International

Education Services

Productivity Commission

Research Paper

April 2015

Commonwealth of Australia 2015

ISBN 978-1-74037-546-7 (PDF)

ISBN 978-1-74037-547-4 (Print)

Except for the Commonwealth Coat of Arms and content supplied by third parties, this copyright work is

licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence. To view a copy of this licence, visit

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/au

. In essence, you are free to copy, communicate and adapt the

work, as long as you attribute the work to the Productivity Commission (but not in any way that suggests the

Commission endorses you or your use) and abide by the other licence terms.

Use of the Commonwealth Coat of Arms

For terms of use of the Coat of Arms visit the ‘It’s an Honour’ website: http://www.itsanhonour.gov.au

Third party copyright

Wherever a third party holds copyright in this material, the copyright remains with that party. Their

permission may be required to use the material, please contact them directly.

Attribution

This work should be attributed as follows, Source: Productivity Commission, International Education

Services.

If you have adapted, modified or transformed this work in anyway, please use the following, Source: based

on Productivity Commission data, International Education Services.

An appropriate reference for this publication is:

Productivity Commission 2015, International Education Services, Commission Research Paper, Canberra.

Publications enquiries

Media and Publications, phone: (03) 9653 2244 or email: maps@pc.gov.au

The Productivity Commission

The Productivity Commission is the Australian Government’s independent research and

advisory body on a range of economic, social and environmental issues affecting the welfare of

Australians. Its role, expressed most simply, is to help governments make better policies, in the

long term interest of the Australian community.

The Commission’s independence is underpinned by an Act of Parliament. Its processes and

outputs are open to public scrutiny and are driven by concern for the wellbeing of the

community as a whole.

Further information on the Productivity Commission can be obtained from the Commission’s

website (www.pc.gov.au).

CONTENTS

iii

Contents

Acknowledgments v

Overview 1

International education services are important to the economy 3

Government involvement in international education 6

Swings in visa policy settings 9

Quality regulation is a ‘work in progress’ 13

Alternative frameworks for student visa processing 16

The use of education agents is extensive and risky 19

1

Introduction 21

1.1 The international education sector’s contribution to the

economy 21

1.2 Snapshot of the international education services sector 24

1.3 International education policy levers 28

1.4 The Commission’s approach 33

2 Trends in international education services 35

2.1 Global trends in international education services 36

2.2 Trends in Australian international education services 47

3 Student visa policy settings 63

3.1 The student visa program 64

3.2 Implications of Streamlined Visa Processing 75

3.3 Post-study work rights 90

4 Quality regulation of international education services 99

4.1 Regulatory framework for quality assurance 100

4.2 Risks to quality and how they are being addressed 109

4.3 Transnational education services 121

4.4 Measuring the quality of international education services 123

iv

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

5 Student visa processing alternatives 125

5.1 Summary of the current problems 126

5.2 DIBP’s proposed model 127

5.3 Alternative approaches 130

6 Education agents 133

6.1 Education agents in international student recruitment 133

6.2 Institutional arrangements around agents 136

6.3 Concerns with agent behaviour 138

6.4 Risks arise from the incentives faced by agents and

providers 141

6.5 Mitigating agent risk 143

A Conduct of the project 149

References 151

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

v

Acknowledgments

The Commission is grateful to everyone who has taken the time to discuss the issues

canvassed in this research project. Particular thanks are extended to those who participated

in the Commission’s roundtable held in Melbourne on 4 December 2014, and provided

written comments.

The Commission would also like to thank officers of the Department of Immigration and

Border Protection, the Department of Education and Training, the Department of

Employment, the Australian Skills Quality Authority and the Tertiary Education Quality

Standards Agency for their high level of engagement and the provision of data and

information.

Paul Lindwall

Commissioner

30 April 2015

OVERVIEW

2

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Key points

• International students make a major economic and social contribution to Australia. In 2014,

there were over 450 000 international students onshore, representing around 20 per cent of

higher education students and 5 per cent of students enrolled in vocational education and

training.

– The international education sector is back on a high-growth trajectory following a major

downturn from 2009 to 2011. Students from China and India account for 37 per cent of all

international students in Australia.

•

In parallel with rapidly growing demand for international education, principally from

middle-income economies in Asia, competition for international students is intensifying among

traditional provider countries and new entrants. While Australia’s share of the international

student market is only around 6 per cent, it has one of the highest concentrations of

international students in total national tertiary enrolments.

• Whether Australia remains an attractive destination will depend on how well education

providers respond to students’ expectations for their learning experience and provide a value

proposition as technology and business models evolve.

• The Australian Government has a role in providing a policy and regulatory framework that

encourages behaviours by education providers, international students and other stakeholders

that support its immigration and education policy objectives, and enables the market for

international education services to function well within these policy settings.

– The sustainability of international education exports is more closely linked to regulatory

settings than in many other sectors

. Regulatory settings around student visas and

education quality are crucial.

– The lack of a synchronised and coherent strategy for these two interacting policy levers

has the potential to undermine the sector’s ability to take advantage of the opportunities

offered by growth in the global education market.

• In terms of student visas, the introduction of streamlined visa processing has contributed to a

reversal of the downward trend in international student numbers, with the higher education

sector as the predominant beneficiary. However, the implementation o

f this system has

introduced a number of perverse incentives that put at risk the quality and reputation of

Australia’s education systems.

• The potential broadening of access to streamlined visa processing by a wider spectrum of

education providers carries risks to the reputation of Australia’s education system.

– There are several options to mitigate these risks. The preferred option should provide the

highest net benefit to Australia as a whole. But they all require a high level of engagement

between the Department of Immigration and Border Protection and the Department of

Education and Training.

• In terms of education quality, the enforcement of regulatory settings has moved increasingly

to a risk-based approach in recent years. However, the current emphasi

s on teaching

standards should be rebalanced so that learning standards have a greater role in quality

assurance.

• There is also a strong case for publicly available information on the comparative quality

ranking of providers in order to assist domestic and international students to make informed

decisions about provider choice.

• Further, Australian institutions should reduce their reliance on agents for student recruitment.

OVERVIEW

3

Overview

International education services are important to the

economy

The global market for education services is expanding as incomes and participation in

education in emerging economies continue to rise. Australia is an attractive destination for

international students at all levels of education. There is also a high demand for Australian

education providers delivering courses abroad.

In 2014, international education services (IES) contributed around $17 billion to the

Australian economy. Around half of this was from the fees paid to educational institutions,

with the remainder from expenditure on goods and services by international students living

in Australia. The sector represented around 27 per cent of services exports and close to

5 per cent of total Australian exports.

There were over 450 000 international students on a student visa in Australia in 2014.

International students accounted for around 20 per cent of students enrolled in higher

education and around 5 per cent of students enrolled in vocational education and training

(VET). Around three quarters of all international students enrolled in Australia in 2014

were from Asia, with China and India accounting for 26 and 11 per cent of all international

students respectively (figure 1, panel a). Of the 160 000 enrolments in courses delivered

offshore, more than two thirds were in the higher education sector.

