrastructure.

45

Some of these follow-on data centers will be smaller

than the larger data center projects that qualied for the tax incentive and may, themselves, not initially

achieve the investment and job creation thresholds required to receive tax benet from the state.

Because large data centers that qualify for Virginia’s incentive help provide the infrastructure and technology

supply chain to attract smaller data centers that do not initially qualify for the incentive, the incentive

yields more data center investment than is measured by just counting the data centers that qualify for the

incentive. Virginia’s data center tax incentive plays an important role in attracting new data centers to the

state and in keeping them from moving to other states.

National Context for Virginia Incentives

Over 30 states oer some sort of incentive program to attract data centers. Twenty-six states have sales and

use tax incentives that last for 10 years or more, with 11 of them having incentives that are valid indenitely.

Examples in the Southeast include:

• Alabama oers up to a 30-year sales and use tax exemption. (AL 40-9B-3)

46

• Mississippi’s 10-year sales and use tax exemption has no program sunset. (MS 57-113-25)

47

• North Carolina’s sales and use tax exemption has no program sunset. (NC 105-164.13)

48

• South Carolina’s sales and use tax exemption sunsets for new applicants in 2031 with benets ending in

2041. (SC 12-36-2120)

49

• Tennessee’s sales and use tax exemption and reduced tax on electricity has no program sunset.

(TN 67-6-206)

50

In the last few years several states have added or expanded sales and use tax exemptions for data centers.

The following list does not include states like Ohio and Texas which have robust incentives in place.

Loudon Blair, “Finding Strength in Numbers: The Data Center Clustering Effect,” Data Center Knowledge,

http://alisondb.legislature.state.al.us/alison/CodeOfAlabama//.htm and Alabama Department of Revenue, General

Summary of State Taxes.

Mississippi Tax Incentives, Exemptions and Credits.

North Carolina Data Center Sales and Use Tax Exemptions.

South Carolina Department of Revenue Ruling #-.

Changes in Requirements for a Qualified Data Center, Tennessee Department of Revenue.

Pennsylvania Brings in Data Center Tax Breaks.

Matt Pilon, “In a crowded pond, CT goes fishing for data centers with new incentives,” Hartford Business Journal, April , .

Maryland Department of Commerce, Data Center Tax Incentive Program.

Rich Miller, “Quantum Loophole Plans , Acre Data Center Campus in Maryland,” Data Center Frontier, June , .

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

31

East

• Pennsylvania’s original incentive was ineective at attracting data center investment to the state while

billions of dollars of investments were being made in nearby states. The legislature enacted a new sales

and use tax exemption that is open indenitely with benets available for at least 15 years.

(72 PS 9931-D)

51

• Connecticut became the latest state to add a completely new data center incentive. Depending on the

size and location of the facility, data centers could be exempted from state sales and use taxes for 20 to

30 years. (CT Public Act 21-1, HB 6514)

52

• Maryland enacted a new sales and use tax incentive with a benet period of 10 to 20 years depending on

the level of investment. The incentive has no sunset date.

53

Following the enactment of Maryland’s data

center incentive, a data center developer announced plans for a new 2,100-acre data center campus in

the state. (MD 11-239)

54

Midwest

• North Dakota enacted a data center incentive to replace an incentive that expired in 2020. The new

incentive has no sunset date or limitation on the benet period. (NDCC 57-39.2-04.17)

55

West

• Arizona revised and extended its data center sales and use tax exemption by 10 years to run through

2033. The benet period ranges from 10 to 20 years, with the 20-year benet reserved for data centers

with that are considered a sustainable redevelopment project. (AZ 41-1519)

56

• Idaho enacted a new sales and use tax exemption for data center equipment used in new data centers.

The new incentive has no program sunset or limitation on the benet period. (63-3622V)

57

• Utah expanded its sales and use tax exemption for data centers with no minimum investment or

employment criteria and no program sunset. (UT 59-12-104)

58

North Dakota Century Code § -.-..

Dan Swinhoe, “Arizona extends data center tax breaks for another years,” Data Center Dynamics, April , .

HB .

Utah Sales and Use Tax General Information, Revised / and SB .

2022 Virginia Data Center Report

Competition Between States

With so many states oering incentives to attract data centers to their states, the competition for data

centers is keen.

New York - New Jersey - Connecticut

New Jersey is debating adding an incentive. There is a growing realization that the New York-New Jersey

region lost its lead in the data center market to Northern Virginia, at least in part because New Jersey is not

competitive with other markets on taxes.

59

An even more dramatic illustration of the sensitivity of data centers to tax changes is the way in which data

centers showed their mobility in response to a potential increase in taxes in New Jersey. In the summer of

2020, some elected state ocials proposed imposing a 25/100th of one percent or a 1/100th of one percent

tax on nancial transactions processed in data centers located in New Jersey.

60

In the fall of 2020, the New

York Stock Exchange ran its nancial transactions out of its data center in Chicago for ve days to practice

for any possible relocation of the market to data centers outside of New Jersey. The Governor of Texas was

involved in attempting to attract Nasdaq to migrate its data center operations to Dallas, the second-largest

data center market in the United States. In the spring of 2021, the state of Connecticut enacted a data center

incentive to make that state a viable alternative, in the event that New Jersey proceeded with the nancial

transaction tax.

61

Illinois - Indiana

In June of 2019, Illinois added a new data center incentive.

62

Although the Chicago area is one of the

largest data center markets in the United States, it was not keeping pace with the growth of data centers

in the markets of Northern Virginia, Dallas, and Phoenix – all located in states that provide sales and use

tax exemptions to attract data center investment. Since the enactment of the Illinois incentive, several new

large data center projects have been announced in the state, and over $5 billion in additional data center

investment has been committed, making it one of the fastest-growing states in terms of data center

activity.

63

The neighboring state of Indiana also enacted a 50-year sales and use tax exemption for data

centers to attract data centers to the Indiana suburbs of Chicago.

“Twenty years ago, New Jersey probably led the country and data center space, but we haven’t moved the needle at all in

years.” – Gil Santaliz, NJFX “New Jersey was once a hotbed of data center activity, with thriving markets for colocation and financial

data centers. The state maintains a substantial and strategically important data center community, but the hottest leasing action

has shifted elsewhere, primarily to Northern Virginia.” – Data Center Frontier, // “There is a bill being looked at, and it looks

very similar to the broad strokes of what you see in Virginia.” – Santaliz

Alex Alley, “NYSE and Nasdaq threaten to leave New Jersey if transaction tax goes ahead,” Data Center Dynamics, October ,

.

Matt Pilon, “In a crowded pond, CT goes fishing for data centers with new incentives,” Hartford Business Journal, April , .

Ally Marotti. “Data center boosters hope new tax incentives 'stop the bleeding,' keep tech sites in Illinois,” Chicago Tribune, June

.

Companies announcing large data center projects in Illinois since the enactment of the incentive include: Aligned Energy, Meta,

Prime Data Centers, NTT, and Stream.

32