Students enrolled in higher education provided the greatest economic contribution

(68 per cent of the value of education exports). New South Wales ($5.8 billion) and

Victoria ($4.7 billion) generated the highest export income from the sector.

The sector is back on a high-growth trajectory

Following a period of rapid growth in the international education sector from 2007 to

2009 — partly driven by the direct pathway from the student visa program to permanent

skilled migration — the sector experienced a major downturn from 2009 to 2011. The high

Australian dollar, the global economic downturn, the introduction of a series of visa

integrity measures, negative publicity about student safety in Australia, and uncertainty

about college closures were key contributing factors.

The sector has since recovered from this decline and is back on a high-growth trajectory

(figure 1, panel b). In 2014, the number of international students in Australia increased by

more than 10 per cent on 2013 levels and education-related exports also grew by a similar

4

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

rate. However, this growth has been uneven across the sector. Over the period from 2012

(when streamlined visa processing (SVP) was introduced) to 2014, the Commission

estimates the average annual growth rate in the number of international students was

4.6 per cent in higher education, 2.9 per cent in VET, 11.8 per cent in intensive English

language courses (a major study pathway to higher education and VET), with a marginal

fall in the growth rate in school enrolments.

A number of factors contributed to this rebound. These include the introduction of an

expansionary student visa policy through SVP, post study work rights, and improved

economic conditions following the global financial crisis.

The changing playing field is intensifying competitive pressures

Various economic, demographic and social factors drive the mobility of students globally.

Some of the factors affecting the demand for IES are intertwined with those factors which

shape people’s decisions to migrate permanently — of which economic opportunity is a

prime motivator.

For international students primarily seeking an educational outcome rather than permanent

migration, key factors influencing where students choose to study include the reputation of

an education provider (and the quality of the learning experience they offer), tuition fees,

the cost of living, safety, lifestyle, the presence of support networks, visa policy settings

(including the time and cost in procuring a visa) and any associated work rights. The

rationale for studying overseas is multifaceted, and the relative weighting of these drivers

of student choice is contingent on individual circumstances and motivations.

From 2000 to 2012, the number of international students globally grew by more than

5 per cent a year on average. Most of this growth has come from middle income Asian

economies — notably China, and to a lesser extent India, South Korea and south-east

Asian countries. Growth in international student numbers has also been strong from other

middle income economies such as Brazil and Russia.

The four leading English-speaking destination countries — the US, the UK, Australia and

Canada — dominate the global market for the provision of IES, with market shares of 16,

13, 6 and 5 per cent respectively. While the US remains the top destination for

international students, Australia and the UK have the highest concentration of international

students in total national tertiary enrolments (18 per cent) (figure 1, panel c).

Tertiary institutions in English-speaking OECD countries have generally responded well to

the increased demand for international advanced degrees by research (principally

doctorates). However, the ratio of enrolments in advanced degrees by research to

enrolments in bachelor’s and master’s degree programs remains lower in Australia than in

comparable countries (figure 1, panel d).

OVERVIEW

5

Figure 1 A snapshot of the international education services sector

a. Student enrolments in Australia by source

country, 2014

b. Total onshore education exports

c. Number and percentage of international

tertiary student enrolments

a

d. International student enrolments as a

percentage of total tertiary enrolments

a

Bubble size reflects the share of international students in total national tertiary enrolment.

0

30

60

90

120

150

180

China

India

Vietnam

South Korea

Thailand

Brazil

Malaysia

Nepal

Indonesia

Pakistan

Thousands

Higher Education VET

Schools ELICOS

Non-award

0

5

10

15

20

25

30

35

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

Per cent

$ Billions

Total onshore education exports

Education as a proportion of total

services exports (RHS)

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

800

1998 2003 2008 2013

Thousands

US UK Australia Canada

0 20 40 60

2005

2012

2005

2012

2005

2012

2005

2012

2005

2012

Australia Canada NZ UK US

Advanced research programs

Bachelor's & master's degree programs

VET programs

6

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

In parallel with the growth in demand for international education, competition in the

provision of international education is increasing globally. Many of the ‘traditional’

providers of IES are extending their international reach through the delivery of courses

offshore, often in partnership with education providers in host countries or through

consultancies for a corporate clientele.

Further, many countries in Asia and in the Middle East are seeking to develop world-class

capacity in higher education and research, and are investing heavily in higher education

systems. Countries such as Singapore and Malaysia have a significant interest in

positioning themselves as regional hubs for higher education. China is also actively

engaged in improving the range and quality of its education services.

The digital economy is broadening the options available to those seeking an education with

an international orientation. Technological advances have enabled the growth of so-called

massive open online courses, as well as a wider range of teaching and study modes.

However, until these online offerings provide equivalent and recognised formal

qualifications, they will be likely to remain a part of an educational offering rather than a

substitute for traditional delivery modes.

Government involvement in international education

Government involvement in the IES sector is more ubiquitous than in many other sectors.

This occurs for a number of reasons. Government itself is involved in the delivery of these

services through the ownership of public education institutions.

More broadly, there are inherent features of that market that prevent it from operating

efficiently without government intervention. These include the information asymmetries

between providers and students, which prevent students from fully assessing the value of

the education services they are purchasing, and the scope for poor quality providers to taint

the reputation of all providers and/or adversely affect the perceived quality of Australian

qualifications.

Further, the flow of international students into Australia is of necessity subject to

immigration policy settings. The temporary migration and work rights afforded by

international education (via student visas) directly affects its attractiveness. Hence,

immigration policy directly affects the demand for international education services.

Further, while the supply of international education is an export business, the provision of

education to international students is largely a joint product with the provision of education

to domestic students; indeed, many institutions purportedly use international student fees to

cross-subsidise other activities such as research. To this extent, student visa policy settings

can affect the financial viability of domestic education (more so in some segments than

others) and can also affect (positively or negatively) the value of the qualifications of

domestic students.

OVERVIEW

7

International education is also a pathway to permanent migration. While student visa

policy settings should be set to achieve the desired short- and long-term immigration mix,

governments can come under pressure from the international education sector to take their

businesses into account. However, it is not the role of government to ensure a reliable

supply of international students for the sector. Rather, an important role of government is

to provide a stable and predictable policy and regulatory framework that supports

behavioural responses by education providers, international students and other players that

are consistent with broader immigration and education policy objectives, while enabling

the market for IES to function efficiently and effectively within these objectives.

More generally, policies related to domestic education, notably in regard to quality, will

spill over into the international education sector. The cost and quality of education services

are key considerations for most students when choosing an international education

provider. However, given the nature of education services and the information asymmetry

between providers and purchasers, it is not easy for students to ascertain the quality of

these services ex-ante. There is a role for government to support a regulatory regime that

provides publicly available information on the relative quality of education services

offered by providers, especially as poor quality providers can harm the reputation of other

providers in Australia.

1

Governments at different levels are also involved in promoting Australia (or particular

regions within Australia) as a destination for international education. Such marketing has

some ‘public good’ characteristics in that the benefits are able to be captured by any

education provider in that destination, and it is not possible to exclude providers that

benefit from the marketing but do not contribute to the costs.

While government involvement is motivated by a variety of factors, it is only warranted

when the benefits to the entire community from such intervention outweigh the costs of

that intervention.

The sector is interconnected and needs an integrated policy response

A key feature of Australia’s international education system is that it provides for study

pathways between the four subsectors — intensive English language courses, primary and

secondary schools, vocational education, and higher education by coursework and

research. Courses are delivered onshore, offshore and online, and by a mix of public and

private providers. Even though institutions offer programs across a wide spectrum of study

fields, more than half of all international students in both higher education and VET are

enrolled in business-related courses.

A range of agencies and regulators at different levels of government are involved in the

international education sector (figure 2). Australian Government agencies have distinct and

1

Self-regulation and the private provision of quality indicators also have a role, but are unlikely to supplant

the need for government regulation and supervision given the pervasive interactions across a range of

policy areas in IES.

8

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

separate responsibilities cutting across education, immigration, employment and

marketing, with limited incentives to look at the sector on an holistic basis. Decisions made

in one policy space have broader sectoral and economywide implications.

Further, the evidence base appears fragmented, with different datasets measuring different

aspects of the sector and no obvious platform to support a whole-of-government approach

to policy development and evaluation.

Figure 2 Policy and regulatory landscape for international education

services

The sector has been extensively reviewed over the past decade, including the Chaney

Review in 2013, which highlighted the urgent need to develop a more coordinated

government approach to international education in Australia. In addition, several relevant

reviews are currently underway, including reviews into SVP arrangements, border fees,

charges and taxes, and into the framework and effectiveness of the skilled migration and

temporary activity visa programs.

In April 2015, the Government released a Draft National Strategy for International

Education for consultation. It noted that the Government agreed with all the Chaney

Review recommendations, including those directed at developing better coordination of

Australian Skills Quality Authority

(ASQA)

Tertiary Education Quality

Standards Agency

(TEQSA)

Education Services for

Overseas Students Act

2000 (Cwlth)

National Code of Practice for Registration

Authorities and Providers of Education and

Training to Overseas Students 2007

Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS)

Higher education

+ foundation courses

+ ELICOS delivered by a registered

higher education provider or under an

entry arrangement with a higher

education provider

VET

providers

ELICOS providers

(except when

delivered by a school

or higher education

provider)

Schools

+ ELICOS and

foundation programs

when delivered in a

school

Students

Relevant

state

or territory

regulators

Legislation and

regulation specific

to IES

Registration

requirements

Regulators

Service providers

Purchasers

Education agents

Policy oversight

Department of

Education and

Training

(IES policy

development)

Department of

Immigration and

Border

Protection

(visa settings)

AusTrade

(marketing

and

promotion)

State and

territory

government

departments

Migration Regulations

1994

Department of

Employment

(labour market

outcomes)

OVERVIEW

9

policies and programs affecting international education. This ongoing process provides an

opportunity to develop a comprehensive and integrated policy response to the opportunities

and challenges facing the sector.

Swings in visa policy settings

Over time, visa policy settings have been reviewed and adjusted frequently — perhaps too

frequently. The impulses for change have been as disparate as reactions to crises, the desire

to smooth out the peaks and troughs in student numbers, and the intention to balance the

sustainable growth of the sector against the risks to the integrity of the immigration system

(and national security) associated with the intake of international students. The swings in

visa policy settings are partly symptomatic of the use of one policy lever — student visa

settings — to achieve multiple policy objectives.

Streamlined visa processing has created some perverse incentives

The stated objective of the student visa program is to support the growth of the

international education sector, while maintaining high levels of immigration integrity

(which is essentially about ensuring that international students are genuine in their

intention to complete a course of study and do not use the program primarily as a de facto

migration entry point). The requirements and restrictions attached to different visa

sub-classes should be designed to meet this objective in the most efficient way.

The most recent substantive shift in student visa policy settings was the introduction of

SVP in 2012, which originated from the Knight Review. Against a backdrop of falling

student enrolments, the review contained a series of measures to improve the

competitiveness of Australia’s universities in the global market for international students.

Essentially, SVP treats international students applying to higher education courses as

though they were from assessment level 1 (low immigration risk) countries, irrespective of

their country of citizenship (box 1).

SVP is seen by eligible institutions (mainly universities) to have been beneficial to them

and to their students — notably those from medium and high immigration risk countries.

Notwithstanding the range of factors that drive demand for international education, student

visa applications for higher education courses have increased by 33 per cent over the two

years following the introduction of SVP (figure 3). By comparison, student visa

applications for VET courses have fallen by 15 per cent over the same period.

10

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Figure 3 Student visa applications by source country

a. Higher education b. VET

The SVP framework has introduced a stratified system for student visa processing. Further,

it has created a perception that provider access to SVP is a ‘stamp of quality’. The

combination of these two factors has led to some perverse incentives for:

• agents — to channel international students into higher education pathways, regardless

of their aptitude or career aspiration. This has disadvantaged high-quality VET

providers

• some SVP-eligible providers — to adopt a relatively relaxed approach to immigration

risk management so that they can expand their student intake up to the point that does

not trigger a penalty by the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP)

• providers — to add advanced diplomas to their offering since the recent extension of

SVP to these courses, with potential downside risks to the quality of these courses

• some prospective students and education agents — to target institutions with access to

SVP initially, and once granted a student visa, to ‘course-hop’ to another institution

offering an easier or cheaper course, potentially undermining the integrity of the visa

system and imposing a financial impost on those institutions losing students to other

institutions.

The challenges inherent in monitoring agents’ conduct, and concerns raised by some

stakeholders about the effectiveness of enforcement of visa conditions, contribute to

reinforcing these incentives.

This is particularly relevant to the issue of course-hopping. Students can change courses

for a variety of reasons. It is therefore difficult to ascertain the prevalence of ‘illegitimate’

course-hopping given the often covert nature of this type of activity. However, enrolment

data on actual transfers from higher education courses to VET courses point to an increase

in those transfers since the introduction of SVP, both in absolute and relative terms

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

160

180

2005-06 2009-10 2013-14

Thousands

All other countries China India

SVP

0

20

40

60

80

100

120

140

2005-06 2009-10 2013-14

Thousands

All other countries China India

SVP

OVERVIEW

11

(figure 4), although recorded transfers are still a relatively low percentage of overall

student numbers. There is also anecdotal reporting of agents being openly and actively

involved in encouraging course-hopping by recruiting students already studying in

Australia for transfers to cheaper, shorter or lower quality courses.

Conversely, visa data on transfers from higher education student visas (subclass 573) to

VET student visas (subclass 572) show a relatively flat trend since the introduction of SVP

(figure 4). While it is unclear why the pictures from these two datasets differ, the

discrepancy is possibly broadly consistent with anecdotal evidence of under-reporting,

whereby students are breaching their visa conditions by transferring between higher

education and VET courses without applying for a new visa.

Box 1 What is streamlined visa processing?

Commencing on 24 March 2012, streamlined visa processing (SVP) created a separate ‘fast

track’ or ‘light touch’ visa processing pathway for international students applying to eligible

courses. In order to be eligible for SVP, students had to be enrolled in:

• a principal course of study for either an advanced diploma (since November 2014), a

bachelor’s degree, a master’s degree or a doctoral degree

– the principal course of study is provided by an eligible education provider (any institution

registered on the Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas

Students) and which offers courses at the advanced diploma level and above

• a course leading to a principal course of study provided by an SVP-eligible provider.

The SVP pathway is premised on education providers sharing the immigration risk attached to

student visas in exchange for simpler and faster visa processing at the institution’s level. All

applicants are still subject to basic requirements such as having health insurance and not being

a security or health risk. However, the Department of Immigration and Border Protection (DIBP)

essentially take the institution’s word that the student is suitable. In return, the institutions are

accountable for the visa outcomes of their students. The visa outcomes of these institutions are

reviewed regularly, and consistently poor outcomes can lead to a withdrawal of their eligibility

for SVP. The effectiveness of risk sharing under SVP depends on whether the threat of having

access to SVP withdrawn is credible.

If access to SVP is removed, institutions can still enrol international students, but they are

processed under the assessment level framework — the ‘traditional’ pathway for the

assessment of student visas, which usually takes longer and carries a more onerous regulatory

burden. Under that framework, assessment levels are specified from 1 to 3, with assessment

level 1 pertaining to low immigration risk passport holders, assessment level 2 — medium risk,

and assessment level 3 — high risk. Evidentiary requirements for visa applicants are aligned to

immigration risk, and the assessment is undertaken by the DIBP, taking into account rates of

visa refusal, cancellation and non-compliance.

12

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Figure 4 International student transfers from higher education to VET

The DIBP has recently conducted a number of information campaigns to encourage visa

compliance, in combination with regular discretionary processes for visa cancellations.

Nonetheless, the fact remains that the current configuration of the student visa processing

framework inherently provides an incentive to course-hop, particularly for international

students whose primary motivation may not be an educational outcome and who may not

be suited to higher education.

The jury is still out on post-study work rights

Many international students consider host country work experience to be an attractive

element of the overseas study ‘package’. In particular, they often see it as a potential

pathway to obtaining permanent residency or to enhance employment prospects in their

home country.

Changes to Temporary Graduate Visas in 2013 gave longer and less restrictive post-study

work rights to higher education graduates than to VET graduates — thereby creating two

distinct visa categories. These changes also came from the Knight Review, which argued

that the absence of clearly defined post-study work rights puts Australian universities at a

serious disadvantage against some of our major competitor countries.

Post-study work visas are far from uniform internationally, and Australia’s program differs

in several ways from those of other countries that provide comparable education services

(chapter 3).

Given that these changes were implemented in 2013, their impacts are yet to flow through

to the take-up of temporary graduate visas. It is therefore premature to assess the link

between the post-study work rights policy settings and labour market outcomes. In any

case, there is a general lack of data to inform an analysis of the impacts of the relatively

0

2000

4000

6000

8000

2008 2009 2010 2011 2012 2013 2014

Enrolment transfers from Higher Ed. to VET

Transfers from student visa subclass 573 to subclass 572

SVP

OVERVIEW

13

large and uncapped pool of temporary migrants with work entitlements on labour market

outcomes in Australia. More evidence in this area is needed for the purpose of informing

policies related to post-study work rights for both higher education and VET students.

Nonetheless, some barriers to graduate labour market entry are emerging as an issue for

international students. A recent study by Deakin University noted that many international

graduates are poorly prepared for the labour market and have unrealistic expectations of

graduate employment. The study pointed to the key role that universities can play in

enhancing the employment prospects of these students, and in conditioning their

expectations (either directly or through their agents).

Quality regulation is a ‘work in progress’

The quality and reputation of Australia’s education services rank highly as a determinant

of student demand. Reputation can be hard to gain but easy to lose. Australia has a specific

regulatory framework aimed at providing quality assurance and consumer protection for

education services supplied to international students. This complements the regulatory

framework that applies to the provision of domestic education services more generally.

Two national regulators were established in 2011 — the Tertiary Education Quality

Standards Agency (TEQSA) and the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA).

Further, changes to student visa policy settings (notably the delinking of the student visa

program from the pathway to permanent skilled migration since 2010) have removed some

of the systemic incentives for providers and students to behave in a manner inimical to the

provision of high quality IES in Australia.

Stakeholder concerns about the quality of IES appear to be mainly confined to some

segments of the VET sector — although there is an acknowledgment that quality issues in

one segment can have broader ramifications for the whole sector. Concerns about the VET

sector stems partly from experience (namely, the emergence of poor-quality providers in

the 2007–09 boom years) and partly from the very nature of the sector (relative to the

higher education sector) in terms of:

• the larger number of providers (around 500 registered to offer courses to international

students, compared with 133 in higher education)

• the prevalence of small scale operations

• the prevalence of relatively short duration courses compared with higher education

• lower barriers to entry and exit for providers.

Ongoing risks to the quality of education services offered by some VET providers remain.

Education providers’ compliance with regulations aimed at managing those risks has

improved in recent years as evidenced by the ratio of registration applications approved to

registration applications rejected rising materially. Providers also seem responsive to

regulatory intervention.

14

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

However, poor levels of compliance against some key standards remain (figure 5, and

chapter 4). In June 2014, ASQA reported that 33 per cent of all registered training

organisations were rated as having a medium or high risk of their not complying with the

relevant legislative obligations, with 11 per cent not yet having a risk rating assigned.

Comparable data for TEQSA are not published. Recent media reports have also

highlighted poor practices being used by some providers across both the higher education

and VET sectors (chapter 4).

Australian providers of offshore education services (transnational education) that do not

lead to Australian qualifications are outside the regulatory reach of TEQSA and ASQA.

Thus, these providers also pose a potentially significant risk to Australia’s reputation as a

quality provider of IES. ASQA has planned a strategic review of transnational VET

services in 2015.

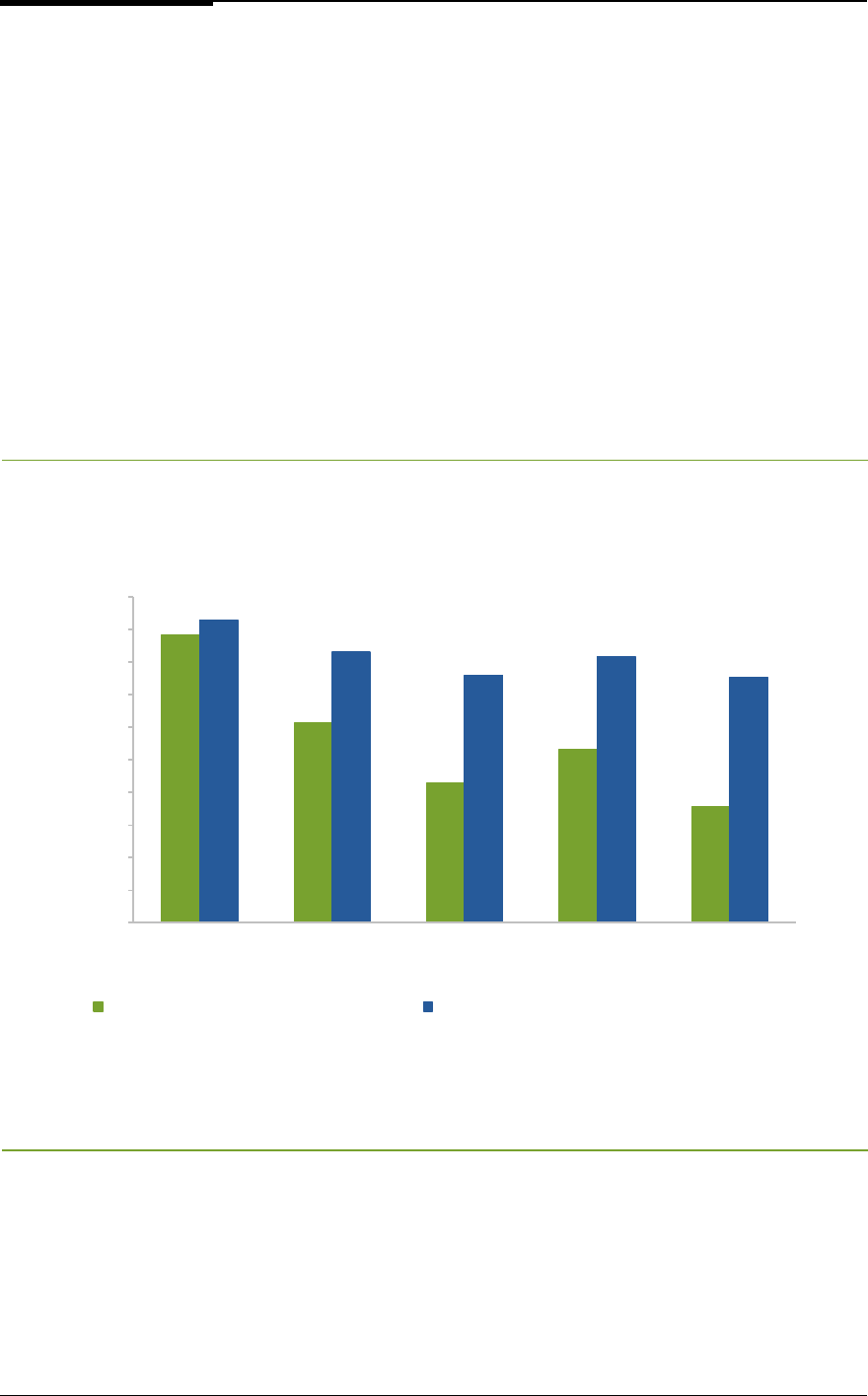

Figure 5 Compliance with standard 15

a

found at audits of providers

registered under CRICOS

b

to deliver VET

2013–14

a

S. 15.1 — Continuous improvement of training and assessment, S. 15.2 —

Training meets the

requirements of the training package, S. 15.3 — Required staff, facilities, equipment and material, S. 15.4

— Qualified and competent trainers and assessors, S. 15.5 — Assessment is undertaken properly.

b

Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students.

There has been a move to risk-based regulation

Since their inception, both ASQA and TEQSA have moved to a risk-based framework,

with resources targeted at areas that pose the greatest risk to quality. A pertinent question is

whether the Australian Government’s budget allocation to each agency is reflective of the

88

61

43

53

36

93

83

76

82

75

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 15.5

per cent

Standard

Providers compliant when audited Providers compliant following rectification

OVERVIEW

15

risks inherent in each segment. The Braithwaite Report noted that, in 2013-14, TEQSA

would have funding of over $117 000 for each provider it regulates on average, whereas

ASQA would have approximately $9500 for each provider on average.

The 2014-15 Federal Budget included a significant reweighting of funding for the two

national regulators. Future funding for TEQSA has been significantly reduced below its

2013-14 appropriation of around $24 million. Its funding for the three years from 2014-15

was reduced by around $21 million. In contrast, ASQA’s funding for those three years was

increased by around $68 million.

This raises a broader question about the sustainability and effectiveness of having two

national regulators over the medium term. The Commission sees merit in revisiting the

case for having one regulator for both the VET and the higher education sector, which

would allow an even stronger focus on risk-based regulation, help reduce the regulatory

burden (particularly for those institutions that offer both higher education and VET

courses), and provide a more consistent approach to quality regulation across the board.

A rebalancing from teaching to learning standards is called for

In order to be registered as a higher education provider or a training provider, organisations

must satisfy standards related to provider characteristics and governance, qualification,

information, and the quality of teaching and learning. Within the teaching and learning

standards category, the current quality assurance frameworks used by TEQSA and ASQA

are largely underpinned by compliance with input-based or teaching standards, such as the

quality of teaching and the availability of supporting infrastructure.

Such standards are valuable as leading indicators of quality. However, given that student

achievement is the ultimate goal of education, outcome-based or learning standards such as

the demonstration of generic and discipline-specific learning objectives (including

competency in the English language), are equally important from a quality assurance

perspective. This suggests that the current emphasis on teaching standards should be

rebalanced to provide for learning standards to have a greater role in quality assurance

arrangements.

That said, the Commission understands that both regulators already consider, to differing

extents, various outcome measures in their risk framework. As these measures are already

being collected and used, this suggests it could be a short step to formalise outcome

measures in the mandated standards against which providers are assessed for registration

and course accreditation purposes.

… as is better information to inform student choice

Information on courses for international students is available through various web portals

hosted by government agencies, individual institutions, industry bodies and education

agents.

16

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

While the regulatory regime imposes a requirement on providers to supply students with

information that will enable them to make informed decisions about their studies in

Australia, it does not require the national regulators to make public other information that

would assist students to make comparisons between providers.

ASQA and TEQSA already collect such information. Their auditing of providers’ against

registration and/or course accreditation standards generates information about relative

performance. At present, though, these audit results are not publicly available.

Equally, the current regulatory regime provides no publicly available information on the

relative quality of education services offered by providers, or measures of comparative

education outcomes such as completion rates or the distribution of levels of attainment for

students completing their studies.

Notwithstanding the challenges in measuring relative quality outcomes, the availability of

such information would offer greater transparency about the comparative ‘quality’ ranking

of providers and would benefit prospective students — both domestic and international. It

would help counteract misleading information provided to international students by

education agents. It may also strengthen the incentive for individual providers to improve

the quality of their education services.

Alternative frameworks for student visa processing

DIBP is currently undertaking a strategic evaluation of SVP arrangements and expects the

evaluation to play a key role in informing the policy guidelines that expire in mid-2016. As

part of its consultation informing the review, DIBP has proposed a revised model for

assessing immigration risk that would take into account the immigration risk outcomes of a

particular education provider (as is the case under the current system) and the immigration

risk applicable to the student’s country of citizenship (figure 6).

Such a model would have some advantages compared to the current model — it would

simplify the framework by having a single visa processing system applicable to all

education providers recruiting international students; and it would provide a more granular

approach to the management of immigration risks.

OVERVIEW

17

Figure 6 DIPB’s proposed framework for student visas

As always, implementation is the crux. How the proposed model is implemented will have

implications for the effectiveness of the student visa program. Principles of good

regulatory design would suggest that the proposed model should be clear and easy to

understand, proportionate to the risks posed, transparent and accountable.

Further, there are strong connections between international and domestic education

services. International education is also an established pathway to permanent migration.

An optimal student visa program cannot be designed in isolation from broader education

and immigration policy objectives. This calls for a coordinated approach to policy.

Indeed, it makes little sense for TEQSA or ASQA to be disciplining a provider while DIBP

is rewarding the same provider with a streamlined visa process under an immigration risk

framework.

Further, by focusing exclusively on immigration risk, the DIBP approach would do little to

address the perception among students and agents that an institution’s eligibility for SVP is

a marker of high education quality.

If the DIBP model is universally applied, all education providers with low immigration

risks, including VET providers, could potentially be granted access to SVP — and hence

be perceived as institutions of high quality education. Yet there are a number of low

quality providers. This presents a potential reputational risk to the international education

sector.

While there are high quality VET providers, the very nature of VET, with a much higher

churn rate of providers than in higher education, lends itself to relatively higher risks in

terms of educational quality compared to the higher education sector. This was one of the

reasons originally advanced by the Knight Review for limiting SVP to universities.

18

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

An expanded SVP program may also increase immigration risks, at least in the short-term.

This is because it could encompass a large number of new VET providers, some with little

or no experience in offshore student recruitment. In fact, the latter providers might initially

be advantaged by a system that is primarily focused on providers’ immigration risk history.

Two practical improvements to the DIBP proposal

One approach to mitigate the risks to perceptions of quality would be to build on the DIBP

proposed model by incorporating an additional dimension to capture education provider

quality risk — the risk that a provider would offer an international student a poor-quality

learning experience. Provider quality risk could draw on compliance ratings as already

assessed by the national regulators — TEQSA and ASQA — as an initial basis for

assessing education provider quality risk. This approach could involve the same

institutional settings currently used for the processing of student visas. However, it would

harness a broader range of evidence on which to base decisions on student visa grants.

Under this approach, each risk — country of citizenship immigration risk, education

provider immigration risk, and educational quality risk — would need to be assessed and

weighted to give an overall risk rating for each student visa applicant. Evidentiary

requirements for each risk rating should then be proportionate to the risks involved.

An alternative approach would seek to manage the systemic risks to quality that could

emerge from an extension of streamlined visa processing by making the quality of

education providers more explicit and transparent — as a way of breaking the nexus

between access to streamlined visa processing and perceptions of quality. This would

require TEQSA and ASQA to publish the quality risk ratings of individual providers and

for DIBP to more explicitly and credibly advertise that SVP is not a quality marker.

Perhaps this would involve a move away from terminology such as streamlined visa

processing.

The benefit of this approach is that it would quarantine immigration risks to one regulator

and one policy lever — DIBP through its visa settings and compliance framework, while

education quality risks would be managed through another policy lever by the education

regulators (TEQSA and ASQA) through their standards compliance regime.

Delineating responsibilities in this way could remove any misperceptions of educational

quality surrounding current arrangements. In relation to education quality it would leverage

off work already being done by TEQSA and ASQA, meaning that SVP requirements

would not add to the compliance and administrative costs for educational quality assurance

purposes.

Both approaches would require the DIBP and the Department of Education and Training to

have a high level of engagement to minimise the risk of policy coordination failure.

OVERVIEW

19

The Commission understands that the DIBP is developing its option further. The preferred

option should provide the highest net benefit to Australia as a whole.

The Commission’s ongoing inquiry into migration and its current study on barriers to

services exports will provide further opportunities to explore issues associated with student

visas.

The use of education agents is extensive and risky

Education agents can play a useful advisory and intermediary role for international

students and can be a cost-effective option for institutions looking to recruit students across

a range of countries (at least in the short-term).

Educational institutions in Australia use agents extensively for recruiting international

students, more so than in other comparable countries. Further, on average, Australian

institutions tend to pay higher commissions to agents relative to other countries, although

commissions paid by an institution are typically undisclosed. Commissions paid on a per

student basis on admission create incentives for agents to maximise the volume of

international students, with little regard to the quality of the advice provided to students

(affecting student expectations) or the quality and aptitude of the students.

The Commission received considerable anecdotal evidence that suggested unscrupulous

behaviour of agents is an issue, particularly in relation to providing false or misleading

advice and information, and the onshore poaching of international students. Many of these

concerns were also highlighted by the NSW Independent Commission Against Corruption

in its recent report.

In some cases, problems arise because there is a misalignment of incentives between

agents, providers and students. In other cases, incentives may be aligned, but providers,

agents and students may be acting against the interest of the Australian community more

broadly.

Agents are generally driven by their own profit motives (which are largely a function of

the quantity of students they recruit and the level of the course fees paid by students). They

are faced with inherent conflicts of interest because of the nature of their position — they

work on behalf of both education providers and students, and they also work for a range of

institutions in Australia and around the world. This is compounded by the limited ability of

education providers to observe the actions of their agents on the ground. This information

asymmetry, when combined with a misalignment of incentives, can lead to sub-optimal

outcomes.

Like several other countries, Australia does not regulate education agents directly. At a

national level, the National Code of Practice, established under the Education Services for

Overseas Students Act 2000 (Cwlth) sets out a range of specifications on the relationship

20

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

between providers and agents. At an institutional level, the risks are managed through their

relationships with agents.

The lack of a system for tracking agents and their clients’ outcomes, the lack of

transparency about provider-agent relationships, and the offshore location of many agents

make the oversight of the conduct of agents challenging. However, there are ways to

mitigate these risks, including through internalising the risk and reducing the reliance on

agents for recruitment through:

• a more direct recruitment approach by flagship Australian education institutions

targeted to the higher end of the value chain

• greater transparency around the relationships between agents and providers (including

the commissions paid)

• data systems that allow agent conduct and performance to be tracked over time

(including by tracking student outcomes over the longer term)

• the provision of training and information exchange programs.

Overall, excessive reliance on agents may lead to a less than optimal mix of international

students, with some of the best students enrolling in institutions in other countries such as

the US and the UK. While agents will remain an important part of the Australian

international education sector, there is scope for institutions to reduce their over-reliance

on agents and the potential to thus better target the best students from source countries.

This could be achieved by institutions investing more in the direct recruitment of students.

INTRODUCTION

21

1 Introduction

1.1 The international education sector’s contribution to

the economy

In 2014, Australian international education services (IES) delivered onshore (box 1.1)

contributed almost $17 billion to the Australian economy, or around 1 per cent of gross

domestic product. Of this, around half was made up of fees paid to education institutions,

with the remainder being expenditure on goods and services (figure 1.1, panel a). The

sector represented 27 per cent of services exports in 2014, and close to 5 per cent of total

Australian exports (in gross value terms as measured in Australia’s balance of payments).

In 2013-14, students enrolled in higher education (figure 1.2) provided the greatest

contribution to export income (68 per cent). Geographically, students studying in New

South Wales ($5.8 billion) and Victoria ($4.7 billion) generated the highest income for the

sector (figure 1.1, panel b).

International education also makes a significant contribution to employment in Australia

— both directly and indirectly. Deloitte Access Economics estimated that the expenditure

of international students generated jobs for just over 130 000 full time equivalent workers

in 2011 (DAE 2013). Further, international students add to the temporary labour pool in

Australia as they have work rights both while they study and post study.

At a micro level, IES provide a major source of revenue for Australia’s education

institutions (figure 1.1, panels c, d). In 2012, international students accounted for

16 per cent of the revenue of public universities on average (figure 1.1, panel c)

(TEQSA 2014b). However, the importance of international student fees for universities

varies, ranging from around 5 per cent of revenue for universities such as the University of

Notre Dame, the University of New England and Charles Darwin University to

20-30 per cent for universities such as RMIT University, Macquarie University, and the

University of Technology, Sydney (DET 2014b).

International student fees account for a smaller proportion of revenue for public vocational

education and training (VET) institutions (around 2.6 per cent), while limited data for

private VET make comparisons difficult. Around 82 per cent of commencements in higher

education in 2014 were at publicly-owned institutions, while the majority of

commencements in the VET and English language intensive courses for overseas students

(ELICOS) sectors were in private institutions (85 per cent and 78 per cent, respectively)

(figure 1.1, panel d).

22

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Box 1.1 International education services data

Data for offshore education services

Data limitations mean that it is difficult to determine the value of export services offshore.

Typically there are four modes of services export: mode 1 is cross border supply (for example

distance education provided to an offshore student); mode 2 is consumption in Australia (for

example, international students studying in Australia); mode 3 is a commercial presence in a

country of export (for example, an offshore campus of an Australian university); and mode 4 is

the presence of natural persons in a country of export (for example, an Australian educator

travels to deliver an education service abroad but returns to Australia within a 12 month period).

In general services exports provided through mode 3 are not included in balance of payments

estimates and, moreover, there are limited data on exports through commercial presence

(PC 2015a). This means that modes 1 and 4 are only partial estimates of the value of education

export income derived from offshore services. Accordingly, where it is mentioned in this study,

export values are based on the mode 2 definition.

Types of IES data

A range of data is collected to measure international education services. Each data set

measures different aspects of IES (though sometimes overlapping), and therefore needs to be

placed in context.

Enrolment data — counts a student enrolment in a course. A student enrolled in two different

courses is counted as two enrolments. As a result, enrolment data generally do not represent

the number of overseas students in Australia or the number of student visas issued, but rather,

counts actual course enrolments. Enrolment data overstate the number of international students

in Australia.

Commencement data — counted as a new student enrolment in a particular course at a

particular institution. Commencement figures show the flow of international students in

Australia.

Visa applications lodged — the number of applications received by the Department of

Immigration and Border Protection (both in hard copy and electronically).

Student visas granted — the number of visas where the decision maker assesses the

application and decides to award the visa. It usually includes primary visa holders (the student)

and secondary visa holders (those who have satisfied a secondary criteria for the grant of a

visa, generally dependants of the primary visa holder).

Student visa holders in Australia — the number of student visa holders in Australia at a

particular point in time. Some student visa holders may not be in Australia at the time of the

snapshot.

ELICOS data — most data for ELICOS are confined to those ELICOS students in Australia on a

student visa (chapter 2, box 2.1).

Education institutions — particularly universities — state that revenue from international

students allows institutions to expand their staff, increase funding for research and enhance

their investment in infrastructure (Go8 2014b). Further, it enables them to enhance the

quality and diversity of the courses that they provide, take advantage of scale economies

INTRODUCTION

23

and diversify their funding base (provided they also make sufficient infrastructure and

other investments to provide a quality learning environment for international students).

Figure 1.1 The significance of international education services

a

a. International student expenditure by sector

2013-14

b

b. Division of income from IES by jurisdiction,

2013-14

c. Sources of university revenue, 2012 d. International student commencements by

provider ownership type, 2014

a

Data are for onshore international education services only.

b

Expenditure by those on a student visa.

Sources: ABS (International Trade in Services by Country, by State and by Detailed Services Category,

Calendar Year, 2013 Cat. no. 5368.0.55.004); Deloitte Access Economics (2011); NCVER (2014b).

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

$ billions

Expenditure on fees

Expenditure on goods and services

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

per cent

NSW Vic Qld

WA SA ACT

Tas and NT

0

50

100

per cent

Other

State and territory governments

Consultancies

Investment and royalty income

Australian Government

Domestic fee paying students

Domestic HELP

International student fees

0

20,000

40,000

60,000

80,000

100,000

120,000

Public Private

24

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Figure 1.2 Levels of education

While it is not the intention of this report to quantify the net benefits of international

education exports, the economic literature has generally found that international students

bring broader benefits. For example, international students — and particularly postgraduate

students — have been found to have positive impacts for innovative activity in the

economy (Chellaraj, Maskus and Mattoo 2008; Stuen, Mobarak and Maskus 2012).

Further, international students make a significant contribution to Australian society,

diversifying and enriching communities, strengthening Australia’s global networks and

facilitating future research collaboration (ABS 2011).

1.2 Snapshot of the international education services

sector

The sector is large and diverse

The IES sector is characterised by a complex network of institutions, government agencies,

regulatory frameworks and other participants (figure 1.3).

Bachelor’s Degree

Doctoral Degree

Master’s Degree

Bachelor’s Honours Degree,

Graduate Certificate,

Graduate Diploma

Advanced Diploma, Associate

Degree

Diploma

Certificate IV

Certificate III

Certificate II

Certificate I

Post-

graduate

study

Vocational

Education

and

Training

(VET)

Tertiary

education

Higher

education

School system (including

kindergarten, primary school,

high school)

English language courses for

overseas students (ELICOS)

Courses within the Australian Qualifications Framework (AQF)

Outside the

AQF

Course levels Education services terminology

INTRODUCTION

25

Figure 1.3 Policy and regulatory landscape for international education

services

The services undertaken as part of the sector — while focused on education — are broad

and interconnected. Education is provided at a range of levels, in varied locations, through

both public and private providers. It ranges from school level (primary and high school),

through to ELICOS, VET and higher education both by coursework and research

(figure 1.2; figure 1.4, panel a). Providers deliver courses to international students across a

wide field of education sectors (table 1.1).

In 2014 there were just over 450 000 international students in Australia (DET 2015c). The

number of total enrolments was higher at around 590 000 enrolments — reflecting that

some students are enrolled in several courses concurrently (box 1.1; figure 1.4, panel b).

About 5 per cent of all VET students are international students and around one fifth of all

higher education students are international students (chapter 2).

Australian Skills Quality Authority

(ASQA)

Tertiary Education Quality

Standards Agency

(TEQSA)

Education Services for

Overseas Students Act

2000 (Cwlth

)

National Code of Practice for Registration

Authorities and Providers of Education and

Training to Overseas Students 2007

Commonwealth Register of Institutions and Courses for Overseas Students (CRICOS)

Higher education

+ foundation courses

+ ELICOS delivered by a registered

higher education provider or under an

entry arrangement with a higher

education provider

VET

providers

ELICOS providers

(except when

delivered by a school

or higher education

provider)

Schools

+ ELICOS and

foundation programs

when delivered in a

school

Students

Relevant state

or territory

regulators

Legislation and

regulation specific

to IES

Registration

requirements

Regulators

Service providers

Purchasers

Education agents

Policy oversight

Department of

Education and

Training

(IES policy

development)

Department of

Immigration and

Border

Protection

(visa settings)

AusTrade

(marketing

and

promotion)

State and

territory

government

departments

Migration Regulations

1994

Department of

Employment

(labour market

outcomes)

26

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Table 1.1 Number of courses and number of providers registered to

deliver to international students by field of education

a

Field of education

Courses Providers

Number Per cent Number Per cent

Management and commerce

3 169

22.9

317

16.1

Society and culture

2 930

21.1

347

17.6

Engineering and related technologies

1 184

8.5

114

5.8

Health

1 065

7.7

111

5.6

Mixed field programs

1 070

7.7

453

22.9

Creative arts

899

6.5

120

6.1

Information technology

849

6.1

131

6.6

Natural and physical sciences

801 5.8 58 2.9

Food, hospitality and personal services

738

5.3

133

6.7

Education

480

3.5

86

4.4

Architecture and building

344

2.5

55

2.8

Agriculture, environmental and related studies

328

2.4

49

2.5

Total

13 857

100.0

1 974

100.0

a

Data as at February 2015.

Source: Department of Education and Training data 2015.

In 2014, the largest sub-sector for student enrolments was higher education (45 per cent of

total international student enrolments), with VET the second largest sub-sector (25 per cent

of enrolments) (figure 1.4, panel b). Of higher education international students, 81 per cent

commenced with public providers, while only 15 per cent of VET international student

commencements were with public providers (Austrade 2014b). The largest source country

for international students was China, with 26 per cent of all international student

enrolments in Australia, followed by India, with 11 per cent of total international student

enrolments (figure 1.4, panel c) (DET 2014c).

Transnational education may be delivered by an Australian institution based offshore or

through a collaboration or partnership with local education providers. Offshore education

currently represents just over one quarter of international education enrolments (figure 1.4,

panel d).

The digital economy is also broadening the options available to those seeking an education

with an international orientation. Technological advances have enabled the growth of

‘massive open online courses’ (MOOCS), as well as a wider range of teaching and study

modes. The number and availability of MOOCs continues to grow but has so far not

detracted from growth in traditional delivery modes.

2

2

MOOC providers include Khan Academy and Coursera, for example.

INTRODUCTION

27

Figure 1.4 Profile of international education services

a. Number of international education providers, 2014

a

b. Number of students enrolled by sector, 2014

c. Student enrolment by source country, 2014

d. Student enrolments onshore and offshore, 2013

b

a

The diagram does not include around 70 providers in the higher education, VET, ELICOS and schools

sectors that also offer ‘other’ courses. ‘Other’ courses are non-award courses such as foundation/entry

requirement courses or study abroad courses.

b

Total offshore enrolments excludes distance education and

private VET providers (for which accurate data are unavailable).

Sources: DET (2014c, 2014i); data from the Department of Education and Training.

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

700

Thousands

Higher Education VET

Schools ELICOS

Non-award

0

40

80

120

160

Thousands

Higher Education VET

Schools ELICOS

Non-award

0

100

200

300

400

500

600

Total onshore IES

enrolments

Total offshore

enrolments

Thousands

28

INTERNATIONAL EDUCAT

ION SERVICES

Supporting the services provided by education institutions are other participants in the

sector, such as education agents. Education agents identify prospective students for

Australian institutions based in Australia and in competing countries, provide students with

information about lifestyle, courses and education providers, assist students with enrolment

and visa applications, and sometimes collect course fees on a provider’s behalf (chapter 6).

Governance and promotion is through a range of organisations

A range of government agencies and regulators at different levels of government are

involved in the international education sector, reflecting the Council of Australian

Government’s view that ‘all governments are responsible for the international student

experience’ (COAG 2014, p. 2).

The Education Services for Overseas Students Act 2000 (Cwlth) (ESOS Act) is the main

legislation governing the sector and is designed to protect the interests of student visa

holders. Australian Government agencies take a lead role in areas such as IES policy

development (Department of Education and Training), visa policy settings (Department of

Immigration and Border Protection), work opportunities (Department of Employment) and

marketing the Australian brand (Austrade, through its Future Unlimited Study in Australia

portal).

There are two national regulators of quality for the delivery of IES in the higher education,

VET and ELICOS sectors

3

— the Tertiary Education Quality and Standards Agency

(TEQSA) and the Australian Skills Quality Authority (ASQA) (figure 1.3, chapter 4).

State and territory governments are intrinsically linked to the system, particularly as they

fund and have ownership of many education institutions that teach international students.

State or territory regulatory bodies remain responsible for the oversight of international

students enrolled in schools. State and territory bodies (such as StudyNSW and Study

Perth) market international education opportunities in their respective jurisdictions.

1.3 International education policy levers

Government involvement in international education

Government involvement in the IES sector is more ubiquitous than in many other sectors.

This occurs for a number of reasons. Government itself is involved in the delivery of these

services through the ownership of public education institutions.

3

In the VET sector, ASQA is the national regulator for all IES provided across Australia. For VET service

providers that do not deliver IES, Victoria and Western Australia retain their own regulatory authorities,

with ASQA regulating the rest of the country.

INTRODUCTION

29

More broadly, there are inherent features of that market that prevent it from operating

efficiently without government intervention. These include the information asymmetries

between providers and students, which prevent students from fully assessing the value of

the education service they are purchasing, and the scope for poor quality providers to taint

the reputation of all providers and/or adversely affect the perceived quality of Australian

qualifications.

Further, the flow of international students into Australia is of necessity subject to

immigration policy settings. The temporary migration and work rights afforded by

international education (via student visas) directly affects its attractiveness. Hence,

immigration policy directly affects the demand for international education services.

Further, while the supply of international education is an export business, the provision of

education to international students is largely a joint product with the provision of education

to domestic students (Johnston, Baker and Creedy 1997); indeed, many institutions

purportedly use international student fees to cross-subsidise other activities such as

research. To this extent, student visa policy settings can affect the financial viability of

domestic education (more so in some segments than others) and can also affect (positively

or negatively) the value of the qualifications of domestic students.

International education is also a pathway to permanent migration. While student visa

policy settings should be set to achieve the desired short- and long-term immigration mix,

governments can come under pressure from the international education sector to take their

businesses into account. However, it is not the role of government to ensure a reliable

supply of international students for the sector. Rather, an important role of government is

to provide a stable and predictable policy and regulatory framework that supports

behavioural responses by education providers, international students and other players that

are consistent with broader immigration and education policy objectives, while enabling

the market for IES to function efficiently and effectively within these objectives.

More generally, policies related to domestic education, notably in regard to quality, will

spill over into the international education sector. The cost and quality of education services

are key considerations for most students when choosing an international education